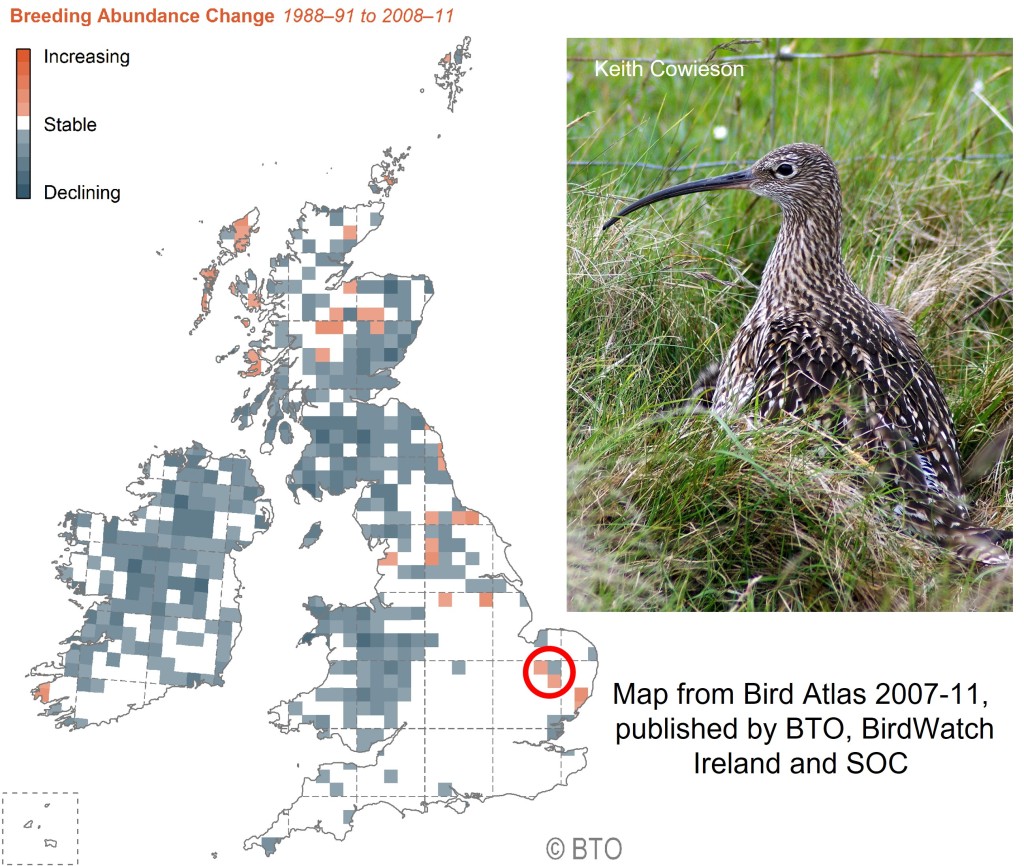

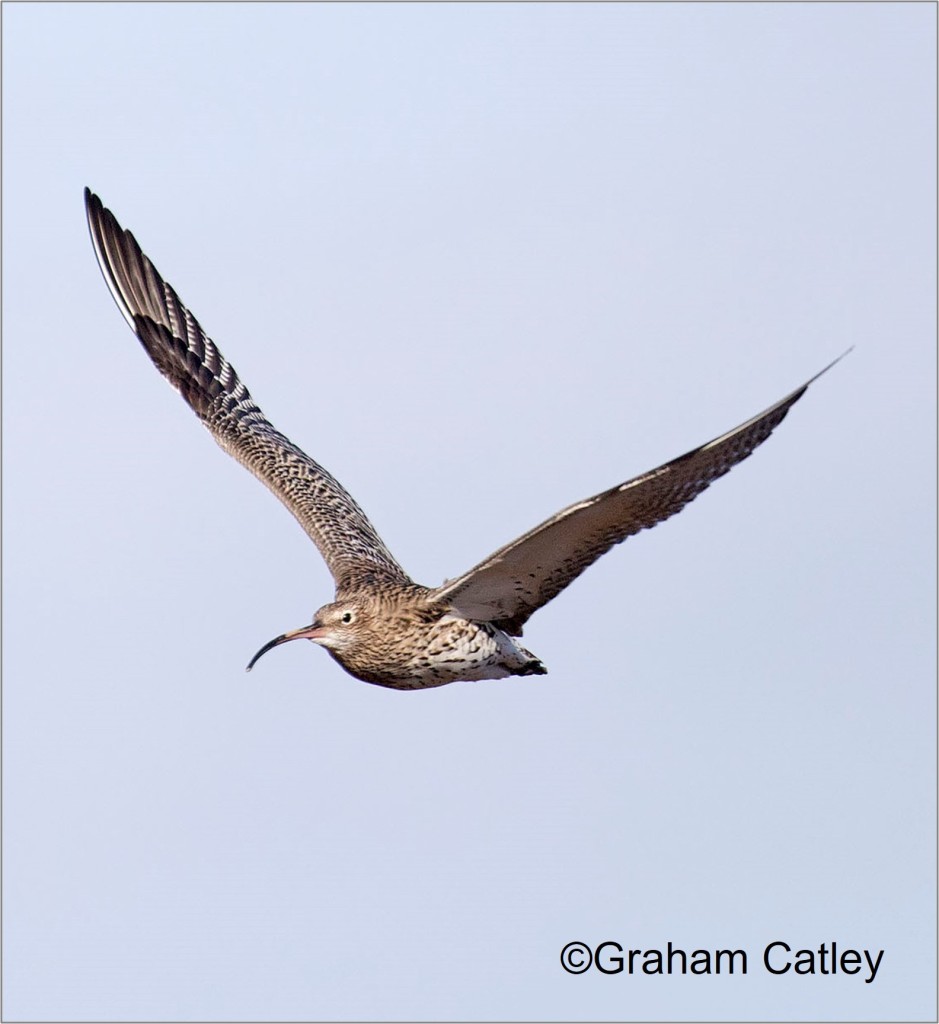

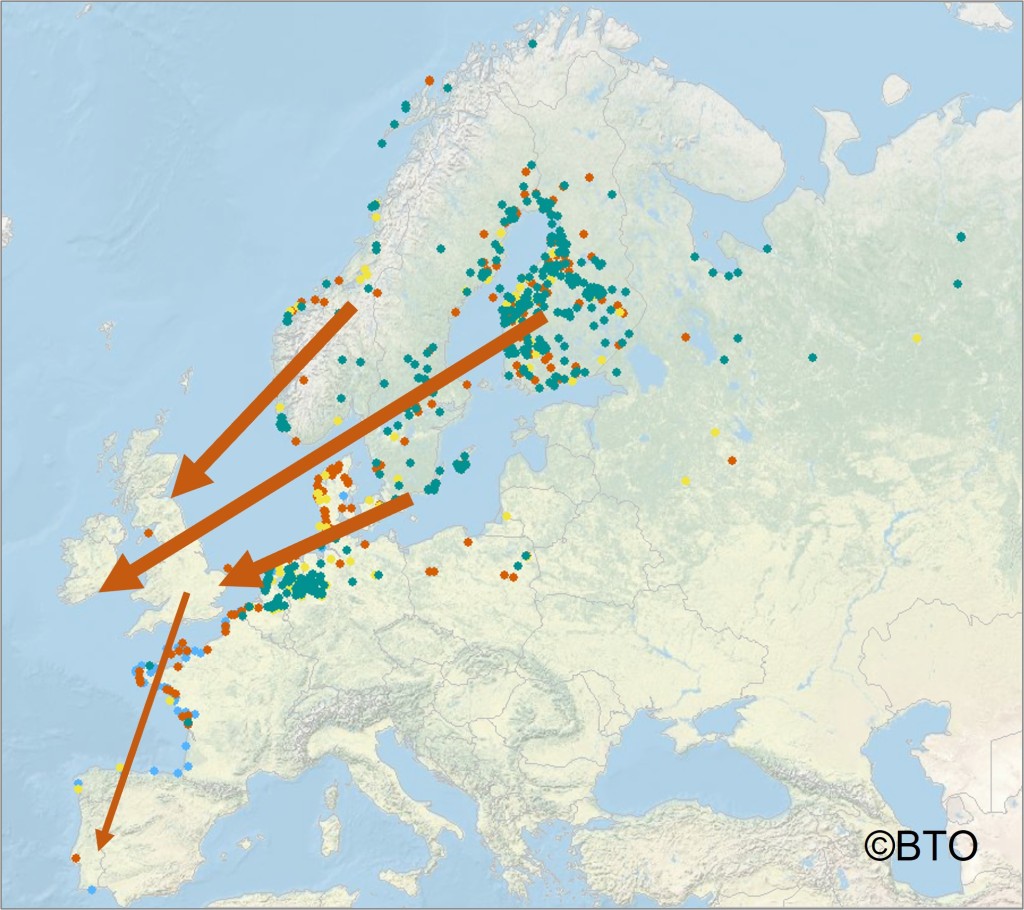

The Eurasian Curlew is designated as ‘Near-Threatened’ by IUCN/BirdLife. It is Red-listed in the UK, largely due to a rapid decline in breeding numbers. In this context, the fact that there are a few pink squares (indicating increased numbers) on the map showing breeding abundance change between 1988-91 and 2008-11 looks encouraging.

Why are Curlew doing relatively well in some areas and might these conditions be replicated? In a 2023 paper in IBIS, Harry Ewing examines how nest survival varies within Breckland, the area indicated by a red circle on the map alongside.

Curlew problems

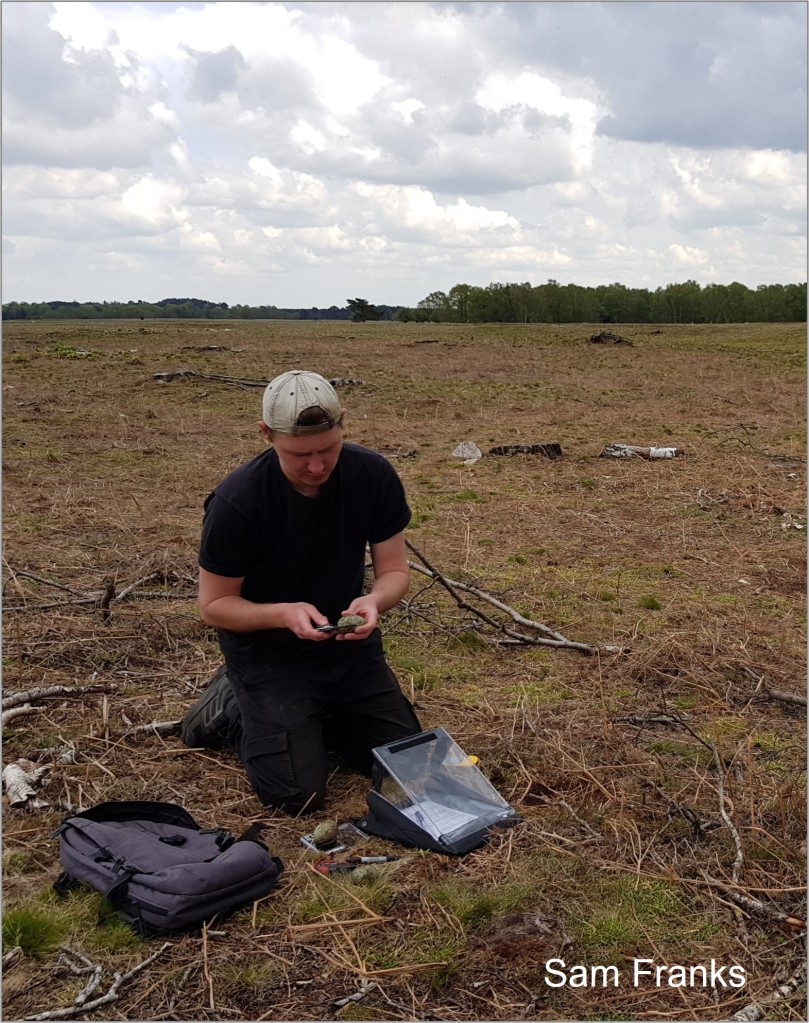

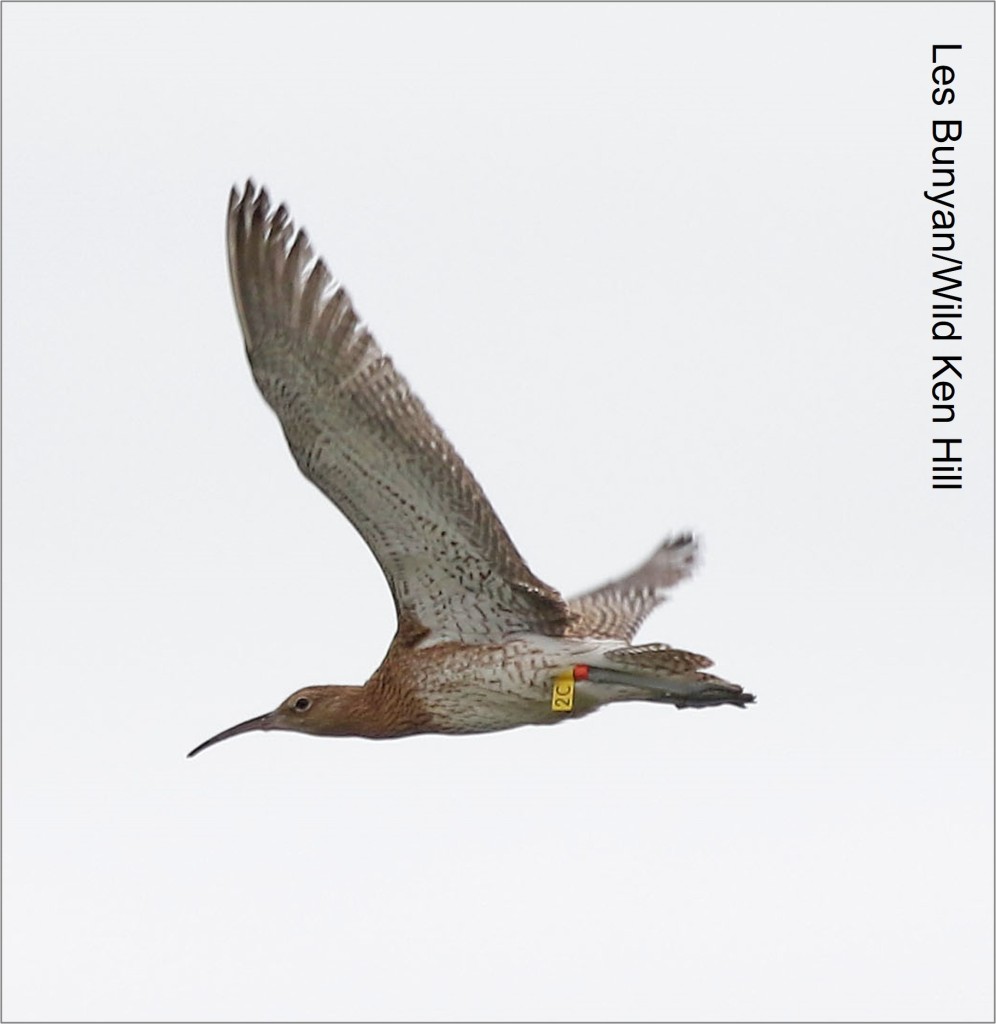

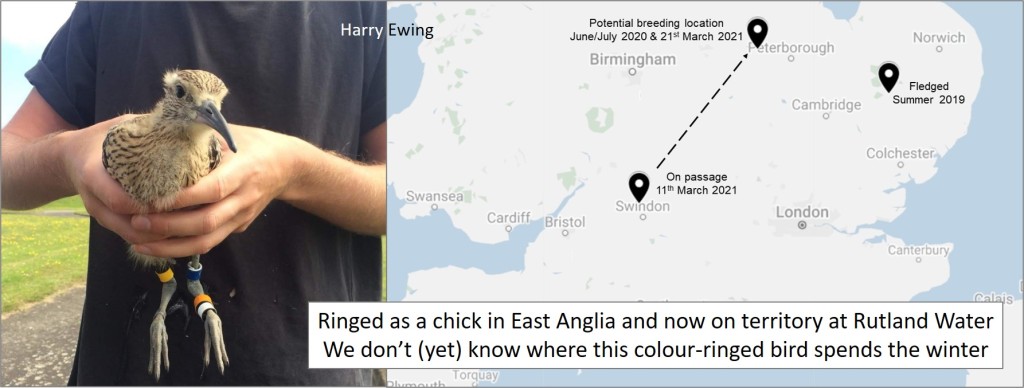

The landscape changes associated with declining numbers of British breeding Curlew were reviewed in a 2017 paper by Samantha Franks and colleagues and summarised in the WaderTales blog Curlews can’t wait for a treatment plan. In 2020, Aonghais Cook et al analysed annual survival rates of Curlews in Britain and concluded that these were remarkably high, strongly suggesting that productivity is the main problem, as discussed in More Curlew chicks needed. Harry Ewing, a PhD student at the University of East Anglia, has been studying Curlews breeding in Breckland since 2019, in the hope that he might find answers to the question “Are there circumstances in which England’s lowland Curlew breed successfully?” The answer has implications for Curlews in other areas.

Targeting help for Curlew

Visitors to UK wetland nature reserves are becoming used to seeing fenced areas, in which species such as Avocet and Lapwing can nest relatively successfully, out of the reach of mammalian predators. These fences tend to shine a spotlight on the role of mammalian predation in wader declines but this is only part of the problem.

Landscapes used by ground-nesting birds have been massively changed by agricultural intensification and afforestation, which may make nests more vulnerable to predation. Additionally, human-induced climate change is rapidly altering environmental conditions. It’s hard to hide a nest if the grass won’t grow and difficult for chicks to find insects in a drought.

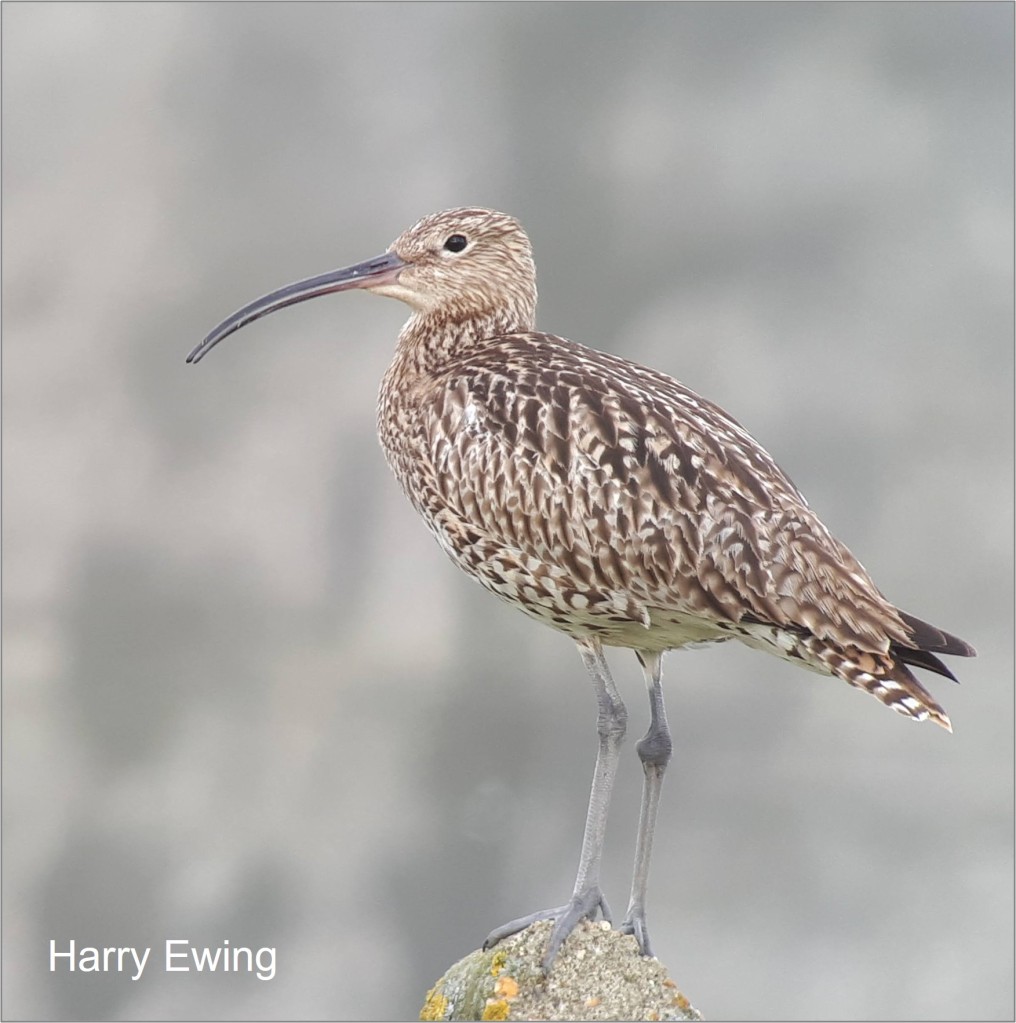

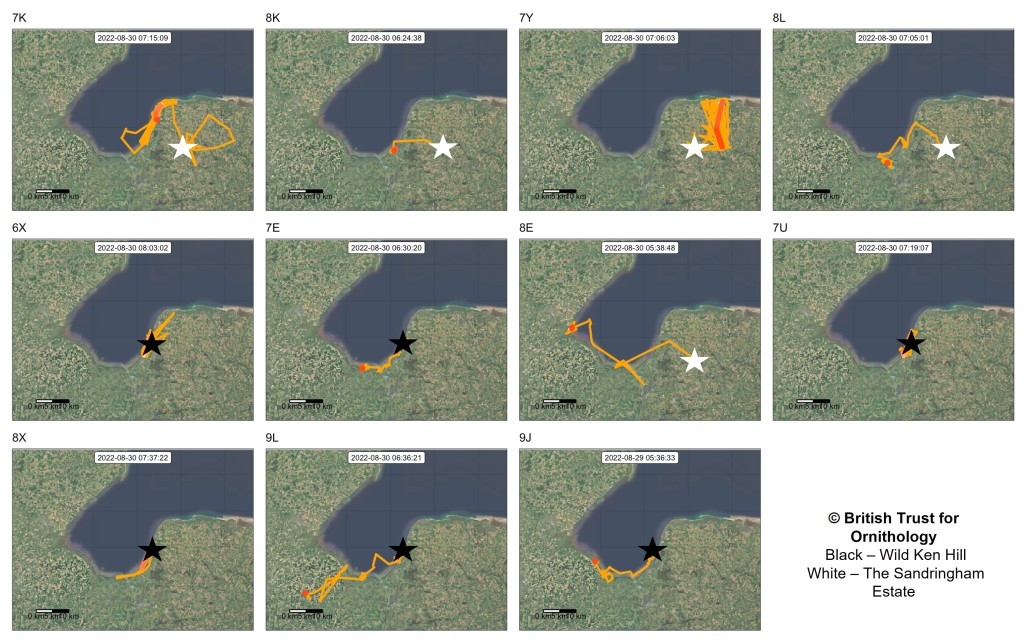

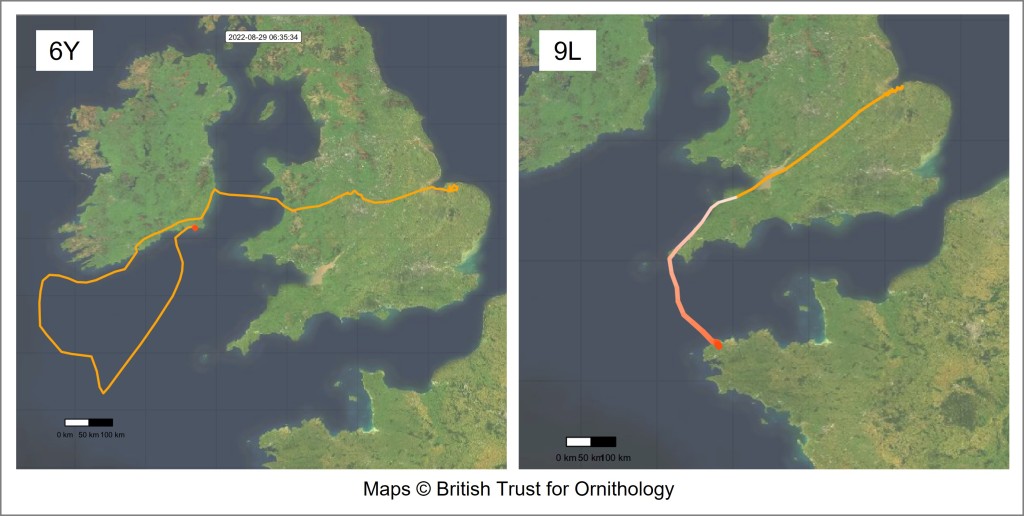

A set of tools is available to those managing land for semi-colonial waders in lowland wet grasslands (see Tool-kit for wader conservation). For Curlew breeding at much lower densities across human-modified landscapes, such as farmland, conservation is more challenging. In his IBIS paper, Harry Ewing quantifies variation in Curlew nest survival, in order to explore how management could be targeted to boost this key component of breeding productivity. Up to 80 pairs of Curlew were monitored annually between 2019 and 2021, in eight locations across Breckland, eastern England, an area in which nesting densities ranged from less than one to more than seven pairs per km2.

Breckland Curlew

The Brecklands of East Anglia have been shaped by humans for millennia. In their current form they comprise intensive farmland, commercial forestry plantations, and military bases and training areas, with pockets of land managed for the distinctive flora and fauna communities that used to be widespread across dry, grazed heath and grasslands. Curlew in Breckland can be found nesting alongside runways, within sugar-beet fields and on nature-reserves.

In this study, pairs were monitored across a range of sites and habitats, including arable farmland, grassland, cleared forest, a military training area and an RAF base. The eight study sites were dominated by arable fields or semi-natural grassland, which is maintained by mowing or livestock grazing. Public access was restricted and some areas within grassland sites were enclosed by fencing. None of the fences were designed to protect breeding waders but their presence around military bases and to reduce grazing pressure in forests potentially provide benefits for Curlew, by reducing fox encounters.

Most of the fieldwork was conducted in 2019 and 2021, when 55 and 69 nesting attempts were followed. Curlew nests can be hard work to locate, and anyone who has ever studied breeding Curlew will be impressed by these numbers! The 2020 season started late, due to Covid-19 restrictions, but added another 12 nests.

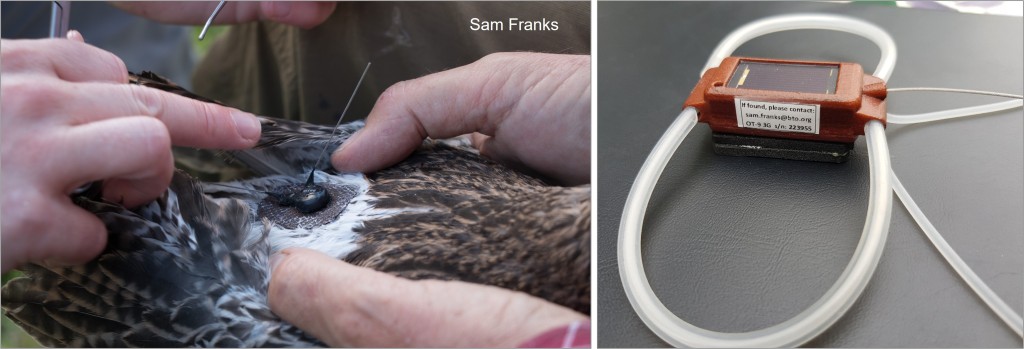

The location of each nest was recorded with a GPS device, an iButton temperature logger was deployed in the nest lining, in order to capture the timing of nest failures, and hatching dates were predicted from the weights and measurements of eggs (more details in the paper). Regular monitoring and more frequent visits close to hatch date provided information on nest outcomes. Nest concealment was recorded on the day on which each nest was located, by measuring the height of vegetation around the nest.

Assessing nesting success

Curlew breed in a wide range of densities across the Breckland study area. Six sites held between 0.17 and 0.72 pairs per km2, while two other hosted densities of between 3.3 and 7.4 pairs per km2. Nearly half of the probable or confirmed breeding pairs monitored annually were on the latter two sites, despite the fact that between them they only accounted for 5% of the study area.

A total of 136 Curlew nests were monitored across Breckland over the three summers, with the majority being found in unfenced grassland areas. 185 chicks hatched from 52 nests and 84 nests failed. Predation accounted for 86% of nest failures, with three nests failing during laying, one being trampled by cattle and five being lost during farming activities.

The key result in the paper is that hatching success was not high enough, in any habitat, in any year. There was some variation between sites but the mean probability of surviving incubation, for all hatched or predated nests was about 0.25, which is well below the estimated requirement for sustainability of a population.

Nest survival was similar in unfenced grassland, fenced grassland, arable fields and ground-disturbance plots within grassland, and across levels of nest concealment, so the spatial variation in nest survival was not the result of variation in management conditions or of nest concealment between sites. Only nine nests were found in fenced areas, making it unlikely that any positive effect of fencing could have been detected.

For nests for which data from temperature-loggers were available, it was possible to infer that 36 out of 44 predation events took place during the (short) nocturnal period, the time when foxes are most active.

Implications for Curlew conservation

It would have been great if Harry had been able to find a prescription for Curlew nesting success, by identifying a set of circumstances that delivered plenty of chicks. The fact that this was not possible, despite monitoring a large number of pairs, in a variety of habitats and across a broad density gradient, emphasises how hard it is going to be to preserve Curlew as a breeding species in England. Head-starting (raising chicks in captivity) may be able to give a temporary boost to numbers (see Will head-starting work for Curlew?) but these new recruits need to be able to breed successfully if local populations are going to be sustainable.

As the great majority (86%) of nests failed because of predation, boosting hatching rates of Curlew nests is likely to require actions to reduce mammalian predator impact across large areas of Breckland. It is much harder to help thinly-spread Curlew than semi-colonial Lapwing.

A conservation tool that is commonly deployed to reduce predation on ground-nesting birds’ nests is predator-exclusion fencing. Fences have the potential to double wader hatching rates in species such as Lapwing (Malpas et al. 2013) and it seems likely that they could also be effective at boosting Curlew nest survival, if provided at an appropriate scale.

In Breckland, fences were not deployed to protect Curlew nests A small number of pairs nested within fenced areas but too few to detect an observable effect of fencing on nest survival. Increasing the number of nests enclosed by predator fencing in Breckland could potentially be achieved by deploying temporary electric fencing to protect individual nests but the substantial annual efforts required to locate nests and erect and maintain fences make this impractical, especially in areas where Curlew breed at very low densities.

The authors suggest that targeted deployment of fencing could potentially be effective if focused on ground-disturbance plots within grassland (see graphic below). These areas were originally developed for Stone-curlew but are often used by nesting Curlew, as described in a paper by Natalie Zielonka et al and summarised in Curlews and foxes in East Anglia. Plot-level fencing could be deployed at the start of the season, without the need to locate nests, and may benefit other ground-nesting species such as Lapwing. Unfortunately, these plots currently only support between four and seven breeding pairs of Curlew in the study area, suggesting only a modest potential increase in chick production.

Another alternative might be to erect permanent barrier fences along the boundaries of sites supporting high densities of nesting Curlew. Fencing the combined boundary length of the eight Breckland study sites that between them support about 80 pairs would require 185 km of fencing, which would be prohibitively expensive. However, given that nearly half of these pairs were breeding in just two of those sites, with a combined boundary length of only 14 km, perhaps this is where efforts might be focused? Assuming such fences would be as effective as for other waders, enclosing these two high-density sites with permanent barrier fencing could potentially boost the total number of chicks hatched in Breckland by about 90 chicks per year. It would be interesting to calculate whether this might be a more cost-effective way of producing fledged chicks than head-starting.

To sustainably maintain and recover Curlew populations in the wider landscape, in Breckland and elsewhere across the breeding range, actions outwith fenced areas are likely to be required. Lethal control of foxes, the main mammalian nest predator in the region, occurs across much of the Breckland study area and it would be useful to know how effective it is at limiting nest predation levels. This means learning more about predation, predator behaviour and control measures.

Across England, regional stakeholder networks are going to be important. Curlew territories are large and pairs move between habitats, implying a need to integrate evidence-based, Curlew-friendly policies into large-scale agri-environment schemes. Harry Ewing and his co-authors suggest that the next steps are to work with stakeholders to trial management actions for Curlew (e.g., fencing, head-starting and predator control). Actions to boost nest survival will need to be targeted in areas that contain suitable habitat to support chick growth and survival. Further research is required to understand the land management actions that can create and maintain such conditions at different scales.

To find out more

This blog focuses on the first paper from Harry Ewing’s thesis, undertaken by the University of East Anglia on a Natural Environment Research Council CASE studentship, as part of the EnvEast DTP. It was part funded by the British Trust of Ornithology, with support from RSPB and via a Defence Infrastructure Organisation Environmental Stewardship grant.

Nest survival of threatened Eurasian Curlew (Numenius arquata) breeding at low densities across a human-modified landscape. Harry Ewing, Samantha Franks, Jennifer Smart, Niall Burton & Jennifer A Gill. IBIS. doi.org/10.1111/ibi.13180

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton (@GrahamFAppleton) to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on published papers, with the aim of making shorebird science available to a broader audience.

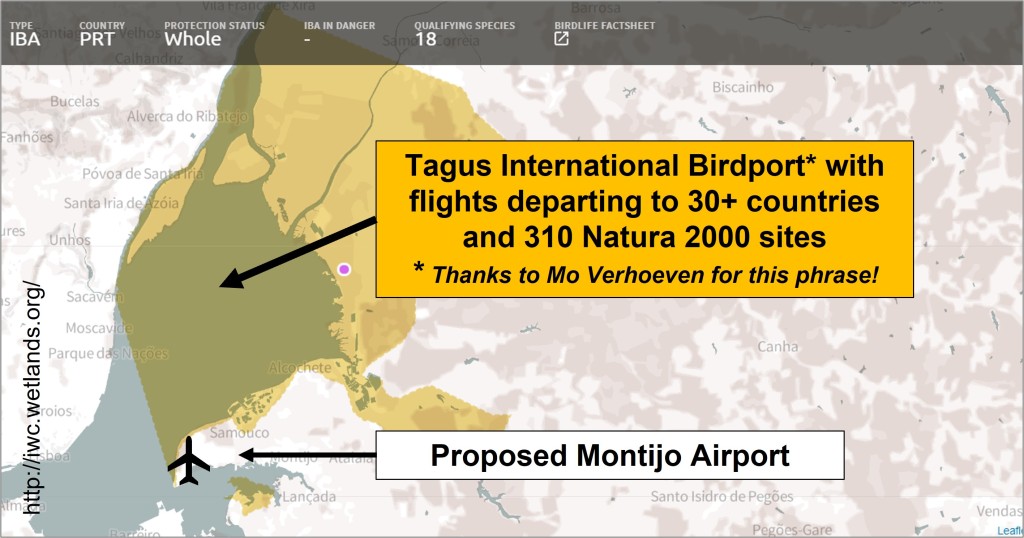

With Curlew populations in free-fall across much of the British Isles, researchers are trying to understand the reasons for poor breeding performance. At the same time, several groups are trialling emergency interventions, such as predator control and predator exclusion, to try to boost the number of fledged chicks. Sharing knowledge is crucial, so it’s great that a 2020 paper by Natalia Zielonka and colleagues in Bird Study adds to our understanding of nest-site selection and the reasons for nesting failures.

With Curlew populations in free-fall across much of the British Isles, researchers are trying to understand the reasons for poor breeding performance. At the same time, several groups are trialling emergency interventions, such as predator control and predator exclusion, to try to boost the number of fledged chicks. Sharing knowledge is crucial, so it’s great that a 2020 paper by Natalia Zielonka and colleagues in Bird Study adds to our understanding of nest-site selection and the reasons for nesting failures.

Much of the research underpinning the above review was conducted in upland areas. What is happening in the flatlands of East Anglia and might any differences explain the apparent resilience – or even growth – of this population? Most lowland Curlew breed on dry grasslands and heathland, where physical ground-disturbance is increasingly advocated as a land management technique for other rare, scarce and threatened species, such as Stone-Curlew and Woodlark. How do these interventions affect breeding Curlew in the same areas?

Much of the research underpinning the above review was conducted in upland areas. What is happening in the flatlands of East Anglia and might any differences explain the apparent resilience – or even growth – of this population? Most lowland Curlew breed on dry grasslands and heathland, where physical ground-disturbance is increasingly advocated as a land management technique for other rare, scarce and threatened species, such as Stone-Curlew and Woodlark. How do these interventions affect breeding Curlew in the same areas?

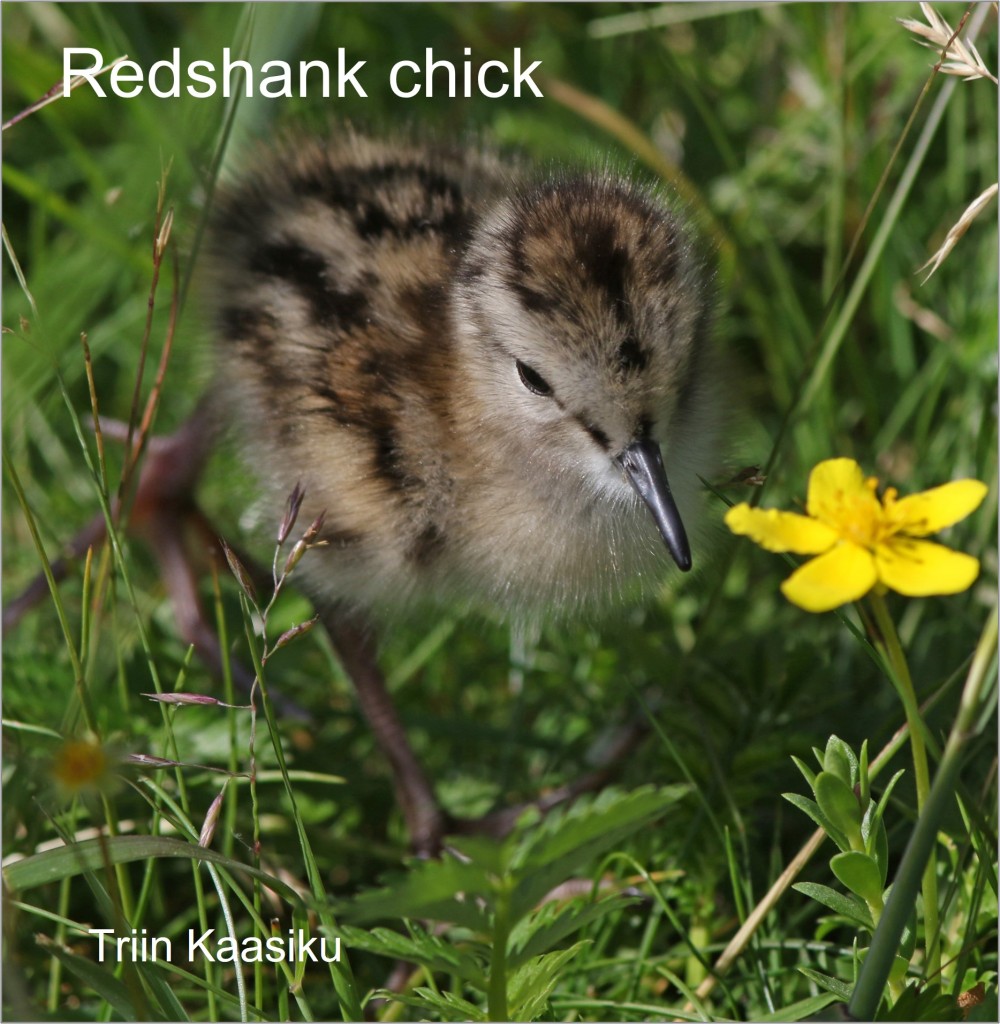

To determine the date and timing of nest failure, temperature sensors were placed under the eggs. Nests were remotely checked every three-to-seven days, to confirm adults were still incubating, and the scrape was visited once a week to record any predation events (e.g. partial clutch predation). From three days before the predicted hatch date, nests were remotely monitored daily to accurately determine their fate. After hatching, the nest site was visited every three-to-five days, to observe adults and chicks from a vehicle, continuing until the chicks fledged or the breeding attempt had failed.

To determine the date and timing of nest failure, temperature sensors were placed under the eggs. Nests were remotely checked every three-to-seven days, to confirm adults were still incubating, and the scrape was visited once a week to record any predation events (e.g. partial clutch predation). From three days before the predicted hatch date, nests were remotely monitored daily to accurately determine their fate. After hatching, the nest site was visited every three-to-five days, to observe adults and chicks from a vehicle, continuing until the chicks fledged or the breeding attempt had failed.

The key finding of this project is that physical ground-disturbance, which is advocated as a conservation measure within lowland dry grassland and grass-heath for many rare, scarce and threatened species, also provides suitable Curlew nesting habitat, with no reduction in nest survival. Implementing ground-disturbance, particularly through shallow-cultivating, in areas with few or no mammalian nest predators, could provide a useful management tool for attracting breeding Curlew to safer areas.

The key finding of this project is that physical ground-disturbance, which is advocated as a conservation measure within lowland dry grassland and grass-heath for many rare, scarce and threatened species, also provides suitable Curlew nesting habitat, with no reduction in nest survival. Implementing ground-disturbance, particularly through shallow-cultivating, in areas with few or no mammalian nest predators, could provide a useful management tool for attracting breeding Curlew to safer areas. The paper at the heart of this blog is:

The paper at the heart of this blog is: Graham (

Graham (