For ornithologists studying birds by adding colour-rings, flags and tracking devices, a question of fundamental importance is always “am I affecting the birds’ survival or behaviour by requiring them to carry these markers?” This is not just a welfare issue; if marking birds affects the way that birds behave or changes their chance of survival then any findings are dubious. In a paper in Journal of Field Ornithology, Emily Weiser explores whether leg flags influence the nesting success of four species of small wader (shorebird).

Using leg-flags

Western Sandpiper

Rings rarely have any negative effects on birds and are frequently used to mark individuals. Leg flags are bigger and easier to see, and there is space to add letters/numbers, but they are also bulkier and heavier. Might there be a consequence of flag-wearing for the nesting success or survival of individuals? By analysing nesting-success data collected at seven sites in Arctic Alaska and western Canada, Emily Weiser and colleagues were able to check for flag effects on four species of Arctic-breeding shorebird: Semipalmated and Western Sandpipers and Red-necked and Grey (Red) Phalaropes. The study involved measuring daily survival rates for nearly 2000 nests – which is a huge sample size. The amount of work involved is reflected in the fact that the Weiser paper has 24 authors!

A flag is a plastic strip shaped to wrap around a bird’s leg. It is like a colour-ring but with a tab that extends from the leg, increasing its conspicuousness and providing an opportunity to inscribe a letter/number code. The probability of generating individual sightings can be increased but at what costs? Might flags make nesting birds more obvious to predators? Could the bulkier flag damage the eggs? Might the flag affect incubation efficiency? Whilst it was not possible to answer each of these questions separately, the total effect could be measured by checking to see if nest survival was different for birds wearing flags, as opposed to rings.

A flag is a plastic strip shaped to wrap around a bird’s leg. It is like a colour-ring but with a tab that extends from the leg, increasing its conspicuousness and providing an opportunity to inscribe a letter/number code. The probability of generating individual sightings can be increased but at what costs? Might flags make nesting birds more obvious to predators? Could the bulkier flag damage the eggs? Might the flag affect incubation efficiency? Whilst it was not possible to answer each of these questions separately, the total effect could be measured by checking to see if nest survival was different for birds wearing flags, as opposed to rings.

Findings

Male Red-necked Phalarope

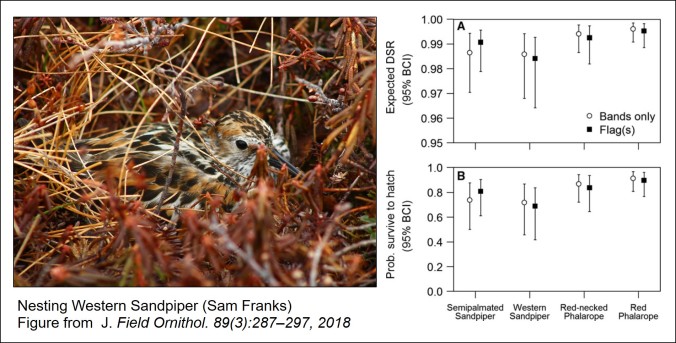

Between 205 and 780 nests of the four species of Arctic-breeding shorebirds were included in the study, with between 36% and 82% of these nests having at least one adult with a leg flag in attendance. For the two sandpipers (Western and Semipalmated), the sample included nests with two flagged parents, about half as many where only one parent had a flag and others where parents wore colour-rings (bands), rather than flags. Female phalaropes do not brood their eggs so, for Red-necked and Grey (Red) Phalaropes, nests were categorised by whether males wore flags, or just colour-rings. Several different analyses were carried out, to take account of the number of flagged parents, year effects etc., as you can read in the paper, but there is one key result; there is no evidence that leg flags affect the daily survival rate (DSR) of the nests for any of the four species, or the probability that a nest is successful (see figure).

Across the whole incubation period, the proportion of nests expected to hatch did not differ between nests with or without flagged adults. There was variation between species, with the estimated probability of eggs hatching varying from 70% for Western Sandpiper to 91% for Grey (Red) Phalarope. These figures are higher than reported previously because the analysis was only for nests where at least one bird was captured. Early failures were therefore excluded. Overall nest success rates are reported in this paper.

A mix of species

Colour-ringed Red-necked Phalarope

This study focused on four small species of wader, from Semipalmated Sandpiper (26g) to Grey (Red) Phalarope (49g), in which any effects of (relatively large) flags on breeding success might be expected to be higher than for larger species of wader. The results are very similar, despite the fact that sandpipers and phalaropes differ in two potentially important ways:

- The species behave very differently, using very different feeding methods – phalaropes feed mainly on water, while the two sandpipers feed on land and at the land-water interface

- In sandpipers, both parents attend the nest but in phalaropes only one parent (the male) attends the nest.

Could flags have other effects?

Flagged Semipalmated Sandpiper

Nothing in the data analysed for this paper suggests that flags are affecting survival rates of marked birds during the period when birds are breeding. The authors suggest that it would be useful to undertake further analyses to check:

- Nest survival rates for a broader range of species and in different habitats (where, for instance, predators might behave differently).

- Growth rates of chicks wearing flags and of chicks being cared for by parents wearing flags.

- Annual survival rates of adults and chicks that wear flags.

Emily Weiser has also written a review of the effects of leg-mounted geolocators on waders/shorebirds. Here she found that there could be problems in a small number of circumstances. This important paper is summarised in this blog: Are there costs to wearing geolocators?

Another WaderTales blog examines the preening and feeding behaviour of Green Sandpipers that wear geolocators attached to harnesses.

More in the paper

Emily Weiser in the field

Any researchers who wish to investigate the effects of marking birds will find it useful to read the whole paper, for details of methods and analyses. There is also a long list of references relating to the effects of marking birds. Information about the particular types of flags used in these studies may also be helpful.

Effects of leg flags on nest survival of four species of Arctic-breeding shorebirds: Emily L. Weiser, Richard B. Lanctot, Stephen C. Brown, H. River Gates, Rebecca L. Bentzen, Megan L. Boldenow, Jenny A. Cunningham, Andrew Doll, Tyrone F. Donnelly, Willow B. English, Samantha E. Franks, Kirsten Grond, Patrick Herzog, Brooke L. Hill, Steve Kendall, Eunbi Kwon, David B. Lank, Joseph R. Liebezeit, Jennie Rausch, Sarah T. Saalfeld, Audrey R. Taylor, David J. Ward, Paul F. Woodard and Brett K. Sandercock Field Ornithol. 89(3):287–297, 2018 DOI: 10.1111/jofo.12264

Graham (@grahamfappleton) has studied waders for over 40 years and is currently involved in wader research in the UK and in Iceland. He was Director of Communications at The British Trust for Ornithology until 2013 and is now a freelance writer and broadcaster.

Moult is an energetic process, especially the post-breeding moult, which includes a change of all of the wing and tail feathers. To complete the whole process, birds ideally need to find a three-month period when resources are good, climatic conditions are benign and there is no need to migrate. For birds on the East Atlantic Flyway that spend the non-breeding season in Europe, moult typically takes place after the breeding season and before days get shorter and the weather gets colder.

Moult is an energetic process, especially the post-breeding moult, which includes a change of all of the wing and tail feathers. To complete the whole process, birds ideally need to find a three-month period when resources are good, climatic conditions are benign and there is no need to migrate. For birds on the East Atlantic Flyway that spend the non-breeding season in Europe, moult typically takes place after the breeding season and before days get shorter and the weather gets colder.

Up to one million Golden Plovers arrive in Iceland each spring, mainly from Ireland and western parts of the United Kingdom. This is estimated to be nearly half of the European breeding population. Iceland might seem small, when compared to the vast land-mass of the European continent, but it’s a haven for waders. This status is threatened by the spread and intensification of lowland farming, increased afforestation and by the ‘summer cottage’ industry – but those are stories for another day.

Up to one million Golden Plovers arrive in Iceland each spring, mainly from Ireland and western parts of the United Kingdom. This is estimated to be nearly half of the European breeding population. Iceland might seem small, when compared to the vast land-mass of the European continent, but it’s a haven for waders. This status is threatened by the spread and intensification of lowland farming, increased afforestation and by the ‘summer cottage’ industry – but those are stories for another day. The Heiðlóa (Golden Plover) is a welcome sight and sound at the end of the Icelandic winter. The first migrants appear about 23 March and nesting can commence as early as 26 April. The usual clutch size is four eggs, with both parents sharing incubation duties. Some first nests are lost, due to predation, but females can lay another clutch. Joop Jukema studied Golden Plovers nesting near Selfoss in the Southern Lowlands of Iceland, timing his captures of nesting birds to coincide with the later part of the incubation period. He was able to assess the progress of moult by scoring the growth of the primary feathers and to work out when each bird would have dropped its first primary. The estimated mean start date of primary moult for males was 19 May (95% confidence interval 27 April – 10 June) with females starting an average of 9 days later, on 28 May (95% confidence interval 6 May – 19 June). On average, males started to moult their primary feathers nine days before the start of incubation, while females started to moult at the same time as incubation began. Potentially, hormone changes associated with the stage of the breeding season could be linked to the onset of moult.

The Heiðlóa (Golden Plover) is a welcome sight and sound at the end of the Icelandic winter. The first migrants appear about 23 March and nesting can commence as early as 26 April. The usual clutch size is four eggs, with both parents sharing incubation duties. Some first nests are lost, due to predation, but females can lay another clutch. Joop Jukema studied Golden Plovers nesting near Selfoss in the Southern Lowlands of Iceland, timing his captures of nesting birds to coincide with the later part of the incubation period. He was able to assess the progress of moult by scoring the growth of the primary feathers and to work out when each bird would have dropped its first primary. The estimated mean start date of primary moult for males was 19 May (95% confidence interval 27 April – 10 June) with females starting an average of 9 days later, on 28 May (95% confidence interval 6 May – 19 June). On average, males started to moult their primary feathers nine days before the start of incubation, while females started to moult at the same time as incubation began. Potentially, hormone changes associated with the stage of the breeding season could be linked to the onset of moult.

Female Golden Plovers left the Ammarnäs breeding territories at the end of July. From observations of females caught on their nests, it seemed likely that individual females were not starting the moult of their outer primaries, typically completing the moult of primary four and not dropping primary five. Males stayed with chicks for an extra fortnight. Given the longer period of time available to males, it is likely that they were able to moult more primary feathers than their partners, prior to departure from the area.

Female Golden Plovers left the Ammarnäs breeding territories at the end of July. From observations of females caught on their nests, it seemed likely that individual females were not starting the moult of their outer primaries, typically completing the moult of primary four and not dropping primary five. Males stayed with chicks for an extra fortnight. Given the longer period of time available to males, it is likely that they were able to moult more primary feathers than their partners, prior to departure from the area. Overlapping the breeding and moulting period is rare in migratory birds but it makes sense in a time-constrained annual cycle. The research team suggest that Icelandic plovers presumably need to initiate moult early in the season, in order to be able to complete it at the breeding grounds. This is not an option for Continental plovers, as their breeding season is much shorter, due to a harsher climate and an earlier drop-off in the number of arthropods, their main food source. These Golden Plovers cannot delay the start of the moult period until after the autumn migration because there is insufficient time to compete a full moult in areas such as Lund or the Netherlands, prior to the onset of winter frosts. The fact that Golden Plover are largely associated with farmland, rather than estuarine sites, may make them more susceptible to sub-zero temperatures than, for instance Grey Plover.

Overlapping the breeding and moulting period is rare in migratory birds but it makes sense in a time-constrained annual cycle. The research team suggest that Icelandic plovers presumably need to initiate moult early in the season, in order to be able to complete it at the breeding grounds. This is not an option for Continental plovers, as their breeding season is much shorter, due to a harsher climate and an earlier drop-off in the number of arthropods, their main food source. These Golden Plovers cannot delay the start of the moult period until after the autumn migration because there is insufficient time to compete a full moult in areas such as Lund or the Netherlands, prior to the onset of winter frosts. The fact that Golden Plover are largely associated with farmland, rather than estuarine sites, may make them more susceptible to sub-zero temperatures than, for instance Grey Plover.

A key finding of this paper is that splitting the moult period extends the total period of primary moult. For Swedish breeders, this is the best option, however, as there is insufficient time to complete autumn moult close to the breeding grounds or after the breeding season. As the authors conclude, “Meeting the energy demands of breeding, moult, and migration calls for different timing and spacing of these events in their annual cycle, adjusted to conditions at their breeding and stopover sites, and to their migration strategy.”

A key finding of this paper is that splitting the moult period extends the total period of primary moult. For Swedish breeders, this is the best option, however, as there is insufficient time to complete autumn moult close to the breeding grounds or after the breeding season. As the authors conclude, “Meeting the energy demands of breeding, moult, and migration calls for different timing and spacing of these events in their annual cycle, adjusted to conditions at their breeding and stopover sites, and to their migration strategy.”