Your task, should you choose to accept it, is to turn farmland into a haven for breeding waders. The only tools you have at your disposal are tractors and cows and we will give you permission to pump water out of nearby rivers when conditions allow. That’s how it started. These days the diggers look big enough to use on a motorway construction site!

Your task, should you choose to accept it, is to turn farmland into a haven for breeding waders. The only tools you have at your disposal are tractors and cows and we will give you permission to pump water out of nearby rivers when conditions allow. That’s how it started. These days the diggers look big enough to use on a motorway construction site!

If your aim is to maximise the number of pairs of breeding waders on your lowland wet grassland farm or nature reserve, then one of the key issues is to get the water levels right. The first part of this blog focuses on providing an appropriate mix of ditches, pools and grazed grassland for species such as Lapwing, Redshank and Snipe and then keeping everything wet enough (but not too wet) during the important chick-rearing season.

The second part of the blog is not just about maximising the number of breeding waders on a nature reserve. It’s also about working with neighbouring farmers, in order to secure fresh water supplies for the future and to reduce the risk of salt-water inundations, associated with sea level rise. In the long-term, stakeholder engagement has proved far more important than habitat management, as you will read below.

Understanding water levels

When developing lowland wet grasslands for waders, an extra five cm of late-winter rain can make a huge difference, especially if you can capture as much as possible of the rain that falls or can draw water from a swollen river. Mark Smart, the former Senior Site Manager for the RSPB’s Berney Marshes and Breydon Water reserve in East Anglia, understands grazing marshes and how to capture and distribute water, in order to provide the muddy edges where wader chicks find insects. An aerial photograph of Berney Marsh shows how Mark has designed a special landscape to capture winter rain – one that is ideal for Lapwings and other waders.

Mark has taken the lessons he has learnt on RSPB nature reserves and shared them widely, a contribution to conservation that earned him one of the 2018 Marsh Awards for Wetland Conservation from the Wildfowl & Wetland Trust.

From wheat and barley to ducks and waders

The marshes of the Norfolk Broads have been drying out for 2000 years. By the 1970s, and after over 400 years of farming, the Halvergate Marsh complex was on the point of being fully drained and by 1985 much of the wet grassland in which waders formerly bred had already been lost and turned into arable fields. At this point, the RSPB made its first purchase of land, as they tried to retain at least some of the threatened habitat which is so important to winter wildfowl and summer waders. At the same time, campaigning by local and national conservationists secured legal protection for the unique Broadland scenery and the species that rely upon the habitats it contains, thereby halting the advance of the combine harvesters.

The marshes of the Norfolk Broads have been drying out for 2000 years. By the 1970s, and after over 400 years of farming, the Halvergate Marsh complex was on the point of being fully drained and by 1985 much of the wet grassland in which waders formerly bred had already been lost and turned into arable fields. At this point, the RSPB made its first purchase of land, as they tried to retain at least some of the threatened habitat which is so important to winter wildfowl and summer waders. At the same time, campaigning by local and national conservationists secured legal protection for the unique Broadland scenery and the species that rely upon the habitats it contains, thereby halting the advance of the combine harvesters.

The importance of Halvergate Marshes for wildlife has long been known, and in 1987 it became the site of the UKs first Environmentally Sensitive Area – the prototype for subsequent agri-environment schemes. Lowland wet grasslands are traditionally drained using ‘footdrains’ – narrow, shallow channels that connect low-lying parts of the fields with surrounding ditches, in order to drain them.

The muddy edges of a footdrain

These same footdrains can be used to hold and manage surface water levels within fields, by blocking the ditch connections with sluices. In the 1990s, Mark pioneered the design and deployment of footdrains on lowland wet grasslands, and the kit needed for their construction. Through his skills, enthusiasm and collaborations with grassland managers throughout lowland England, footdrains and the water that they can contain are now a common sight. Many generations of wader families have enjoyed the invertebrate food that footdrains support.

The breeding season for waders is very short – with the first Lapwing claiming territories in March and most chicks fledged by the end of July. Outside these months, these wet grasslands provide excellent grazing for geese and ducks in the winter and cattle in the summer. The task of nature reserve managers is to work with graziers to try to ensure that cattle deliver appropriate sward heights for winter wildfowl and summer waders.

Not just water

By creating a hot-spot for nesting birds, within an intensively-farmed landscape, land-managers also produce a food-rich area for predators, attracted in by concentrations of eggs, chicks and sitting adults. Restricting the activities of species such as foxes and crows is an important part of the role of an RSPB warden, carried out through site management and active control measures. By focusing these activities in the winter period, the RSPB’s Halvergate Marshes team are able to stop corvids and foxes from setting up territories within the area that is managed for breeding waders. Electric fencing can help to prevent foxes moving onto the site in spring, while changing the way that core wader areas are managed helps to reduce fox/nest interactions by, for instance:

By creating a hot-spot for nesting birds, within an intensively-farmed landscape, land-managers also produce a food-rich area for predators, attracted in by concentrations of eggs, chicks and sitting adults. Restricting the activities of species such as foxes and crows is an important part of the role of an RSPB warden, carried out through site management and active control measures. By focusing these activities in the winter period, the RSPB’s Halvergate Marshes team are able to stop corvids and foxes from setting up territories within the area that is managed for breeding waders. Electric fencing can help to prevent foxes moving onto the site in spring, while changing the way that core wader areas are managed helps to reduce fox/nest interactions by, for instance:

- Adding shallow ditches in the right places can break up the site into compartments and reduce the likelihood that nests will be predated.

- Leaving areas with long grass, that is good for small mammals and the mustelids and foxes that prey upon them, can change the focus of hunting activities.

- Erecting temporary fencing, during at least the early part of the nesting season, can both provide protection and potentially increase the synchronicity of nesting attempts and hence the ability of birds effectively to mob predators.

There is more about these measures in these blogs, with links to papers from the RSPB and University of East Anglia team of conservation researchers:

There is more about these measures in these blogs, with links to papers from the RSPB and University of East Anglia team of conservation researchers:

- A helping hand for Lapwings investigates ways of keeping predators and wader chicks apart.

- Can habitat management rescue Lapwing populations? Might the right mix of pools and verges with long grass provide a big enough uplift in nest success rates?

- Tool-kit for wader conservation provides an overview of the tools that are available to conservationists and site-managers working on wet grasslands.

There is annual management of the Berney site too, with foot-drains to be re-cut, spoil to be spread in ways that can provide a mix of water-levels and more muddy edges, and rotovation of some areas to increase the diversity of habitats. These techniques might seem rather different to the ones that are used by farmers but many of the other operations at Berney are the same as would be seen outside nature reserves, with fences to mend, stock to manage and creeping thistle and rush to ‘weed-wipe’.

Rotovation, carried out in dry conditions, adds heterogeneity and creates bare, muddy areas

Measuring success

The development of Berney Marshes has been hugely successful. Back in 1987, there were only 13 pairs of wader breeding on the site – nine pairs of Redshank and four of Lapwing. The total for 2019 looks like being about 270 pairs – over twenty times as many.

Redshank: The graph alongside illustrates how Redshank numbers have changed across the decades. At the same time as Breeding Bird Survey (BTO, JNCC & RSPB) for England results revealed huge declines, with a loss of nearly half in the period 1995-2017, Redshank pairs on Berney Marshes have been increasing. Even on this site, there is a suggestion that the peak number of pairs may be in the past. Given the pressures on breeding Redshank on saltmarsh habitats (blog: Redshank – the ‘warden of the marshes’), providing breeding habitat in coastal marshes, inside sea-walls, may be particularly important. Hopefully, the latest earthworks (see later) will create more space for Redshank.

Redshank: The graph alongside illustrates how Redshank numbers have changed across the decades. At the same time as Breeding Bird Survey (BTO, JNCC & RSPB) for England results revealed huge declines, with a loss of nearly half in the period 1995-2017, Redshank pairs on Berney Marshes have been increasing. Even on this site, there is a suggestion that the peak number of pairs may be in the past. Given the pressures on breeding Redshank on saltmarsh habitats (blog: Redshank – the ‘warden of the marshes’), providing breeding habitat in coastal marshes, inside sea-walls, may be particularly important. Hopefully, the latest earthworks (see later) will create more space for Redshank.

Left image below shows Redshank nest in a clump of grass. The right image shows a Lapwing nest in a newly-rotovated patch.

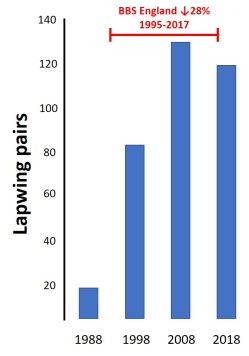

Lapwing: Between 1988 and 1998, the number of pairs of Lapwing rose from 14 to 79, reaching a peak of 157 in 2010. Numbers vary, according to spring weather and water levels, with between 83 and 130 pairs in the years 2011 to 2019. The national decline in England was 28% between 1995 and 2017 (Breeding Bird Survey) – not quite as drastic as for Redshank but still worrying. Intensive studies at Berney have shown that productivity is only high enough to boost numbers in some years. The latest project by UEA and RSPB conservation scientists involves trialling temporary electric fences to provide protection for first clutches and broods. Hopefully Berney can become a net exporter of Lapwings in most years.

Lapwing: Between 1988 and 1998, the number of pairs of Lapwing rose from 14 to 79, reaching a peak of 157 in 2010. Numbers vary, according to spring weather and water levels, with between 83 and 130 pairs in the years 2011 to 2019. The national decline in England was 28% between 1995 and 2017 (Breeding Bird Survey) – not quite as drastic as for Redshank but still worrying. Intensive studies at Berney have shown that productivity is only high enough to boost numbers in some years. The latest project by UEA and RSPB conservation scientists involves trialling temporary electric fences to provide protection for first clutches and broods. Hopefully Berney can become a net exporter of Lapwings in most years.

Oystercatcher: There were no Oystercatchers breeding at Berney back in 1997. The peak number of pairs was 18 in 2009, with an average of ten pairs in subsequent years. Nationally, numbers in England have increased but with major declines in Scotland, which is the species’ heartland within the UK. This is discussed in an earlier WaderTales blog.

Avocet: The RSPB’s logo species has been hugely successful, nationally, with the help of protection and habitat creation. The first pair of Avocets bred at Berney in 1992 and pairs have bred in most years since then, with over thirty pairs in nine years but no pairs in 2013 or 2014. The 2019 count is 35 pairs and there is potential for further growth in numbers across the site, with the creation of more island homes (see below).

Combined harvesters have been replaced by nesting Avocets

Snipe: Despite all of the excellent habitat creation work, there have never been more than 8 pairs of Snipe recorded on Berney and only between 0 and 3 pairs in each of the last ten years. The underlying soils at Berney are clay-based, which may not suit this species.

Sharing the knowledge

Redshank chick: science is an important feature of the work at Berney

Although it’s great that the RSPB has been able to buy and develop land for breeding waders in the Yare Valley, the impact of their work has been far larger, thanks to management agreements with other landowners. Mark Smart and the RSPB have set up Broads Land Management Services, to deliver wet grasslands that attract the top tier of conservation payments for farmers working in the Broads. Much of the recent work has been part of the Water Mills and Marshes Project, funded by HLF and led by the Broads Authority. Using specialist ditch-cutting and spoil-spreading equipment, the team has been able to create wet features within top-quality grazing fields. This is not just a local initiative; the kit and the advice have had impacts on farms and nature reserves across the country.

For his work for wetland conservation, Mark Smart received a Marsh Award for Wetland Conservation from the Wildfowl & Wetland Trust in 2018. “Mark Smart received his award for his 17 years managing RSPB Berney Marshes in the Norfolk Broads. Over this period, he brought together landowners, conservationists, local authorities and scientists to improve the marshes for wildlife. Today more than 300 pairs of wading birds nest there each spring, and more than 100,000 waterbirds return to it each winter.”

Illustrations above shows work that has been completed at Somerleyton in Suffolk and a newly-fledged Lapwing.

Working with Jen Smart, who was a Principal Conservation Scientist at the RSPB’s centre for Conservation, Mark has added a Dutch dimension to the RSPB’s advice work by co-authoring “Meadowbirds on the horizon of southwest Friesland”. This report has just been published by the International Wader Study Group.

Working with Jen Smart, who was a Principal Conservation Scientist at the RSPB’s centre for Conservation, Mark has added a Dutch dimension to the RSPB’s advice work by co-authoring “Meadowbirds on the horizon of southwest Friesland”. This report has just been published by the International Wader Study Group.

Climate – ‘the new normal’

Fresh water is an increasingly important commodity in East Anglia – for farmers and for nature reserve wardens, looking to maximise agricultural and wader chick production. More extreme weather patterns are already producing periods of drought and intense periods of rain, while a rising sea-level is increasing the salinity of rivers and limiting extraction opportunities. Broadland farmers are looking for a reliable water supply, the Environment Agency is looking for ways to reinforce sea defences and for places to store fresh water, in order to avoid flooding, and the RSPB wants to hold more water in the late winter that can be used to keep areas wet in the early summer. With some lateral thinking, many of the needs of these key stakeholders can be met in partnership projects, as shown below

The Environment Agency’s need for material to raise sea defences provided Mark Smart with an opportunity to provide more pools and scrapes for breeding waders. It was a win-win solution; free habitat creation work for the RSPB and minimal movement of the clay and top-soil that the Environment Agency needed. In the images below, you can see this work in progress and the islands that are now being used by nesting Avocets.

The most recent project is an ambitious water storage and flood reduction scheme for the whole of Halvergate Marsh. This will keep salt water out of these important grazing marshes and store fresh water for summer use. The £2 million Halvergate Marshes Water Level Management Improvement Scheme is a joint initiative, funded by DEFRA and delivered by the Water Management Alliance. The project involves a large number of stakeholders, including the Broads Internal Drainage Board, RSPB and neighbouring farming estates.

The Water Level Management Improvement Scheme is a huge undertaking, with 8 km of new ditches, 240 piped culverts and 12 big sluices, that will create storage for 60,000 cubic metres of fresh water and systems to distribute this water over the course of a dry East Anglian summer. One of the most impressive features of the project, illustrating the imagination of the design team, is the Higher Level Carrier, a ‘flyover’ ditch system that passes over the top of existing wet grazing land to get water to some of the driest part of Halvergate Marshes (left picture below). This high-level water transportation route was constructed using locally-sourced clay, thereby creating shallow pools around which yet more waders are already nesting.

When designing this project, the opportunity was taken to develop opportunities for birdwatchers to see the birds that will be drawn into the wettest areas, by making sure that the ‘best bits’ are close to public access points on the Weavers’ Way, the 61 mile (100 km) long-distance path running from Cromer to Great Yarmouth.

Aspirations

Mark Smart has not finished yet! Plans are afoot to develop the RSPB’s land that is closest to Great Yarmouth, recently purchased using a WREN grant. If agreed, this can provide an alternative, safe high-tide refuge area for tens of thousands of waders and wildfowl that roost on the mud and saltmarsh at the mouth of the Yare. Their current high-tide refuge is threatened by sea-level rise and developments proposed for the outskirts of Great Yarmouth.

This proposed roosting area will be part of an extension to the Halvergate Marshes Water Level Management Improvement Scheme, which will add another 10,000 cubic metres of water storage. Alongside flood alleviation and fresh-water conservation, this scheme will create fifty hectares of additional shallow wader and waterfowl scrapes adjacent to Breydon Water.

The new scrapes should not only attract wintering and breeding birds but also many passage waders, such as the Wood Sandpiper pictured to the right. The whole scheme has the potential to be another win-win-win-win, for the owners of low-lying properties, for Broadland farmers, for internationally important bird populations and for local and visiting birdwatchers.

The new scrapes should not only attract wintering and breeding birds but also many passage waders, such as the Wood Sandpiper pictured to the right. The whole scheme has the potential to be another win-win-win-win, for the owners of low-lying properties, for Broadland farmers, for internationally important bird populations and for local and visiting birdwatchers.

Read more

Information about the RSPB’s Berney Marshes & Breydon Water reserve can be found on the RSPB’s website. Click here.

There is information about the Water, Mills and Marshes project here.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton, to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on previously published papers, with the aim of making wader science available to a broader audience.