If you ask British birdwatchers to name the eleven wader species that are causing the most conservation concern in the UK, they would probably not include Dunlin. Curlew may well be top of their lists, even though the most recent population estimate is 58,500 breeding pairs, but would people remember to include Ruff?

This blog is a new incarnation of Nine Red-listed UK Waders, explaining why there are now eleven shorebird species on the UK Red List. Its publication coincides with the appearance of the BTO book Into the Red which highlights the problems being faced by seventy species that breed and/or spend the winter in the United Kingdom. The work of seventy writers and seventy artists has been curated by Kit Jewitt (@YOLOBirder on Twitter) and Mike Toms (BTO), and the book is being sold to support the work of both the BTO and the Rare Breeding Birds Panel.

What’s a Red List?

The UK Red List is made up of a strange mixture of common and rare species. Nobody will be surprised to see fast-disappearing Turtle Dove and Willow Tit, but why are 5.3 million pairs of House Sparrow (right) in the same company?

The list is very important because it helps to set the agenda for conservation action, influences the way that money for research is distributed and focuses attention during planning decisions. The main criteria for inclusion are population size – hence the inclusion of species that are just hanging on in the UK, such as Turtle Dove – and the speed of decline of common species. Data collected by volunteers, working under the auspices of the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), measured a population decline for House Sparrow of 69% between 1977 and 2018, which is worrying enough to earn this third most numerous breeding species in the UK a place in Into the Red.

Mark Eaton of the Rare Breeding Birds Panel explains how listing works.

The Birds of Conservation Concern (BOCC) system, through which the Red List and Amber Lists are determined, uses a strict set of quantitative criteria to examine the status of all of the UK’s ‘regularly’ occurring species (scarce migrants and vagrants aren’t considered), and uses a simple traffic light system to classify them. There are ‘Red’ criteria with thresholds for rates of decline in numbers and range, historical decline and international threat (if a species is considered globally threatened it is automatically Red-listed in the UK), together with a range of other considerations such as rarity, the international importance of UK populations, and how localised a species is. If a species meets any of the Red List criteria it goes onto the Red List.

This blog is about the eleven waders in Into the Red, but there are 59 other fascinating species accounts and wonderful artworks. Each of the species accounts below starts with a quote from the book and is accompanied by a low-resolution version of the artwork.

Dotterel

“Dot, dot, dot, Dotterel. Disappearing – a dash, dashing off the page.” – Alicia Hayden

The UK’s small population of Dotterel is restricted to the high tops of Scottish mountains, with only occasional breeding reports elsewhere. Three decades ago, the warning bells were raised, as warming conditions and an elevated snowline turned the Dotterel into a poster bird for climate change campaigners. The detailed reasons for the species’ decline may still need to be nailed down but candidate causes, such as declining insect food supplies and the increasing numbers of generalist predators, are probably all linked to a changing climate – squeezing Dotterel into a smaller area of the mountain plateaux of Scotland.

There’s a blog about the decline in Dotterel numbers called UK Dotterel numbers have fallen by 57%, based upon a paper that uses data up until 2011. At this point, the population was estimated at between 280 and 645 pairs. There has been no suggestion of improvement since that blog was written. Interestingly, Dotterel may have a way out of their predicament, as we know that marked individuals move between Scotland and Norway in the same breeding season. See also Scotland’s Dotterel: still hanging on, which highlights the pressures that youngsters face in North Africa, during the first eighteen months of their lives.

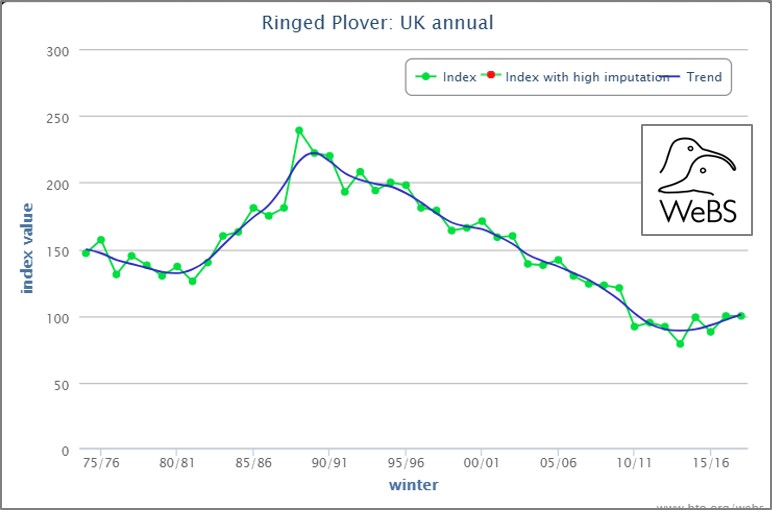

Ringed Plover

“The gentle scuttle over the rocks, the unmistakable bum-bob and the elegant glide into a nest site” – Dan Rouse

One of the criteria that the BOCC panel takes into account, when constructing the Red List, is the responsibility the UK has for a species or subspecies in the breeding season, during winter or both. The Ringed Plovers we see in the UK in the winter are almost exclusively of the hiaticula subspecies; birds that breed in southern Scandinavia, around the Baltic, in western Europe and in the UK. There are only estimated to be 73,000 individuals in this subspecies, so the 42,500 that winter in the UK constitute a large percentage of the Ringed Plovers that breed in many of these countries.

The Wetland Bird Survey graph shows a decline of over 50% between 1989 and 2014. At the start of the period, Ringed Plover numbers were at an all-time high but this is still a dramatic and consistent drop. Numbers on the open coast did not drop as much (see Waders on the coast) and those on estuaries may have stabilised or even have increased slightly, since 2014, but Ringed Plovers need some good breeding years. Disturbance is an issue for nesting Ringed Plovers, which share their beaches with visitors and dogs, as discussed in this blog about the ‘no go’ areas along the Norfolk and Suffolk coasts – On the beach. Winter disturbance can be a problem for waders too (see Disturbed Turnstones).

Lapwing

“I heard them before I saw them. Like the plaintive squeak of a rubber toy, or an oboist tuning up …” – Tessa Boase

The Lapwing used to nest across the whole of the United Kingdom and was a common bird in almost every village. It’s still the most numerous breeding wader in the UK, with 97,500 pairs (APEP4), beating Oystercatcher by just 2,000 pairs. Numbers dropped by 55% between 1967 and 2018, according to BirdTrends 2020, published by BTO & JNCC. Huge losses had already occurred over the previous two centuries, as land was drained and vast numbers of eggs were collected for the table. The Lapwing is now a bird associated with lowland wet grasslands and the uplands, rather than general farmland.

Red-listing has been important for Lapwing, increasing the profile of the species and encouraging the development of specific agri-environment schemes targeted at species recovery. These include ‘Lapwing plots’ in arable fields and funding to raise the summer water tables in lowland grassland. Several WaderTales blogs describe efforts to try to increase the number of breeding waders in wet grassland, especially Toolkit for Wader Conservation. The loss of waders, and Lapwings in particular, from general farmland is exemplified in 25 years of wader declines. There are many predators that line up to take Lapwing eggs so it pays to nest in loose ‘colonies’, so that guard duties can be shared.

Whimbrel

“Whimbrel have been doing this journey, between tundra and heath of northern Europe to mudflats and mangroves of Africa, for at least 1.9 million years” – Rosie Ellis

Most British and Irish birdwatchers think of Whimbrel as spring migrants, enjoying seeing flocks of Icelandic birds when they pause on their way north from West Africa (see Iceland to Africa non-stop). There is a small, vulnerable UK population nesting almost exclusively on Shetland. The latest estimate is 290 pairs (2009), down from an estimate of 530 pairs, published in 1997. We await the results of a 2021 survey with interest. Many pairs have been lost from Unst and Fetlar and this blog about habitat requirements might give clues as to why: Establishing breeding requirements of Whimbrel.

The curlew family is in trouble across the Globe, potentially because these big birds need so much space (see Why are we losing our large waders?). Hints of future issues for Eurasian Whimbrel are coming from Iceland, where forestry is squeezing them out of some key areas: Iceland’s waders need a strategic forestry plan.

Curlew

“A song that seems to split in mid-air and take the heart in two directions at once” – David Gray

What more can be said about Curlew, ‘promoted’ to the red list in 2015 and designated as ‘near threatened’ globally. Most significant is the story from Ireland, where 94% of breeding birds disappeared in just 30 years. These blogs provide more information about the decline and review some of the reasons.

- Is the Curlew really near-threatened?

- Curlews can’s wait for a treatment plan

- Ireland’s Curlew Crisis

- More Curlew chicks needed

Across every part of the UK, stakeholder groups have come together to support populations of breeding Curlew, using a mixture of habitat management, predator reduction and nest protection measures. One recent innovation is to raise chicks in captivity, in an attempt to boost local populations in England. There’s more in Will head-starting work for Curlew?

Black-tailed Godwit

“These birds become old friends and open our eyes to the world of migration” – Jennifer Gill

Winter Black-tailed Godwit numbers are booming but these are islandica – birds that have benefited from warmer spring and summer conditions in Iceland, as you can read here in: From local warming to range expansion. Their limosa cousins are in trouble in their Dutch heartlands (with declines of 75%) and there have been similar pressures on the tiny remaining breeding populations in the Ouse and Nene Washes, as you can discover in England’s Black-tailed Godwits. A head-starting project in the Washes is boosting the number of chicks; so much so that released birds now make up more than a quarter of this fragile population. Red-listing has shone a spotlight on this threatened subspecies, attracting the funding needed for intensive conservation action.

Ruff

“But then, good grief, in May and June, I’m treated to a different plume; A glorious crown, I gush and swoon – and then, no doubt, I change my tune.” – Jess French

Some Ruff spend the winter months in the UK and numbers are boosted in spring as birds pass through on their way from Africa to Scandinavia and the Baltic countries. Occasionally, males in glorious breeding attire will display in leks, perhaps attracting the attention of females. As a (very) scarce breeder, Ruff automatically earns a place on the Red List.

250 years ago, Ruff were breeding between Northumberland and Essex, before our ancestors learnt how to drain wetlands and define a hard border between the North Sea and farmland. Hat-makers, taxidermists and egg-collectors added to the species’ woes and, by 1900, breeding had ceased. The 1960s saw a recolonisation and breeding Ruff are still hanging on. Lekking males cause excitement in sites as disparate as Lancashire, Cambridgeshire and Orkney, and there are occasional nesting attempts. Habitat developments designed to help other wader species may support Ruff but the situation in The Netherlands does not suggest much of a future. Here, a once-common breeding species has declined to an estimated population of 15 to 30 pairs (Meadow birds in The Netherlands).

Dunlin

“Memories of sunny days, swirling flocks of waders and blisters from closing metal rings still linger. How can a bird that was so numerous less than 50 years ago now be Red-listed?” – Graham Appleton

There are good reasons for the addition of Dunlin to the UK Red List; breeding numbers of the schinzii race have declined significantly and the number of wintering alpina Dunlin in Great Britain dropped 10,000 between two periods that were only eight years apart, as you can read in this blog about population estimates for waders.

The fall in breeding numbers is probably the bigger problem, as indicated by range reductions in successive breeding atlas periods (1968-72, 1988-91 and 2008-11). It’s hard to monitor what is happening to numbers on a year-by-year basis because the breeding distribution is too patchy and thin to be picked up via the Breeding Bird Survey. Alarm bells are being raised in Ireland, where numbers have dropped to between 20 and 50 pairs (Status of Rare Breeding Birds across the island of Ireland, 2013-2018), and in the Baltic, where numbers have fallen by 80% since the 1980s. There’s a WaderTales blog about Finnish Dunlin.

The winter decline in the UK may or not be an issue, although it has to be considered as part of large-scale moderate losses across the whole of western Europe. There is a theory that, over the years, as winter conditions on the continental side of the North Sea have become less harsh, new generations of juvenile alpina have settled in countries such as the Netherlands, instead of continuing their southwesterly migrations from northern Russia. Once a wintering site has been chosen, individuals are site faithful, so one ends up with newer generations on the continent and ageing adults in the UK and Ireland. WeBS counts for Dunlin are half what they were 25 years ago.

Purple Sandpiper

“It’s an easy species to overlook, the Purple Sandpiper. For a start, they’re not purple” – Mark Eaton

Purple Sandpiper earns its red listing because a very small number of pairs nest in Scotland. Proof of successful breeding is rare and the species may drop off the list at the next review, as Temminck’s Stint did in 2015. Extirpated species (birds that no longer breed) are not red-listed.

In winter, the rocky coasts of the UK are home to Purple Sandpipers from the Arctic, with a suggestion that North Sea coasts, south of Aberdeen, mainly play host to birds from Spitsbergen and northern Scandinavia, with Greenlandic and Canadian birds more likely to be found further north and on the Atlantic coast. Coastal numbers declined by 19% between 1997/98 and 2015/16, according to the Non-estuarine Waterbird Survey, and WeBS counts suggest numbers have at least halved over a period of 25 years. The Highland Ringing Group has shown that the number of young Purple Sandpipers has been declining on the Moray Firth, suggesting several years with relatively poor breeding success, for birds migrating from the northwest, or short-stopping by new generations of youngsters, as discussed for Dunlin. Perhaps they are wintering in Iceland these days?

Woodcock

“Like clockwork, I’d encounter this sight at 7 pm each summer evening as one flew over my head in the back garden, heading towards the thick woodland.” – Megan McCubbin

The presence of Woodcock on the Red List causes heated debate; how can this still be a game species? Red-listing is indisputable; the most recent survey by BTO & GWCT showed that there was a decline in roding males from 78,000 in 2003 to 55,000 in 2013, with the species being lost from yet more areas of the UK. Each autumn, the number of Woodcock in the UK rises massively, with an influx of up to 1.4 million birds. Annual numbers depend upon seasonal productivity and conditions on the other side of the North Sea. A recent report on breeding wader numbers in Norway, Sweden and Finland, shows that breeding populations of Woodcock in this area are not declining (Fennoscandian wader factory).

The UK’s breeding Woodcock population is under severe threat from things such as increased deer browsing and drier ground conditions but winter numbers appear to be stable. The difference in conservation status between breeding and wintering populations is reflected in the fact that Woodcock is on both the Red List and the Quarry List, for now. There is a WaderTales blog (Conserving British-breeding Woodcock) that discusses ways to minimizes hunting effects on British birds. These guidelines from GWCT emphasise the importance of reducing pressures on British birds.

Red-necked Phalarope

“The evening light was beautiful, and it was just amazing to watch it spinning around in characteristic fashion” – Dawn Balmer

Red-necked Phalaropes that breed in Shetland and a few other parts of northern Scotland appear to be an overflow from the Icelandic population; birds which migrate southwest to North America and on to the Pacific coastal waters of South America. This BOU blog describes the first track revealed using a geolocator.

The Red-necked Phalarope was never a common breeder and came under pressure from egg-collectors in the 19th Century. Numbers are thought to have recovered to reach about 100 pairs in Britain & Ireland by 1920. Numbers then fell to about 20 pairs by 1990, so the latest estimate of 108 pairs in 2018 reflects conservation success (The Rare Breeding Birds Panel). Given the restricted breeding range and historical declines, it is unlikely that the next review will change the conservation status from Red to Amber, despite the recovery of numbers.

In conclusion

The Red List creates some strange bedfellows. In the book, Turtle Dove follows Herring Gull (right); a bird with links to love and romance and another with at best the charm of a roguish pirate. But the List works; it creates an evidence-base that help those who devise agricultural subsidy systems, advise on planning applications, license bird control and prioritise conservation initiatives.

Into the Red aims to raise awareness of the UK’s most at-risk bird species, eleven of which are waders, and to raise money to support the Rare Breeding Birds Panel and BTO research scientists. This is a follow-up to Red67, published in 2019 and based on the Red List from 2015. It is sad that this version covers 70 species, rather than 67. Worryingly, the first Red List, produced in 1990, only had 36 species on it.

Into the Red is a lovely book that captures the thoughts and images of a generation. Details of how you can order a copy from the BTO can be found here.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton (@GrahamFAppleton) to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on published papers, with the aim of making shorebird science available to a broader audience.

THIS BLOG HAS BEEN UPDATED

THIS BLOG HAS BEEN UPDATED In his foreword to Red67, Mark Eaton, Principal Conservation Scientist for RSPB, explains how listing works. The Birds of Conservation Concern (BOCC) system, through which the Red List and Amber List are determined, uses a strict set of quantitative criteria to examine the status of all of the UK’s ‘regularly’ occurring species (scarce migrants and vagrants aren’t considered), and uses a simple traffic light system to classify them. There are ‘Red’ criteria with thresholds for rates of decline in numbers and range, historical decline and international threat (if a species is considered globally threatened it is automatically Red-listed in the UK), together with a range of other considerations such as rarity, international importance of UK populations, and how localised a species is. If a species meets any of the Red List criteria it goes onto the Red List.

In his foreword to Red67, Mark Eaton, Principal Conservation Scientist for RSPB, explains how listing works. The Birds of Conservation Concern (BOCC) system, through which the Red List and Amber List are determined, uses a strict set of quantitative criteria to examine the status of all of the UK’s ‘regularly’ occurring species (scarce migrants and vagrants aren’t considered), and uses a simple traffic light system to classify them. There are ‘Red’ criteria with thresholds for rates of decline in numbers and range, historical decline and international threat (if a species is considered globally threatened it is automatically Red-listed in the UK), together with a range of other considerations such as rarity, international importance of UK populations, and how localised a species is. If a species meets any of the Red List criteria it goes onto the Red List.  “It’s the crest that does it for me – that flicked nib stroke, the artist’s afterthought” – Lev Parikian

“It’s the crest that does it for me – that flicked nib stroke, the artist’s afterthought” – Lev Parikian “They gather at high tide like shoppers waiting for a bus: all facing the same direction, and all staring into the distance” – Stephen Moss

“They gather at high tide like shoppers waiting for a bus: all facing the same direction, and all staring into the distance” – Stephen Moss “I want you in the mountains. Summer breeze. At home. Doing your thing. So don’t go disappearing on us, okay?” – Fyfe Dangerfield

“I want you in the mountains. Summer breeze. At home. Doing your thing. So don’t go disappearing on us, okay?” – Fyfe Dangerfield “How often do Whimbrels pass overhead nowadays? Unseen and unheard, their calls mean nothing to most of us” – Patrick Barkham

“How often do Whimbrels pass overhead nowadays? Unseen and unheard, their calls mean nothing to most of us” – Patrick Barkham “… achingly vulnerable in a world that is battling to hold onto loveliness” – Mary Colwell

“… achingly vulnerable in a world that is battling to hold onto loveliness” – Mary Colwell “A glimpse of terracotta is obscured by ripples of grass, dipping gently in the breeze” – Hannah Ward

“A glimpse of terracotta is obscured by ripples of grass, dipping gently in the breeze” – Hannah Ward “They look a bit inelegant – a small head for a decently sized bird, a halting gait, and that oddly vacant face” – Andy Clements

“They look a bit inelegant – a small head for a decently sized bird, a halting gait, and that oddly vacant face” – Andy Clements “… snatching flies from the water in fast, jerky movements, droplets dripping from its slender beak” – Rob Yarham

“… snatching flies from the water in fast, jerky movements, droplets dripping from its slender beak” – Rob Yarham “… taking the earth’s temperature with the precision of a slow, sewing-machine needle” – Nicola Chester

“… taking the earth’s temperature with the precision of a slow, sewing-machine needle” – Nicola Chester Graham (

Graham (

As a volunteer taking part in the Breeding Bird Survey (BTO/JNCC/RSPB) in the UK, I feel that I do my bit to monitor what is happening to local bird population – providing counts that build into national trends. The work involved in delivering indices for breeding waders across the area of Fennoscandia shown in the map is in a different league. Here, counters visit habitats as diverse as forests, wetlands, mires and tundra, within the boreal and arctic areas of Norway, Sweden and Finland. Some survey sites are so remote that access requires the use of helicopters.

As a volunteer taking part in the Breeding Bird Survey (BTO/JNCC/RSPB) in the UK, I feel that I do my bit to monitor what is happening to local bird population – providing counts that build into national trends. The work involved in delivering indices for breeding waders across the area of Fennoscandia shown in the map is in a different league. Here, counters visit habitats as diverse as forests, wetlands, mires and tundra, within the boreal and arctic areas of Norway, Sweden and Finland. Some survey sites are so remote that access requires the use of helicopters.

Looking at the results from across Norway, Sweden & Finland:

Looking at the results from across Norway, Sweden & Finland:

Lapwing. The trends within the three Fennoscandian countries are very different. In Norway, there has been a dramatic decline (-15.2% per year during 2006–2018) and the Lapwing is now nearly extinct in many areas. The trend in Sweden is also significantly negative (-5.8% per year). In Finland, however, where the species is more widespread and numerous, there has been a strong increase (+5.9% per year) during the same period. See figure alongside.

Lapwing. The trends within the three Fennoscandian countries are very different. In Norway, there has been a dramatic decline (-15.2% per year during 2006–2018) and the Lapwing is now nearly extinct in many areas. The trend in Sweden is also significantly negative (-5.8% per year). In Finland, however, where the species is more widespread and numerous, there has been a strong increase (+5.9% per year) during the same period. See figure alongside.

Ruff. There were major declines in the period immediately prior to this review (

Ruff. There were major declines in the period immediately prior to this review (

How many waders spend the winter in Great Britain? The answer is provided within an article in British Birds entitled

How many waders spend the winter in Great Britain? The answer is provided within an article in British Birds entitled  Population totals help to put annual percentage changes into context;

Population totals help to put annual percentage changes into context; For species of wader that also make use of the open coast, the Non-estuarine Waterbirds Survey of 2015/16 (or NEWS III) provided additional data, updating the NEWS II figures from 2006/07.

For species of wader that also make use of the open coast, the Non-estuarine Waterbirds Survey of 2015/16 (or NEWS III) provided additional data, updating the NEWS II figures from 2006/07. Great Britain is extremely important in the context of the East Atlantic Flyway, as is obvious from the fact that the area holds nearly five million waders. The WeBs counts already monitor the ups and downs on an annual basis but this review provides an opportunity to turn the percentages into actual numbers. It is concerning that, over a period representing less than a decade, the average maximum winter count for six of the species that were surveyed dropped by a total of over 150,000. These big losers were Knot, Oystercatcher, Redshank, Curlew, Grey Plover and Dunlin, ordered by number of birds lost, with Knot seeing the biggest absolute decline.

Great Britain is extremely important in the context of the East Atlantic Flyway, as is obvious from the fact that the area holds nearly five million waders. The WeBs counts already monitor the ups and downs on an annual basis but this review provides an opportunity to turn the percentages into actual numbers. It is concerning that, over a period representing less than a decade, the average maximum winter count for six of the species that were surveyed dropped by a total of over 150,000. These big losers were Knot, Oystercatcher, Redshank, Curlew, Grey Plover and Dunlin, ordered by number of birds lost, with Knot seeing the biggest absolute decline.

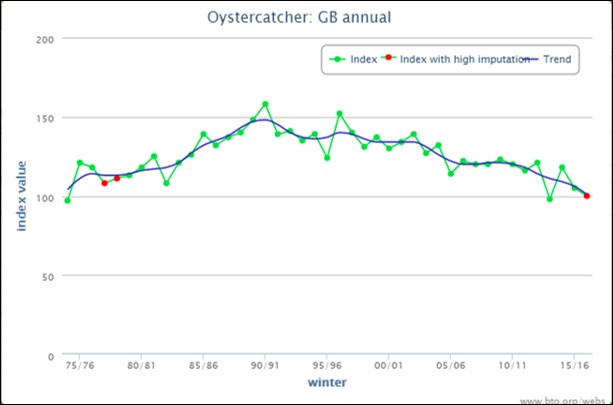

The drop in Oystercatcher numbers from 320,000 to 290,000 appears to be less than 10%, compared to a ten-year decline of 12% on WeBS. Improved analysis of NEWS data helped to add some more birds to the open-coast estimate so the 10% fall may underestimate the seriousness of the Oystercatcher situation. The 25-year Oystercatcher decline on WeBS is 26%, which is not surprising if you look at the changes to breeding numbers in Scotland, where most British birds are to be found. There’s more about this in:

The drop in Oystercatcher numbers from 320,000 to 290,000 appears to be less than 10%, compared to a ten-year decline of 12% on WeBS. Improved analysis of NEWS data helped to add some more birds to the open-coast estimate so the 10% fall may underestimate the seriousness of the Oystercatcher situation. The 25-year Oystercatcher decline on WeBS is 26%, which is not surprising if you look at the changes to breeding numbers in Scotland, where most British birds are to be found. There’s more about this in:  The Redshank decline of 26,000 is higher than would be predicted from WeBS figures, suggesting a drop of over 20% since APEP3, rather than ‘just’ 15% for the ten-year WeBS figure. This is a species that also features strongly in the Non-estuarine Waterbird Survey and that might explain the difference. Wintering Redshank are mostly of British and Icelandic origin, with the

The Redshank decline of 26,000 is higher than would be predicted from WeBS figures, suggesting a drop of over 20% since APEP3, rather than ‘just’ 15% for the ten-year WeBS figure. This is a species that also features strongly in the Non-estuarine Waterbird Survey and that might explain the difference. Wintering Redshank are mostly of British and Icelandic origin, with the  It has been suggested that the long-term declines of Grey Plover and Dunlin may be associated with short-stopping, with new generations of both species wintering closer to their eastern breeding grounds than used to be the case. WeBS results indicate a 31% drop in Grey Plover and a 42% drop in Dunlin, over the last 25 years. There was a loss of 10,000 for both species between APEP3 and the new review, representing declines of 23% and 3% respectively.

It has been suggested that the long-term declines of Grey Plover and Dunlin may be associated with short-stopping, with new generations of both species wintering closer to their eastern breeding grounds than used to be the case. WeBS results indicate a 31% drop in Grey Plover and a 42% drop in Dunlin, over the last 25 years. There was a loss of 10,000 for both species between APEP3 and the new review, representing declines of 23% and 3% respectively. One of the consequences of improved statistical techniques, as used this time around, is the apparent decline in the estimated population of Black-tailed Godwit. The new figure of 39,000 is 4,000 smaller than in APEP3, despite the fact that the WeBS graph clearly shows an increase. Interpolation using WeBs figures suggests that the earlier population estimate should have been 31,000, rather than 43,000.

One of the consequences of improved statistical techniques, as used this time around, is the apparent decline in the estimated population of Black-tailed Godwit. The new figure of 39,000 is 4,000 smaller than in APEP3, despite the fact that the WeBS graph clearly shows an increase. Interpolation using WeBs figures suggests that the earlier population estimate should have been 31,000, rather than 43,000. Snipe (Common): The winter estimate remains as 1,100,000 – a figure that was acknowledged in APEP3 as being less reliable than that of most species. At the same time, the GB breeding population was estimated as 76,000 pairs, indicating at least a 4:1 ratio of foreign to British birds, and that does not take account of the number of British birds that migrate south and west. Snipe are ‘amber listed’ but BBS suggests a recent increase of 26% (1995-2018). There is a WaderTales blog about

Snipe (Common): The winter estimate remains as 1,100,000 – a figure that was acknowledged in APEP3 as being less reliable than that of most species. At the same time, the GB breeding population was estimated as 76,000 pairs, indicating at least a 4:1 ratio of foreign to British birds, and that does not take account of the number of British birds that migrate south and west. Snipe are ‘amber listed’ but BBS suggests a recent increase of 26% (1995-2018). There is a WaderTales blog about  The paper in British Birds also includes a table of January population estimates, to provide data that are comparable to mid-winter counts in other countries. These figures are used in waterbird monitoring for the International Waterbird Census for the African Eurasian Flyway. The main table (and figures mentioned above) are average maximum winter counts (in the period September to March). Black-tailed Godwit is one species that illustrates the difference, with a mean of 30,000 in January and a mean peak count of 39,000. Having moulted in Great Britain, some Black-tailed Godwits move south to France and Portugal in late autumn, returning as early as February. January counts are therefore substantially lower than early-winter and late-winter counts. There is more about the migratory strategy employed by Black-tailed Godwits that winter in southern Europe in

The paper in British Birds also includes a table of January population estimates, to provide data that are comparable to mid-winter counts in other countries. These figures are used in waterbird monitoring for the International Waterbird Census for the African Eurasian Flyway. The main table (and figures mentioned above) are average maximum winter counts (in the period September to March). Black-tailed Godwit is one species that illustrates the difference, with a mean of 30,000 in January and a mean peak count of 39,000. Having moulted in Great Britain, some Black-tailed Godwits move south to France and Portugal in late autumn, returning as early as February. January counts are therefore substantially lower than early-winter and late-winter counts. There is more about the migratory strategy employed by Black-tailed Godwits that winter in southern Europe in  The authors have done a tremendous job. They have refined the way that estimates are calculated, they have combined the results from WeBS and NEWS III, and they have delivered population estimates for 25 wader species and many more other species of waterbirds. These population estimates will be used in conservation decision-making until the next set of numbers becomes available. Meanwhile, thousands of birdwatchers will count the birds on their WeBS patches in each winter month, every year. Without them, this paper could not have been written.

The authors have done a tremendous job. They have refined the way that estimates are calculated, they have combined the results from WeBS and NEWS III, and they have delivered population estimates for 25 wader species and many more other species of waterbirds. These population estimates will be used in conservation decision-making until the next set of numbers becomes available. Meanwhile, thousands of birdwatchers will count the birds on their WeBS patches in each winter month, every year. Without them, this paper could not have been written.

Why is Scotland losing its breeding waders? This WaderTales blog is a story from Strathallan, based on observations by Mike Bell.

Why is Scotland losing its breeding waders? This WaderTales blog is a story from Strathallan, based on observations by Mike Bell.

Establishing breeding requirements of Whimbrel

Establishing breeding requirements of Whimbrel