More and more trees are being planted in lowland Iceland – and further increases are planned, in part encouraged by the suggestion that this will mitigate for climate change. Forestry is potentially bad news for Whimbrel, Black-tailed Godwit and other waders that breed in open habitats, and which migrate south to Europe and Africa each autumn. Are there ways to accommodate trees while reducing the damage to internationally important populations of waders?

Pressure on Iceland’s breeding waders

Iceland is changing; more people want second homes in the countryside, the road network is being developed to cope with more and more tourists, new infrastructure is needed to distribute electricity, agriculture is becoming more intensive and there is a push to plant lots more trees. The south of the country is seeing the most rapid loss of open spaces, providing opportunities to study how these incursions affect ground-nesting species, particularly breeding waders.

One of the big changes, especially in Southern Iceland, has been the planting of non-native trees, as shelter belts around fields and country cottages and, more significantly, as commercial crops. Iceland has been largely treeless for hundreds of years but climatic amelioration has facilitated rapid forestry development in areas where tree growth was previously limited by harsher environmental conditions. Seeds of some non-native species are blown on the wind for a kilometre or more, to germinate in open land, well beyond the edge of planned forests.

Most of the new forests are in lowland areas, where we also find the most important habitats for many ground-nesting bird populations. Lodgepole pines may be good news for Goldcrest and Crossbills but not for species such as Golden Plover, Dunlin & Redshank. For breeding waders, the most obvious impact of a new forest is direct loss of breeding habitat but trees can have wider effects, by providing cover for predators and breaking up swathes of open land that are used at different stages of the breeding season. Little is currently known about how predators in Iceland use forest plantations but any perceived risks of predator presence and reduced visibility is likely to influence densities of birds in the surrounding area.

Aldís E. Pálsdóttir’s studied changing bird populations in lowland Iceland during her PhD at the University of Iceland, in collaboration with researchers from the University of East Anglia (UK) and the University of Aveiro (Portugal). Among the most concerning of these changes is the rapid expansion of forestry in these open landscapes.

Assessing the potential impacts of trees

In a 2022 paper in the Journal of Applied Ecology, Aldís assesses whether densities of ground-nesting birds are lower in the landscape surrounding plantations and whether these effects vary among plantations with differing characteristics. She and her fellow authors then quantified the potential impact of differing future afforestation scenarios on waders nesting in lowland Iceland.

Forestry currently covers about 2% of Iceland’s land area so the potential for growth is massive. In 2018, the Icelandic government provided additional funding to the Icelandic forest service to increase the number of trees planted, with a goal of enhancing carbon sequestration. As forestry primarily operates through government grants to private landowners, who plant trees within their own land holdings, plantations typically occur as numerous relatively small patches in otherwise open landscapes. These features make Iceland an ideal location in which to quantify the way that plantations affect densities of birds in the surrounding habitats, and to identify afforestation strategies that might reduce impacts on globally important wader populations.

To measure the effects of plantation forests on the abundance and distribution of ground-nesting birds, in particular waders, 161 transect surveys were conducted between May and June 2017. To avoid systematic bias arising from possible “push effects” of corralling birds in front of the surveyor, surveys were conducted along transects that started either at the edge of the plantation, with the observer moving away (79 transects), or started away from the plantation, with the observer walking towards it (82 transects). Please see the paper for the full methodology. The variation in density with distance from plantation was used to estimate the likely changes in bird numbers, resulting from future afforestation plans, and to explore the potential effects of different planting scenarios.

Bird communities change around plantations

On the transects, 3713 individual birds of 30 species were recorded. The nine most common species (excluding gulls, which rarely breed in the focal habitats) were seven waders (Oystercatcher, Golden Plover, Dunlin, Common Snipe, Whimbrel, Black-tailed Godwit & Redshank) and two passerines (Meadow Pipit & Redwing). These species accounted for 88% of all birds recorded.

- Of the seven waders, Snipe was the only one found in significantly higher numbers closer to plantations. Snipe density declined by approximately 50% between the first (0-50 m) and second (50-100 m) distance intervals, suggesting a highly localised positive effect of plantations on Snipe densities.

- Densities of Golden Plover, Whimbrel, Oystercatcher, Dunlin and Black-tailed Godwit all increased significantly with increasing distance from plantations. Dunlin and Oystercatcher showed the largest effect (~15% increase per 50 m), followed by Whimbrel (~12%), Black-tailed Godwit (~7%) and Golden plover (~4%).

- Although Redshank did not show a linear relationship with distance from plantation edges, densities were lowest close to the plantation edge.

- There were more Redwings close to woodland edges but Meadow Pipit showed no change in density with distance from plantations.

Golden Plover, Whimbrel and Snipe were found in lower densities close to the tallest plantations (over 10 m), when compared to younger plantations (tree height 2m to 5m), suggesting that the impact of forests gets more pronounced as the trees grow. Plantation density and diameter had no additional effect on the species that were in lower densities closer to the plantations, implying that the mere presence of plantations induces the observed changes in abundance. See the paper for more details.

The bigger picture

Aldís Pálsdóttir and Harry Ewing walked every step of every transect and made detailed counts of what they saw – data that are invaluable when considering local impacts of plantations – but the paper becomes even more interesting when the authors look at the bigger picture. When plantations are distributed across these open landscapes, in different configurations, what will be the accumulated effects on the numbers of breeding waders? They estimate likely changes in abundance resulting from planting 1000 ha of plantation in different planting scenarios, ranging from a single block to lots of small patches.

- Planting 50 smaller patches of 20 ha, instead of 1000 ha of forest in one large patch, is estimated to double the resulting decline in abundance (because there is more forest edge and hence a bigger effect on more open habitat)

- This effect increases even further as the patches become smaller; in their models, planting 1000 blocks each of 1 ha would have nine times the impact of planting one forest of 1000 ha.

- Proximity of woodland seems to be the driver of local distributions of breeding waders so the authors suggest that the amount of edge (relative to area) should be minimised, to reduce the impact of a plantation – which means making forests as near circular as possible.

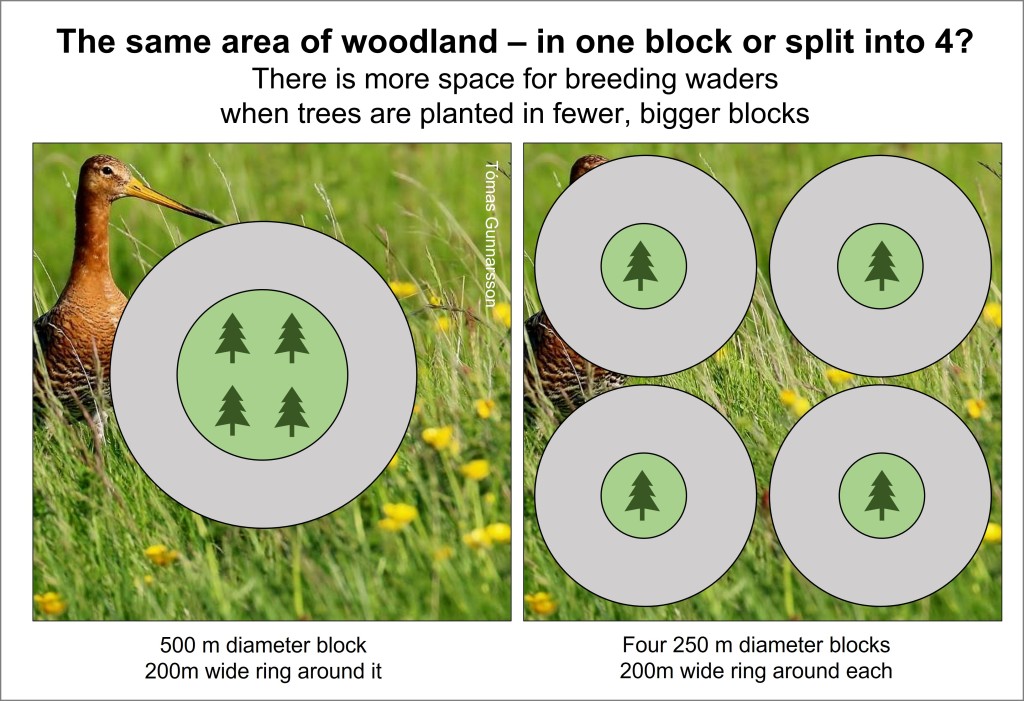

It is clear that fewer larger forestry plots are likely to be less bad than lots of small, local plantations, in terms of the effects on wader populations. The figure below illustrates how much more land is affected when one woodland is replaced by four with the same total area. The grey area (equivalent to a 200 metre annulus) accounts for 88 hectares in the one-patch illustration and 113 hectares for four patches.

An urgent need for action (and inaction!)

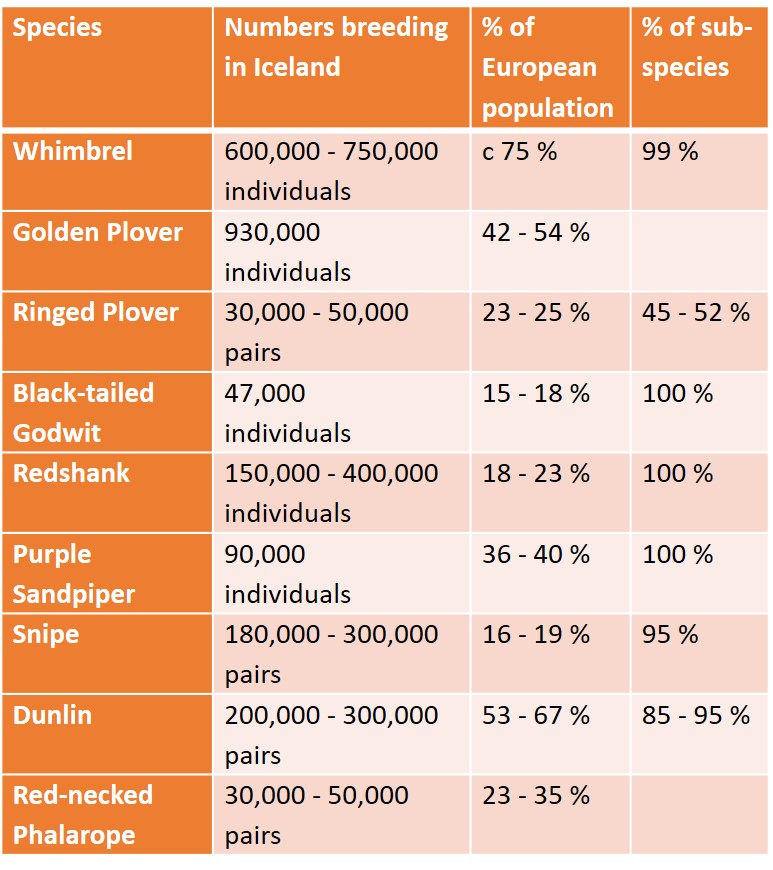

Iceland holds large proportions of the global nesting populations of Golden Plover (52%), Whimbrel (40%), Redshank (19%), Dunlin (16%) and Black-tailed godwit (10%) (see Gunnarsson et al 2006) and is home to half or more of Europe’s Dunlin, Golden Plover and Whimbrel. Data in the table alongside have been extracted from Annex 4 of the report, which was discussed at the 12th Standing Committee of AEWA (Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds) in Jan/Feb 2017.

Aldís measured the areas of 76 plantations in her study, using aerial photographs. The total area of woodland was about 2,800 ha and the total amount of semi-natural habitat in the surrounding 200 m was about 3,600 ha. Using the reduced densities that she found on the transects and the direct losses for the plantations themselves, she estimates potential losses of about 3000 breeding waders, just around these 76 forest plots. Extrapolating this figure to the whole of the Southern Lowlands of Iceland, the total losses resulting from all current plantations are likely to already be in the tens of thousands. Worryingly, the densities measured on the transects in this paper (even 700 m from forest edge) were well below those measured (slightly differently) in previous studies of completely open habitat, suggesting that losses may already be significantly higher than estimated in the paper.

A scary statistic in the paper is that “6.3% of the Icelandic lowlands is currently less than 200 m from forest plantations”. Given the incentives to plant lots more trees, this is particularly worrying for species such as Black-tailed Godwits, the vast majority of which breed in these lowland areas (between sea level and 300 metres).

It has been suggested that breeding waders might move elsewhere when impacted by forestry but migratory wader species are typically highly faithful to breeding sites. If birds are not going to move to accommodate trees, then perhaps plantations should be located where bird numbers are naturally low, such as in sparsely or non-vegetated areas, at higher altitudes and on slopes? Planning decisions could usefully be informed by surveys of breeding birds, to identify high-density areas that should be avoided.

The severe impact that planting forests in open landscapes can have on populations of ground-nesting birds emphasises the need for strategic planning of tree-planting schemes. Given Iceland’s statutory commitments to species protection, as a signatory to AEWA and the Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats, and the huge contribution of Iceland to global migratory bird flyways, these are challenges that must be addressed quickly, before we see population-level impacts throughout the European and West African Flyway.

To learn more

The take-home message from this work is clear. Local planning decisions and the ways in which forestry grants are allocated are producing a patchy distribution of plantations across the lowlands of Iceland, and this is bad news for breeding waders.

The paper at the heart of this blog is:

Subarctic afforestation: effects of forest plantations on ground-nesting birds in lowland Iceland. Aldís E. Pálsdóttir ,Jennifer A. Gill, José A. Alves, Snæbjörn Pálsson, Verónica Méndez, Harry Ewing & Tómas G. Gunnarsson. Journal of Applied Ecology.

Other WaderTales blogs that may be of interest:

Forest edges

- The edge effect of forests is discussed in work from Estonia by Triin Kaasiku (see Keep away from the trees). Here she looks at the outcomes of nests at different distances from forest edges.

- Do waders avoid nesting close to trees? This is discussed in Mastering Lapwing Conservation.

- The predator effect lingers long after forests are cleared, according to research described in Trees, predators and breeding waders.

Work by Aldís Pálsdóttir (pictured right)

- The WaderTales blog, Power lines and breeding waders, summarises Effects of overhead power-lines on the density of ground-nesting birds in open sub-arctic habitats.

- Further blogs about wader numbers close to roads and in the vicinity of summer cottages will be added when papers are published.

Changing agricultural systems in Iceland (work by Lilja Jóhannesdóttir)

- Do Iceland’s farmers care about wader conservation? At a time of agricultural expansion, are farmers prepared to leave space for breeding waders?

- Farming for waders in Iceland investigates densities of breeding waders along the gradient of agricultural intensification associated with farming activities.

- Designing wader landscapes investigates whether breeding densities of waders can be maintained, as farming expands and intensification increases.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton (@GrahamFAppleton) to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on published papers, with the aim of making shorebird science available to a broader audience.

There is nothing more obvious than an Oystercatcher sitting on his or her nest, but a brooding Snipe can be invisible until almost trodden upon. Which strategy works better: nesting in plain view but laying cryptically camouflaged eggs or hiding yourself and your nest in a clump of grass? Which species is most likely to hatch a successful brood of chicks and in what circumstances? In a

There is nothing more obvious than an Oystercatcher sitting on his or her nest, but a brooding Snipe can be invisible until almost trodden upon. Which strategy works better: nesting in plain view but laying cryptically camouflaged eggs or hiding yourself and your nest in a clump of grass? Which species is most likely to hatch a successful brood of chicks and in what circumstances? In a

As discussed in previous WaderTales blogs, particularly

As discussed in previous WaderTales blogs, particularly

As a volunteer taking part in the Breeding Bird Survey (BTO/JNCC/RSPB) in the UK, I feel that I do my bit to monitor what is happening to local bird population – providing counts that build into national trends. The work involved in delivering indices for breeding waders across the area of Fennoscandia shown in the map is in a different league. Here, counters visit habitats as diverse as forests, wetlands, mires and tundra, within the boreal and arctic areas of Norway, Sweden and Finland. Some survey sites are so remote that access requires the use of helicopters.

As a volunteer taking part in the Breeding Bird Survey (BTO/JNCC/RSPB) in the UK, I feel that I do my bit to monitor what is happening to local bird population – providing counts that build into national trends. The work involved in delivering indices for breeding waders across the area of Fennoscandia shown in the map is in a different league. Here, counters visit habitats as diverse as forests, wetlands, mires and tundra, within the boreal and arctic areas of Norway, Sweden and Finland. Some survey sites are so remote that access requires the use of helicopters.

Looking at the results from across Norway, Sweden & Finland:

Looking at the results from across Norway, Sweden & Finland:

Lapwing. The trends within the three Fennoscandian countries are very different. In Norway, there has been a dramatic decline (-15.2% per year during 2006–2018) and the Lapwing is now nearly extinct in many areas. The trend in Sweden is also significantly negative (-5.8% per year). In Finland, however, where the species is more widespread and numerous, there has been a strong increase (+5.9% per year) during the same period. See figure alongside.

Lapwing. The trends within the three Fennoscandian countries are very different. In Norway, there has been a dramatic decline (-15.2% per year during 2006–2018) and the Lapwing is now nearly extinct in many areas. The trend in Sweden is also significantly negative (-5.8% per year). In Finland, however, where the species is more widespread and numerous, there has been a strong increase (+5.9% per year) during the same period. See figure alongside.

Ruff. There were major declines in the period immediately prior to this review (

Ruff. There were major declines in the period immediately prior to this review (

Your task, should you choose to accept it, is to turn farmland into a haven for breeding waders. The only tools you have at your disposal are tractors and cows and we will give you permission to pump water out of nearby rivers when conditions allow. That’s how it started. These days the diggers look big enough to use on a motorway construction site!

Your task, should you choose to accept it, is to turn farmland into a haven for breeding waders. The only tools you have at your disposal are tractors and cows and we will give you permission to pump water out of nearby rivers when conditions allow. That’s how it started. These days the diggers look big enough to use on a motorway construction site!

The marshes of the Norfolk Broads have been drying out for 2000 years. By the 1970s, and after over 400 years of farming, the Halvergate Marsh complex was on the point of being fully drained and by 1985 much of the wet grassland in which waders formerly bred had already been lost and turned into arable fields. At this point, the RSPB made its first purchase of land, as they tried to retain at least some of the threatened habitat which is so important to winter wildfowl and summer waders. At the same time, campaigning by local and national conservationists secured legal protection for the unique Broadland scenery and the species that rely upon the habitats it contains, thereby halting the advance of the combine harvesters.

The marshes of the Norfolk Broads have been drying out for 2000 years. By the 1970s, and after over 400 years of farming, the Halvergate Marsh complex was on the point of being fully drained and by 1985 much of the wet grassland in which waders formerly bred had already been lost and turned into arable fields. At this point, the RSPB made its first purchase of land, as they tried to retain at least some of the threatened habitat which is so important to winter wildfowl and summer waders. At the same time, campaigning by local and national conservationists secured legal protection for the unique Broadland scenery and the species that rely upon the habitats it contains, thereby halting the advance of the combine harvesters.

By creating a hot-spot for nesting birds, within an intensively-farmed landscape, land-managers also produce a food-rich area for predators, attracted in by concentrations of eggs, chicks and sitting adults. Restricting the activities of species such as foxes and crows is an important part of the role of an RSPB warden, carried out through site management and active control measures. By focusing these activities in the winter period, the RSPB’s Halvergate Marshes team are able to stop corvids and foxes from setting up territories within the area that is managed for breeding waders. Electric fencing can help to prevent foxes moving onto the site in spring, while changing the way that core wader areas are managed helps to reduce fox/nest interactions by, for instance:

By creating a hot-spot for nesting birds, within an intensively-farmed landscape, land-managers also produce a food-rich area for predators, attracted in by concentrations of eggs, chicks and sitting adults. Restricting the activities of species such as foxes and crows is an important part of the role of an RSPB warden, carried out through site management and active control measures. By focusing these activities in the winter period, the RSPB’s Halvergate Marshes team are able to stop corvids and foxes from setting up territories within the area that is managed for breeding waders. Electric fencing can help to prevent foxes moving onto the site in spring, while changing the way that core wader areas are managed helps to reduce fox/nest interactions by, for instance: There is more about these measures in these blogs, with links to papers from the RSPB and University of East Anglia team of conservation researchers:

There is more about these measures in these blogs, with links to papers from the RSPB and University of East Anglia team of conservation researchers:

Redshank: The graph alongside illustrates how Redshank numbers have changed across the decades. At the same time as

Redshank: The graph alongside illustrates how Redshank numbers have changed across the decades. At the same time as

Lapwing: Between 1988 and 1998, the number of pairs of Lapwing rose from 14 to 79, reaching a peak of 157 in 2010. Numbers vary, according to spring weather and water levels, with between 83 and 130 pairs in the years 2011 to 2019. The national decline in England was 28% between 1995 and 2017 (Breeding Bird Survey) – not quite as drastic as for Redshank but still worrying. Intensive studies at Berney have shown that productivity is only high enough to boost numbers in some years. The latest project by UEA and RSPB conservation scientists involves trialling temporary electric fences to provide protection for first clutches and broods. Hopefully Berney can become a net exporter of Lapwings in most years.

Lapwing: Between 1988 and 1998, the number of pairs of Lapwing rose from 14 to 79, reaching a peak of 157 in 2010. Numbers vary, according to spring weather and water levels, with between 83 and 130 pairs in the years 2011 to 2019. The national decline in England was 28% between 1995 and 2017 (Breeding Bird Survey) – not quite as drastic as for Redshank but still worrying. Intensive studies at Berney have shown that productivity is only high enough to boost numbers in some years. The latest project by UEA and RSPB conservation scientists involves trialling temporary electric fences to provide protection for first clutches and broods. Hopefully Berney can become a net exporter of Lapwings in most years.

Working with Jen Smart, who was a Principal Conservation Scientist at the RSPB’s centre for Conservation, Mark has added a Dutch dimension to the RSPB’s advice work by co-authoring

Working with Jen Smart, who was a Principal Conservation Scientist at the RSPB’s centre for Conservation, Mark has added a Dutch dimension to the RSPB’s advice work by co-authoring

The new scrapes should not only attract wintering and breeding birds but also many passage waders, such as the Wood Sandpiper pictured to the right. The whole scheme has the potential to be another win-win-win-win, for the owners of low-lying properties, for Broadland farmers, for internationally important bird populations and for local and visiting birdwatchers.

The new scrapes should not only attract wintering and breeding birds but also many passage waders, such as the Wood Sandpiper pictured to the right. The whole scheme has the potential to be another win-win-win-win, for the owners of low-lying properties, for Broadland farmers, for internationally important bird populations and for local and visiting birdwatchers.

How many waders spend the winter in Great Britain? The answer is provided within an article in British Birds entitled

How many waders spend the winter in Great Britain? The answer is provided within an article in British Birds entitled  Population totals help to put annual percentage changes into context;

Population totals help to put annual percentage changes into context; For species of wader that also make use of the open coast, the Non-estuarine Waterbirds Survey of 2015/16 (or NEWS III) provided additional data, updating the NEWS II figures from 2006/07.

For species of wader that also make use of the open coast, the Non-estuarine Waterbirds Survey of 2015/16 (or NEWS III) provided additional data, updating the NEWS II figures from 2006/07. Great Britain is extremely important in the context of the East Atlantic Flyway, as is obvious from the fact that the area holds nearly five million waders. The WeBs counts already monitor the ups and downs on an annual basis but this review provides an opportunity to turn the percentages into actual numbers. It is concerning that, over a period representing less than a decade, the average maximum winter count for six of the species that were surveyed dropped by a total of over 150,000. These big losers were Knot, Oystercatcher, Redshank, Curlew, Grey Plover and Dunlin, ordered by number of birds lost, with Knot seeing the biggest absolute decline.

Great Britain is extremely important in the context of the East Atlantic Flyway, as is obvious from the fact that the area holds nearly five million waders. The WeBs counts already monitor the ups and downs on an annual basis but this review provides an opportunity to turn the percentages into actual numbers. It is concerning that, over a period representing less than a decade, the average maximum winter count for six of the species that were surveyed dropped by a total of over 150,000. These big losers were Knot, Oystercatcher, Redshank, Curlew, Grey Plover and Dunlin, ordered by number of birds lost, with Knot seeing the biggest absolute decline.

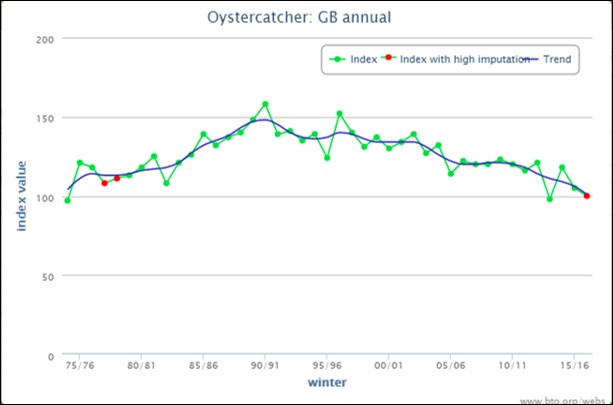

The drop in Oystercatcher numbers from 320,000 to 290,000 appears to be less than 10%, compared to a ten-year decline of 12% on WeBS. Improved analysis of NEWS data helped to add some more birds to the open-coast estimate so the 10% fall may underestimate the seriousness of the Oystercatcher situation. The 25-year Oystercatcher decline on WeBS is 26%, which is not surprising if you look at the changes to breeding numbers in Scotland, where most British birds are to be found. There’s more about this in:

The drop in Oystercatcher numbers from 320,000 to 290,000 appears to be less than 10%, compared to a ten-year decline of 12% on WeBS. Improved analysis of NEWS data helped to add some more birds to the open-coast estimate so the 10% fall may underestimate the seriousness of the Oystercatcher situation. The 25-year Oystercatcher decline on WeBS is 26%, which is not surprising if you look at the changes to breeding numbers in Scotland, where most British birds are to be found. There’s more about this in:  The Redshank decline of 26,000 is higher than would be predicted from WeBS figures, suggesting a drop of over 20% since APEP3, rather than ‘just’ 15% for the ten-year WeBS figure. This is a species that also features strongly in the Non-estuarine Waterbird Survey and that might explain the difference. Wintering Redshank are mostly of British and Icelandic origin, with the

The Redshank decline of 26,000 is higher than would be predicted from WeBS figures, suggesting a drop of over 20% since APEP3, rather than ‘just’ 15% for the ten-year WeBS figure. This is a species that also features strongly in the Non-estuarine Waterbird Survey and that might explain the difference. Wintering Redshank are mostly of British and Icelandic origin, with the  It has been suggested that the long-term declines of Grey Plover and Dunlin may be associated with short-stopping, with new generations of both species wintering closer to their eastern breeding grounds than used to be the case. WeBS results indicate a 31% drop in Grey Plover and a 42% drop in Dunlin, over the last 25 years. There was a loss of 10,000 for both species between APEP3 and the new review, representing declines of 23% and 3% respectively.

It has been suggested that the long-term declines of Grey Plover and Dunlin may be associated with short-stopping, with new generations of both species wintering closer to their eastern breeding grounds than used to be the case. WeBS results indicate a 31% drop in Grey Plover and a 42% drop in Dunlin, over the last 25 years. There was a loss of 10,000 for both species between APEP3 and the new review, representing declines of 23% and 3% respectively. One of the consequences of improved statistical techniques, as used this time around, is the apparent decline in the estimated population of Black-tailed Godwit. The new figure of 39,000 is 4,000 smaller than in APEP3, despite the fact that the WeBS graph clearly shows an increase. Interpolation using WeBs figures suggests that the earlier population estimate should have been 31,000, rather than 43,000.

One of the consequences of improved statistical techniques, as used this time around, is the apparent decline in the estimated population of Black-tailed Godwit. The new figure of 39,000 is 4,000 smaller than in APEP3, despite the fact that the WeBS graph clearly shows an increase. Interpolation using WeBs figures suggests that the earlier population estimate should have been 31,000, rather than 43,000. Snipe (Common): The winter estimate remains as 1,100,000 – a figure that was acknowledged in APEP3 as being less reliable than that of most species. At the same time, the GB breeding population was estimated as 76,000 pairs, indicating at least a 4:1 ratio of foreign to British birds, and that does not take account of the number of British birds that migrate south and west. Snipe are ‘amber listed’ but BBS suggests a recent increase of 26% (1995-2018). There is a WaderTales blog about

Snipe (Common): The winter estimate remains as 1,100,000 – a figure that was acknowledged in APEP3 as being less reliable than that of most species. At the same time, the GB breeding population was estimated as 76,000 pairs, indicating at least a 4:1 ratio of foreign to British birds, and that does not take account of the number of British birds that migrate south and west. Snipe are ‘amber listed’ but BBS suggests a recent increase of 26% (1995-2018). There is a WaderTales blog about  The paper in British Birds also includes a table of January population estimates, to provide data that are comparable to mid-winter counts in other countries. These figures are used in waterbird monitoring for the International Waterbird Census for the African Eurasian Flyway. The main table (and figures mentioned above) are average maximum winter counts (in the period September to March). Black-tailed Godwit is one species that illustrates the difference, with a mean of 30,000 in January and a mean peak count of 39,000. Having moulted in Great Britain, some Black-tailed Godwits move south to France and Portugal in late autumn, returning as early as February. January counts are therefore substantially lower than early-winter and late-winter counts. There is more about the migratory strategy employed by Black-tailed Godwits that winter in southern Europe in

The paper in British Birds also includes a table of January population estimates, to provide data that are comparable to mid-winter counts in other countries. These figures are used in waterbird monitoring for the International Waterbird Census for the African Eurasian Flyway. The main table (and figures mentioned above) are average maximum winter counts (in the period September to March). Black-tailed Godwit is one species that illustrates the difference, with a mean of 30,000 in January and a mean peak count of 39,000. Having moulted in Great Britain, some Black-tailed Godwits move south to France and Portugal in late autumn, returning as early as February. January counts are therefore substantially lower than early-winter and late-winter counts. There is more about the migratory strategy employed by Black-tailed Godwits that winter in southern Europe in  The authors have done a tremendous job. They have refined the way that estimates are calculated, they have combined the results from WeBS and NEWS III, and they have delivered population estimates for 25 wader species and many more other species of waterbirds. These population estimates will be used in conservation decision-making until the next set of numbers becomes available. Meanwhile, thousands of birdwatchers will count the birds on their WeBS patches in each winter month, every year. Without them, this paper could not have been written.

The authors have done a tremendous job. They have refined the way that estimates are calculated, they have combined the results from WeBS and NEWS III, and they have delivered population estimates for 25 wader species and many more other species of waterbirds. These population estimates will be used in conservation decision-making until the next set of numbers becomes available. Meanwhile, thousands of birdwatchers will count the birds on their WeBS patches in each winter month, every year. Without them, this paper could not have been written.

Northern Ireland is a great place for wintering waders but the same can no longer be said for its breeding species. There are far too few places left in which Curlew bubble and Snipe drum.

Northern Ireland is a great place for wintering waders but the same can no longer be said for its breeding species. There are far too few places left in which Curlew bubble and Snipe drum. We know that there were some great wader hot-spots in the years 1985 to 1987, when a major Northern Ireland survey took place, and that large drops in numbers were reported in 1999 and again in 2013, after other dedicated surveys, but what is happening now? Are there still places where Snipe drum and Curlew bubble? In 2019, the BTO in Northern Ireland asked local and visiting birdwatchers to revisit some of the best places that were identified in previous surveys, to look for breeding waders and to assess the habitats that remain. This work complemented work undertaken by RSPB Northern Ireland during the same period.

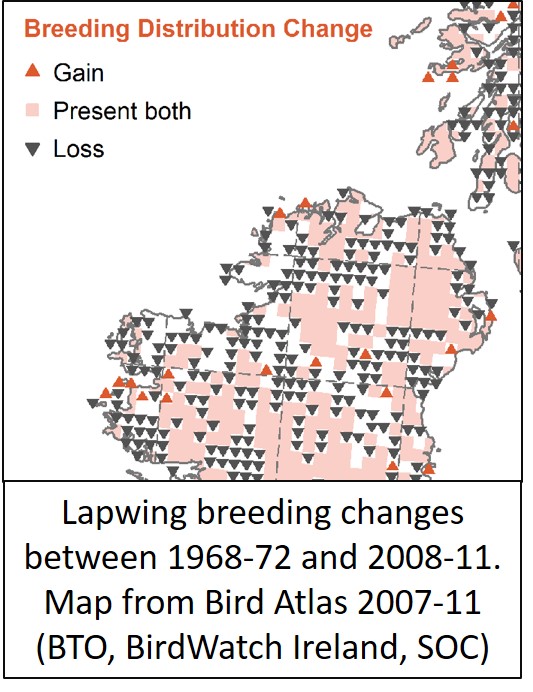

We know that there were some great wader hot-spots in the years 1985 to 1987, when a major Northern Ireland survey took place, and that large drops in numbers were reported in 1999 and again in 2013, after other dedicated surveys, but what is happening now? Are there still places where Snipe drum and Curlew bubble? In 2019, the BTO in Northern Ireland asked local and visiting birdwatchers to revisit some of the best places that were identified in previous surveys, to look for breeding waders and to assess the habitats that remain. This work complemented work undertaken by RSPB Northern Ireland during the same period. The Lapwing has quietly disappeared from much of Northern Ireland over the last fifty years. The black triangles in the map alongside represent 10-km squares that lost their breeding Lapwings between the two atlases of 1968-72 and 2008-11. Previous Northern Ireland surveys of breeding waders in 1985-87 and 2013 suggest that the number of pairs dropped from an estimated total of 5250 to a total of 860 – that’s a loss of 5 out of 6 pairs.

The Lapwing has quietly disappeared from much of Northern Ireland over the last fifty years. The black triangles in the map alongside represent 10-km squares that lost their breeding Lapwings between the two atlases of 1968-72 and 2008-11. Previous Northern Ireland surveys of breeding waders in 1985-87 and 2013 suggest that the number of pairs dropped from an estimated total of 5250 to a total of 860 – that’s a loss of 5 out of 6 pairs. There is no recent estimate for the number of breeding Redshank in Northern Ireland. Across the UK, the

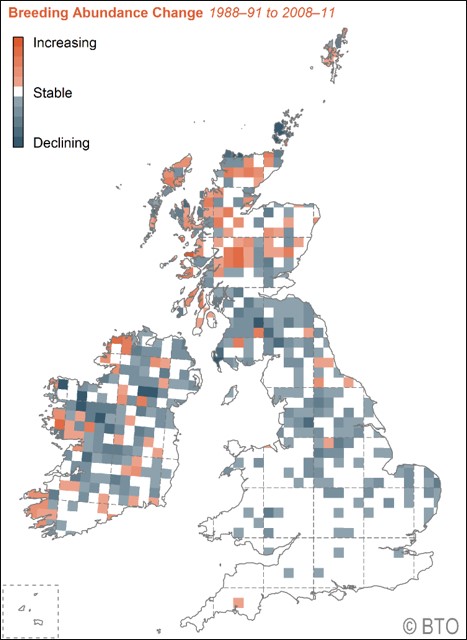

There is no recent estimate for the number of breeding Redshank in Northern Ireland. Across the UK, the  The lowland wader survey in 1985-87 suggested that the Northern Ireland population of Snipe was about 5725 pairs. By the time of the next survey in 1999, that number had dropped to 3993 and then to 1123 in 2013. That’s a drop of 80%. Snipe seem very sensitive to habitat change, especially drainage. The map alongside shows the change in abundance between 1988-91 and 2008-11 across Britain & Ireland. There is an interesting mix of losses (grey) and increases (orange) in Northern Ireland. It would have been great if the 2019 survey has picked up some new Snipe hot-spots. Sadly, in line with other waders, the number of pairs in key sites dropped by 71% between 1985–87 and 2018–19.

The lowland wader survey in 1985-87 suggested that the Northern Ireland population of Snipe was about 5725 pairs. By the time of the next survey in 1999, that number had dropped to 3993 and then to 1123 in 2013. That’s a drop of 80%. Snipe seem very sensitive to habitat change, especially drainage. The map alongside shows the change in abundance between 1988-91 and 2008-11 across Britain & Ireland. There is an interesting mix of losses (grey) and increases (orange) in Northern Ireland. It would have been great if the 2019 survey has picked up some new Snipe hot-spots. Sadly, in line with other waders, the number of pairs in key sites dropped by 71% between 1985–87 and 2018–19. There’s a WaderTales blog about

There’s a WaderTales blog about

Flocks of young birds are found on estuaries in the summer, as Oystercatchers typically don’t breed until three years old. We know that the number of breeding Oystercatchers in Scotland dropped by 39% between 1994 and 2018 but English numbers rose by 49% (

Flocks of young birds are found on estuaries in the summer, as Oystercatchers typically don’t breed until three years old. We know that the number of breeding Oystercatchers in Scotland dropped by 39% between 1994 and 2018 but English numbers rose by 49% ( Golden Plover: Ireland is a winter destination of choice for many Golden Plover that breed in Iceland. The recovery of a Belgian-ringed bird in 2006 suggests that some birds may arrive from the east as well. Wintering numbers are half what they were 25 years ago, according to WeBS data for Northern Ireland. A few breeding birds can still be found in the western parts of Northern Ireland but they have been lost from most other areas.

Golden Plover: Ireland is a winter destination of choice for many Golden Plover that breed in Iceland. The recovery of a Belgian-ringed bird in 2006 suggests that some birds may arrive from the east as well. Wintering numbers are half what they were 25 years ago, according to WeBS data for Northern Ireland. A few breeding birds can still be found in the western parts of Northern Ireland but they have been lost from most other areas.

Woodcock: The black triangles in the map opposite show the parts of Northern Ireland that have lost breeding Woodcock in the last 50 years. Data are from Bird Atlas 2007-11 (BTO, BirdWatch Ireland & SOC). In late autumn, birds fly in from counties such as Germany, Norway and Russia.

Woodcock: The black triangles in the map opposite show the parts of Northern Ireland that have lost breeding Woodcock in the last 50 years. Data are from Bird Atlas 2007-11 (BTO, BirdWatch Ireland & SOC). In late autumn, birds fly in from counties such as Germany, Norway and Russia.

Sites were located in five broad areas :

Sites were located in five broad areas :

Much has been written about the negative impacts of agriculture on breeding birds – but farming can be good for some species. In Iceland, where high-input agriculture is relatively recent, breeding waders are commonly found in nutrient-rich environments that are associated with increased production. How can high breeding densities of waders be maintained, as farming continues to expand and intensification increases?

Much has been written about the negative impacts of agriculture on breeding birds – but farming can be good for some species. In Iceland, where high-input agriculture is relatively recent, breeding waders are commonly found in nutrient-rich environments that are associated with increased production. How can high breeding densities of waders be maintained, as farming continues to expand and intensification increases?  Two previous WaderTales blogs have already shown that:

Two previous WaderTales blogs have already shown that: Globally, the expansion and intensification of agriculture has altered landscapes and the associated homogenisation has greatly influenced bird abundance and reduced biodiversity. Populations of numerous species, particularly specialist species, have declined, as agriculture has expanded, while generalist species have often thrived in agricultural habitats.

Globally, the expansion and intensification of agriculture has altered landscapes and the associated homogenisation has greatly influenced bird abundance and reduced biodiversity. Populations of numerous species, particularly specialist species, have declined, as agriculture has expanded, while generalist species have often thrived in agricultural habitats. Although there are some areas of Iceland in which farming is quite intensive, there are many others where farmers have a lighter touch. For instance, nutrient-poor dwarf birch marshes may occasionally be grazed by sheep in the summer but these areas have never received applications of artificial fertiliser. At this end of the intensification continuum, increasing agricultural operations may have benefits for breeding waders. When a patch of rough grazing is ploughed and turned into a hay meadow, the addition of fertilisers can potentially increase soil fertility and create an attractive place for waders to feed. A hay meadow within a local area that is dominated by dwarf birch marsh could effectively increase the heterogeneity (& nutrient-richness via spill-over) of the local area, albeit in an artificial way. In the UK, Golden Plovers breeding on moorland are known to travel up to 7 km to feed on fertilised hayfields with high earthworm densities. This

Although there are some areas of Iceland in which farming is quite intensive, there are many others where farmers have a lighter touch. For instance, nutrient-poor dwarf birch marshes may occasionally be grazed by sheep in the summer but these areas have never received applications of artificial fertiliser. At this end of the intensification continuum, increasing agricultural operations may have benefits for breeding waders. When a patch of rough grazing is ploughed and turned into a hay meadow, the addition of fertilisers can potentially increase soil fertility and create an attractive place for waders to feed. A hay meadow within a local area that is dominated by dwarf birch marsh could effectively increase the heterogeneity (& nutrient-richness via spill-over) of the local area, albeit in an artificial way. In the UK, Golden Plovers breeding on moorland are known to travel up to 7 km to feed on fertilised hayfields with high earthworm densities. This  Lilja’s work in the Southern Lowlands of Iceland focused upon understanding how agriculture influences breeding wader densities and how these relationships might influence future change. At its heart were counts of adult waders encountered along 200 transects (totalling over 100 kilometres) within semi-natural habitats, visited at several stages during the breeding seasons of 2011 and 2012.

Lilja’s work in the Southern Lowlands of Iceland focused upon understanding how agriculture influences breeding wader densities and how these relationships might influence future change. At its heart were counts of adult waders encountered along 200 transects (totalling over 100 kilometres) within semi-natural habitats, visited at several stages during the breeding seasons of 2011 and 2012.

Using data collected from these 200 lowland transects, Lilja was able to establish relationships between breeding wader densities and the amount of cultivated land and wetland in the surrounding landscape. These two habitat types were considered because future agricultural expansion is likely to take place on drained wetlands that have high conservation value. In her analyses she assessed the extent to which the amount of cultivated land in the surrounding landscape affects wader densities on semi-natural land, and then considered the potential effects of future agricultural expansion on wader populations. There was substantial variation in the density of all of the six most common wader species recorded on the transects, ranging from 0 to 284 birds/km2.

Using data collected from these 200 lowland transects, Lilja was able to establish relationships between breeding wader densities and the amount of cultivated land and wetland in the surrounding landscape. These two habitat types were considered because future agricultural expansion is likely to take place on drained wetlands that have high conservation value. In her analyses she assessed the extent to which the amount of cultivated land in the surrounding landscape affects wader densities on semi-natural land, and then considered the potential effects of future agricultural expansion on wader populations. There was substantial variation in the density of all of the six most common wader species recorded on the transects, ranging from 0 to 284 birds/km2. The relationships between the areas of wetland and agriculture in the surrounding landscape and the density of waders vary between species, as you can read in some detail in the paper. A few highlights are:

The relationships between the areas of wetland and agriculture in the surrounding landscape and the density of waders vary between species, as you can read in some detail in the paper. A few highlights are:

Given the international importance of Iceland as a home for breeding waders it would be nice to think that this paper can be used to develop national land management policies that can prevent the unintended loss of species such as Golden Plover and Snipe, which landowners value and wish to preserve. At the farm and community level, the paper highlights the key importance of maintaining the complex and heterogeneous landscapes of lowland Iceland, retaining as many as possible of the remaining wetland patches and pockets of semi-natural land within even the most intensive of farming areas.

Given the international importance of Iceland as a home for breeding waders it would be nice to think that this paper can be used to develop national land management policies that can prevent the unintended loss of species such as Golden Plover and Snipe, which landowners value and wish to preserve. At the farm and community level, the paper highlights the key importance of maintaining the complex and heterogeneous landscapes of lowland Iceland, retaining as many as possible of the remaining wetland patches and pockets of semi-natural land within even the most intensive of farming areas. This paper provides a useful reminder that the links between land use changes and biodiversity implications can be highly context-dependent. Further agricultural conversion of wetlands and rough grazing areas in the fertile low-lying areas of Iceland is likely to be detrimental for breeding waders, but such effects may be less apparent in less fertile, higher altitude areas. Here, the conversion of some land from rough-grazing to hay meadows may provide feeding opportunities off-territory for Dunlin, Golden Plover and Whimbrel. The scale at which the addition of cultivated areas is beneficial to breeding waders has yet to be determined.

This paper provides a useful reminder that the links between land use changes and biodiversity implications can be highly context-dependent. Further agricultural conversion of wetlands and rough grazing areas in the fertile low-lying areas of Iceland is likely to be detrimental for breeding waders, but such effects may be less apparent in less fertile, higher altitude areas. Here, the conversion of some land from rough-grazing to hay meadows may provide feeding opportunities off-territory for Dunlin, Golden Plover and Whimbrel. The scale at which the addition of cultivated areas is beneficial to breeding waders has yet to be determined.

* BBS results for Snipe for 1995-2017 revise the change figure to show an increase of 32%.

* BBS results for Snipe for 1995-2017 revise the change figure to show an increase of 32%. * BBS results for Lapwing for 1995-2017 revise the change figure to show a decrease of 55%.

* BBS results for Lapwing for 1995-2017 revise the change figure to show a decrease of 55%. * BBS results for Curlew for 1995-2017 revise the change figure to show a decrease of 61%.

* BBS results for Curlew for 1995-2017 revise the change figure to show a decrease of 61%.

Oystercatcher down 44% *

Oystercatcher down 44% * Pearce-Higgins, J.W., Yalden, D.W. & Whittingham, M.J. 2005.

Pearce-Higgins, J.W., Yalden, D.W. & Whittingham, M.J. 2005.

In Iceland, volcanic activity poses serious short-term threats to agriculture, especially in areas close to the mid-Atlantic ridge, which runs through the island from south-west to north-east. Threats from volcanoes include ash-fall, lava, flooding of glacial rivers and earthquakes but, on the plus side, nutritional inputs from volcanoes have beneficial effects on soil fertility in these central areas. Over time, and with the assistance of wind and water, many of these nutrients collect in the lowlands of the country – the areas that now form the main agricultural areas, especially in the warmer south.

In Iceland, volcanic activity poses serious short-term threats to agriculture, especially in areas close to the mid-Atlantic ridge, which runs through the island from south-west to north-east. Threats from volcanoes include ash-fall, lava, flooding of glacial rivers and earthquakes but, on the plus side, nutritional inputs from volcanoes have beneficial effects on soil fertility in these central areas. Over time, and with the assistance of wind and water, many of these nutrients collect in the lowlands of the country – the areas that now form the main agricultural areas, especially in the warmer south.

Large numbers of waders were encountered in all transects in all parts of Iceland, with Black-tailed Godwit and Redshank contributing most records. There were also important numbers of Oystercatcher, Golden Plover, Dunlin, Snipe and Whimbrel. Overall, wader densities on farms did not vary significantly between regions or between early and late visits but there were some subtle differences:

Large numbers of waders were encountered in all transects in all parts of Iceland, with Black-tailed Godwit and Redshank contributing most records. There were also important numbers of Oystercatcher, Golden Plover, Dunlin, Snipe and Whimbrel. Overall, wader densities on farms did not vary significantly between regions or between early and late visits but there were some subtle differences: One of the interesting differences in the west was the redistribution of Redshank as the season progressed. There were three times as many pairs of Redshank in cultivated land during the chick-rearing period than during incubation, suggesting that adults may be moving broods into cultivated land. Resources for chicks may well be relatively more abundant or accessible in these areas, given the relatively low levels of nutrients in areas that are a long way from the active volcano belt. There’s also a suggestion that drainage ditches around cultivated fields in the west may provide important resources for Snipe.

One of the interesting differences in the west was the redistribution of Redshank as the season progressed. There were three times as many pairs of Redshank in cultivated land during the chick-rearing period than during incubation, suggesting that adults may be moving broods into cultivated land. Resources for chicks may well be relatively more abundant or accessible in these areas, given the relatively low levels of nutrients in areas that are a long way from the active volcano belt. There’s also a suggestion that drainage ditches around cultivated fields in the west may provide important resources for Snipe.

It is estimated that between 4 and 5 million waders leave Iceland each autumn, for Europe, Africa and the South Pacific (Red-necked Phalarope). Iceland’s farmland supports many of these birds and this study highlights the need to protect them from the agricultural developments that have led to widespread wader losses throughout most of the world.

It is estimated that between 4 and 5 million waders leave Iceland each autumn, for Europe, Africa and the South Pacific (Red-necked Phalarope). Iceland’s farmland supports many of these birds and this study highlights the need to protect them from the agricultural developments that have led to widespread wader losses throughout most of the world.