The Sado Estuary is one of Portugal’s most important wetlands – a key link in the chain of sites connecting Africa and the Arctic, on the East Atlantic Flyway. In a paper in Waterbirds, João Belo and colleagues analyse changes in numbers of waders wintering in this estuary over the period 2010 to 2019, with a focus on roost sites. These results are interpreted in regional and flyway contexts. The team find serious declines in numbers of Avocet, Dunlin and Ringed Plover.

Lost roost sites

The Sado Estuary became a nature reserve in 1980 and has since been classified as a Ramsar Site, a Special Protection Area (SPA – Natura 2000) and an Important Bird and Biodiversity Area. The Estuary lies about 30 km south of the much larger and more famous Tagus (or Tejo) Estuary, which is threatened by a new international airport (see Tagus Estuary: for birds or planes?). A suggestion that the Sado could provide mitigation habitat for damage done to the Tagus prompted scientists from the Universities of Aveiro and Lisbon to review the current state of the estuary.

João Belo and his colleagues used monthly data from a programme of wader surveys, conducted largely by volunteer birdwatchers. These took place between January 2010 and December 2019. Roosting birds were counted at high tide along the northern shores of the Sado estuary and any habitat changes were noted.

During the ten-year survey period, 21% of the available high-tide roost area was lost. These changes were associated with the commercial abandonment of saltpans (with consequent increases in vegetation) and the conversion of others for fish farming (often with netting, to keep out fish-eating birds).

Results of the survey

In their paper, João Belo and colleagues focused on total numbers of waders and counts of the six most commonly-encountered species: Avocet, Dunlin, Black-tailed Godwit, Redshank, Ringed Plover and Grey Plover. They compared winter (Dec, Jan and Feb) counts in 2019 with those from 2010. This is when peak numbers of Avocet, Redshank and Grey Plover occur. Higher counts of Dunlin are made in spring, as schinzii birds returned from Africa, with peak counts of Black-tailed Godwit and Ringed Plover occurring in autumn.

The key findings are:

- There was a strong decrease in the overall number of waders wintering in the Sado Estuary. This trend is mostly driven by steep declines in three of the six most abundant species: Avocet, Dunlin and Ringed Plover.

- Avocet numbers were 42% lower in 2019 than they had been in 2010.

- Dunlin numbers dropped by over half, with 2019 counts being only 47% of those in 2010. These are mostly dunlin of the alpina subspeciesthat breed between Northern Scandinavia and Siberia.

- Ringed Plover numbers dropped by 23% between 2010 and 2019.

- Redshank increased significantly between 2010 and 2019, while the population of Grey Plover was relatively stable, and it was not possible to derive a population trend for Black-tailed Godwit.

It is interesting to look at these patterns alongside data collected in Britain & Ireland, over the same period. As discussed in Do population estimates matter? and Ireland’s wintering waders, there have been major changes in wader numbers, with most species currently in decline.

- Winter Avocet numbers have increased massively in Britain & Ireland. It is possible that young birds are more easily able to settle in these northern areas, now that winter temperatures are generally warmer. Declines in Portugal may reflect a northwards shift of the winter population, driven by new generations of birds.

- Numbers of Ringed Plovers in Britain & Ireland did not change over the period 2010 to 2019 but had dropped a lot in the preceding twenty years.

- For Dunlin, the size of the declines in Britain & Ireland are consistent with those on the Sado. It has been suggested that more young birds might be settling in areas such as the Wadden Sea, closer to Siberian breeding areas, something that may have become more possible given the reduced intensity and occurrence of freezing conditions along the east coast of the North Sea.

Regional and Flyway patterns

As discussed in the blog Interpreting changing wader counts, based on research led by Verónica Méndez, local changes in numbers are usually reflective of broader changes in population levels. Individual waders are unlikely to seek alternative wintering sites unless habitat is removed, so birds do not re-assort themselves into the ‘best’ areas when population levels decrease. Instead, there is general thinning out across all sites as populations decline. In this context, it is unsurprising that the trends in the Sado Estuary are similar to those found elsewhere in Portugal and in other Western European wintering areas.

Looking forwards

The survey data collected between 2010 and 2019 form a useful backdrop against which to monitor what might happen when (or perhaps if) a new international airport is constructed within the nearby Tagus Estuary. If some birds are displaced to the Sado, increases in numbers might be expected.

Displacement is not cost-free, as has been shown in a well-studied population of Redshanks on the Severn Estuary in Wales. When Cardiff Bay was permanently flooded, as part of a major redevelopment, colour-marked Redshank dispersed to sites up to 19 km away. Adult birds that moved to new sites had difficulty maintaining body condition in the first winter following the closure of Cardiff Bay, unlike the Redshank that were already living in these sites. Their survival rates in subsequent winters continued to be lower than for ‘local’ birds, indicating longer-term effects than might have been predicted.

These three papers are essential reading for anyone interested in the consequences of displacements caused by development projects.

- Burton, N.H.K. 2000. Winter site-fidelity and survival of Redshank at Cardiff, South Wales. Bird Study 47: 102–112.

- Burton, N.H.K. & Armitage, M.J.S. 2005. Differences in the diurnal and nocturnal use of intertidal feeding grounds by Redshank. Bird Study 52: 120-128.

- Burton, N.H.K., Rehfisch, M.M., Clark, N.A. & Dodd, S.G. 2006. Impacts of sudden winter habitat loss on the body condition and survival of Redshank. Journal of Applied Ecology 43: 464-473

Given that the Sado has multiple conservation designations, including as a Ramsar site, and that this study has shown a clear loss of available roosting areas, perhaps it is time to identify a high-tide refuge that can be fully protected and managed in ways which create a range of suitable habitats for use by long-legged and short-legged waders. A nature reserve such as this has a potential to attract birdwatchers too, with prospective increased income from tourism.

Sado International

Curlews don’t get a mention in this paper but the The Sado provides a neat link to a 2022 blog, A Norfolk Curlew’s Summer. This tale focuses on ‘Bowie’, a male Curlew that breeds in Breckland (Eastern England) and has been tracked to The Sado Estuary. In the blog, Bowie’s story stops in The Tagus but he subsequently headed further south to The Sado, where he spent the winter. At the time of writing (13 Feb 2023) he is still there but hopefully he will heading north soon.

The Sado is not only important in the winter, of course. As mentioned earlier, it is a spring stop-over for birds such as schinzii Dunlin, heading north from Africa to Siberia, and a moulting/staging site for waders heading south in late summer. Tracking and colour-ringing are telling more of these stories, with links to countries as far north as Canada and Siberia and as far south as South Africa.

Keep counting

The Sado story could not have been written without the work of volunteer counters who collect monthly data during the winter months, on the Sado Estuary, across Portugal and on the wider East Atlantic Flyway. These monitoring efforts are essential when attempting to track changes in wader populations, especially when extra information can indicate links to habitat changes, as is the case in the Sado. The international picture is painted using Flyway information generated using January counts that are developed by the Institute for Nature Conservation and Forests (ICNF).

Here is a link to the paper:

Synchronous declines of wintering waders and high-tide roost area in a temperate estuary: results of a 10-year monitoring programme. João R. Belo, Maria P. Dias, João Jara, Amélia Almeida, Frederico Morais, Carlos Silva, Joaquim Valadeiro & José A. Alves. Waterbirds. doi.org/10.1675/063.045.0204

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton (@GrahamFAppleton) to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on published papers, with the aim of making shorebird science available to a broader audience.

Your task, should you choose to accept it, is to turn farmland into a haven for breeding waders. The only tools you have at your disposal are tractors and cows and we will give you permission to pump water out of nearby rivers when conditions allow. That’s how it started. These days the diggers look big enough to use on a motorway construction site!

Your task, should you choose to accept it, is to turn farmland into a haven for breeding waders. The only tools you have at your disposal are tractors and cows and we will give you permission to pump water out of nearby rivers when conditions allow. That’s how it started. These days the diggers look big enough to use on a motorway construction site!

The marshes of the Norfolk Broads have been drying out for 2000 years. By the 1970s, and after over 400 years of farming, the Halvergate Marsh complex was on the point of being fully drained and by 1985 much of the wet grassland in which waders formerly bred had already been lost and turned into arable fields. At this point, the RSPB made its first purchase of land, as they tried to retain at least some of the threatened habitat which is so important to winter wildfowl and summer waders. At the same time, campaigning by local and national conservationists secured legal protection for the unique Broadland scenery and the species that rely upon the habitats it contains, thereby halting the advance of the combine harvesters.

The marshes of the Norfolk Broads have been drying out for 2000 years. By the 1970s, and after over 400 years of farming, the Halvergate Marsh complex was on the point of being fully drained and by 1985 much of the wet grassland in which waders formerly bred had already been lost and turned into arable fields. At this point, the RSPB made its first purchase of land, as they tried to retain at least some of the threatened habitat which is so important to winter wildfowl and summer waders. At the same time, campaigning by local and national conservationists secured legal protection for the unique Broadland scenery and the species that rely upon the habitats it contains, thereby halting the advance of the combine harvesters.

By creating a hot-spot for nesting birds, within an intensively-farmed landscape, land-managers also produce a food-rich area for predators, attracted in by concentrations of eggs, chicks and sitting adults. Restricting the activities of species such as foxes and crows is an important part of the role of an RSPB warden, carried out through site management and active control measures. By focusing these activities in the winter period, the RSPB’s Halvergate Marshes team are able to stop corvids and foxes from setting up territories within the area that is managed for breeding waders. Electric fencing can help to prevent foxes moving onto the site in spring, while changing the way that core wader areas are managed helps to reduce fox/nest interactions by, for instance:

By creating a hot-spot for nesting birds, within an intensively-farmed landscape, land-managers also produce a food-rich area for predators, attracted in by concentrations of eggs, chicks and sitting adults. Restricting the activities of species such as foxes and crows is an important part of the role of an RSPB warden, carried out through site management and active control measures. By focusing these activities in the winter period, the RSPB’s Halvergate Marshes team are able to stop corvids and foxes from setting up territories within the area that is managed for breeding waders. Electric fencing can help to prevent foxes moving onto the site in spring, while changing the way that core wader areas are managed helps to reduce fox/nest interactions by, for instance: There is more about these measures in these blogs, with links to papers from the RSPB and University of East Anglia team of conservation researchers:

There is more about these measures in these blogs, with links to papers from the RSPB and University of East Anglia team of conservation researchers:

Redshank: The graph alongside illustrates how Redshank numbers have changed across the decades. At the same time as

Redshank: The graph alongside illustrates how Redshank numbers have changed across the decades. At the same time as

Lapwing: Between 1988 and 1998, the number of pairs of Lapwing rose from 14 to 79, reaching a peak of 157 in 2010. Numbers vary, according to spring weather and water levels, with between 83 and 130 pairs in the years 2011 to 2019. The national decline in England was 28% between 1995 and 2017 (Breeding Bird Survey) – not quite as drastic as for Redshank but still worrying. Intensive studies at Berney have shown that productivity is only high enough to boost numbers in some years. The latest project by UEA and RSPB conservation scientists involves trialling temporary electric fences to provide protection for first clutches and broods. Hopefully Berney can become a net exporter of Lapwings in most years.

Lapwing: Between 1988 and 1998, the number of pairs of Lapwing rose from 14 to 79, reaching a peak of 157 in 2010. Numbers vary, according to spring weather and water levels, with between 83 and 130 pairs in the years 2011 to 2019. The national decline in England was 28% between 1995 and 2017 (Breeding Bird Survey) – not quite as drastic as for Redshank but still worrying. Intensive studies at Berney have shown that productivity is only high enough to boost numbers in some years. The latest project by UEA and RSPB conservation scientists involves trialling temporary electric fences to provide protection for first clutches and broods. Hopefully Berney can become a net exporter of Lapwings in most years.

Working with Jen Smart, who was a Principal Conservation Scientist at the RSPB’s centre for Conservation, Mark has added a Dutch dimension to the RSPB’s advice work by co-authoring

Working with Jen Smart, who was a Principal Conservation Scientist at the RSPB’s centre for Conservation, Mark has added a Dutch dimension to the RSPB’s advice work by co-authoring

The new scrapes should not only attract wintering and breeding birds but also many passage waders, such as the Wood Sandpiper pictured to the right. The whole scheme has the potential to be another win-win-win-win, for the owners of low-lying properties, for Broadland farmers, for internationally important bird populations and for local and visiting birdwatchers.

The new scrapes should not only attract wintering and breeding birds but also many passage waders, such as the Wood Sandpiper pictured to the right. The whole scheme has the potential to be another win-win-win-win, for the owners of low-lying properties, for Broadland farmers, for internationally important bird populations and for local and visiting birdwatchers.

How many waders spend the winter in Great Britain? The answer is provided within an article in British Birds entitled

How many waders spend the winter in Great Britain? The answer is provided within an article in British Birds entitled  Population totals help to put annual percentage changes into context;

Population totals help to put annual percentage changes into context; For species of wader that also make use of the open coast, the Non-estuarine Waterbirds Survey of 2015/16 (or NEWS III) provided additional data, updating the NEWS II figures from 2006/07.

For species of wader that also make use of the open coast, the Non-estuarine Waterbirds Survey of 2015/16 (or NEWS III) provided additional data, updating the NEWS II figures from 2006/07. Great Britain is extremely important in the context of the East Atlantic Flyway, as is obvious from the fact that the area holds nearly five million waders. The WeBs counts already monitor the ups and downs on an annual basis but this review provides an opportunity to turn the percentages into actual numbers. It is concerning that, over a period representing less than a decade, the average maximum winter count for six of the species that were surveyed dropped by a total of over 150,000. These big losers were Knot, Oystercatcher, Redshank, Curlew, Grey Plover and Dunlin, ordered by number of birds lost, with Knot seeing the biggest absolute decline.

Great Britain is extremely important in the context of the East Atlantic Flyway, as is obvious from the fact that the area holds nearly five million waders. The WeBs counts already monitor the ups and downs on an annual basis but this review provides an opportunity to turn the percentages into actual numbers. It is concerning that, over a period representing less than a decade, the average maximum winter count for six of the species that were surveyed dropped by a total of over 150,000. These big losers were Knot, Oystercatcher, Redshank, Curlew, Grey Plover and Dunlin, ordered by number of birds lost, with Knot seeing the biggest absolute decline.

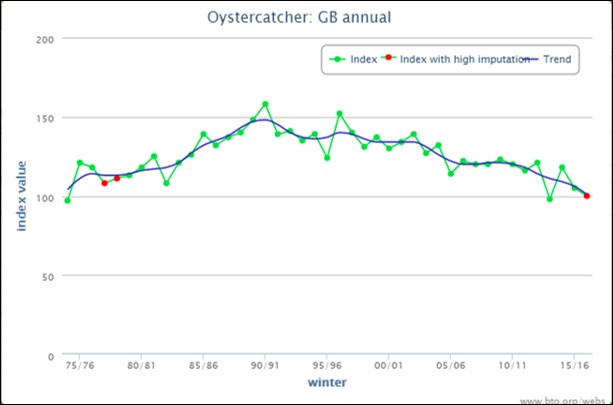

The drop in Oystercatcher numbers from 320,000 to 290,000 appears to be less than 10%, compared to a ten-year decline of 12% on WeBS. Improved analysis of NEWS data helped to add some more birds to the open-coast estimate so the 10% fall may underestimate the seriousness of the Oystercatcher situation. The 25-year Oystercatcher decline on WeBS is 26%, which is not surprising if you look at the changes to breeding numbers in Scotland, where most British birds are to be found. There’s more about this in:

The drop in Oystercatcher numbers from 320,000 to 290,000 appears to be less than 10%, compared to a ten-year decline of 12% on WeBS. Improved analysis of NEWS data helped to add some more birds to the open-coast estimate so the 10% fall may underestimate the seriousness of the Oystercatcher situation. The 25-year Oystercatcher decline on WeBS is 26%, which is not surprising if you look at the changes to breeding numbers in Scotland, where most British birds are to be found. There’s more about this in:  The Redshank decline of 26,000 is higher than would be predicted from WeBS figures, suggesting a drop of over 20% since APEP3, rather than ‘just’ 15% for the ten-year WeBS figure. This is a species that also features strongly in the Non-estuarine Waterbird Survey and that might explain the difference. Wintering Redshank are mostly of British and Icelandic origin, with the

The Redshank decline of 26,000 is higher than would be predicted from WeBS figures, suggesting a drop of over 20% since APEP3, rather than ‘just’ 15% for the ten-year WeBS figure. This is a species that also features strongly in the Non-estuarine Waterbird Survey and that might explain the difference. Wintering Redshank are mostly of British and Icelandic origin, with the  It has been suggested that the long-term declines of Grey Plover and Dunlin may be associated with short-stopping, with new generations of both species wintering closer to their eastern breeding grounds than used to be the case. WeBS results indicate a 31% drop in Grey Plover and a 42% drop in Dunlin, over the last 25 years. There was a loss of 10,000 for both species between APEP3 and the new review, representing declines of 23% and 3% respectively.

It has been suggested that the long-term declines of Grey Plover and Dunlin may be associated with short-stopping, with new generations of both species wintering closer to their eastern breeding grounds than used to be the case. WeBS results indicate a 31% drop in Grey Plover and a 42% drop in Dunlin, over the last 25 years. There was a loss of 10,000 for both species between APEP3 and the new review, representing declines of 23% and 3% respectively. One of the consequences of improved statistical techniques, as used this time around, is the apparent decline in the estimated population of Black-tailed Godwit. The new figure of 39,000 is 4,000 smaller than in APEP3, despite the fact that the WeBS graph clearly shows an increase. Interpolation using WeBs figures suggests that the earlier population estimate should have been 31,000, rather than 43,000.

One of the consequences of improved statistical techniques, as used this time around, is the apparent decline in the estimated population of Black-tailed Godwit. The new figure of 39,000 is 4,000 smaller than in APEP3, despite the fact that the WeBS graph clearly shows an increase. Interpolation using WeBs figures suggests that the earlier population estimate should have been 31,000, rather than 43,000. Snipe (Common): The winter estimate remains as 1,100,000 – a figure that was acknowledged in APEP3 as being less reliable than that of most species. At the same time, the GB breeding population was estimated as 76,000 pairs, indicating at least a 4:1 ratio of foreign to British birds, and that does not take account of the number of British birds that migrate south and west. Snipe are ‘amber listed’ but BBS suggests a recent increase of 26% (1995-2018). There is a WaderTales blog about

Snipe (Common): The winter estimate remains as 1,100,000 – a figure that was acknowledged in APEP3 as being less reliable than that of most species. At the same time, the GB breeding population was estimated as 76,000 pairs, indicating at least a 4:1 ratio of foreign to British birds, and that does not take account of the number of British birds that migrate south and west. Snipe are ‘amber listed’ but BBS suggests a recent increase of 26% (1995-2018). There is a WaderTales blog about  The paper in British Birds also includes a table of January population estimates, to provide data that are comparable to mid-winter counts in other countries. These figures are used in waterbird monitoring for the International Waterbird Census for the African Eurasian Flyway. The main table (and figures mentioned above) are average maximum winter counts (in the period September to March). Black-tailed Godwit is one species that illustrates the difference, with a mean of 30,000 in January and a mean peak count of 39,000. Having moulted in Great Britain, some Black-tailed Godwits move south to France and Portugal in late autumn, returning as early as February. January counts are therefore substantially lower than early-winter and late-winter counts. There is more about the migratory strategy employed by Black-tailed Godwits that winter in southern Europe in

The paper in British Birds also includes a table of January population estimates, to provide data that are comparable to mid-winter counts in other countries. These figures are used in waterbird monitoring for the International Waterbird Census for the African Eurasian Flyway. The main table (and figures mentioned above) are average maximum winter counts (in the period September to March). Black-tailed Godwit is one species that illustrates the difference, with a mean of 30,000 in January and a mean peak count of 39,000. Having moulted in Great Britain, some Black-tailed Godwits move south to France and Portugal in late autumn, returning as early as February. January counts are therefore substantially lower than early-winter and late-winter counts. There is more about the migratory strategy employed by Black-tailed Godwits that winter in southern Europe in  The authors have done a tremendous job. They have refined the way that estimates are calculated, they have combined the results from WeBS and NEWS III, and they have delivered population estimates for 25 wader species and many more other species of waterbirds. These population estimates will be used in conservation decision-making until the next set of numbers becomes available. Meanwhile, thousands of birdwatchers will count the birds on their WeBS patches in each winter month, every year. Without them, this paper could not have been written.

The authors have done a tremendous job. They have refined the way that estimates are calculated, they have combined the results from WeBS and NEWS III, and they have delivered population estimates for 25 wader species and many more other species of waterbirds. These population estimates will be used in conservation decision-making until the next set of numbers becomes available. Meanwhile, thousands of birdwatchers will count the birds on their WeBS patches in each winter month, every year. Without them, this paper could not have been written.

When you count the number of Redshank on your local estuary and discover that there are fewer now than there were last year – or five, or twenty years ago – what are the implications? Is this part of a national or international trend or has something changed within the estuary itself?

When you count the number of Redshank on your local estuary and discover that there are fewer now than there were last year – or five, or twenty years ago – what are the implications? Is this part of a national or international trend or has something changed within the estuary itself?  A WeBS count can be a tough assignment for a volunteer birdwatcher. Being allocated to a stretch of an estuarine coastline and asked to visit it, whatever the weather, on a given weekend of every month, in every winter, is not the same as an invitation to go birdwatching in September to look for a Curlew Sandpiper.

A WeBS count can be a tough assignment for a volunteer birdwatcher. Being allocated to a stretch of an estuarine coastline and asked to visit it, whatever the weather, on a given weekend of every month, in every winter, is not the same as an invitation to go birdwatching in September to look for a Curlew Sandpiper. WeBS is the successor of other, similar count schemes which celebrated 70 years of continuous monitoring in 2017/18. It is organised by

WeBS is the successor of other, similar count schemes which celebrated 70 years of continuous monitoring in 2017/18. It is organised by

Habitat availability and site fidelity, along with species longevity, may explain the strong tendency for local population abundance to change much more than site occupancy, in our wintering waders. Given the statutory importance of maintaining waterbird populations in designated protected areas, it is important to continue local and national surveys that can identify changes in local abundance and relate these to large-scale processes.

Habitat availability and site fidelity, along with species longevity, may explain the strong tendency for local population abundance to change much more than site occupancy, in our wintering waders. Given the statutory importance of maintaining waterbird populations in designated protected areas, it is important to continue local and national surveys that can identify changes in local abundance and relate these to large-scale processes.