You may hear the distinctive seven-note call of a Whimbrel overhead in late April or May but where is it going and where has it been?

Many pairs of Whimbrel nest in the flood-plains of Iceland’s rivers (Tómas Gunnarsson)

In a 2016 paper in Wader Study, Tómas Gunnarsson and Guðmundur Guðmundsson analysed the ringing recoveries of Icelandic Whimbrel and demonstrated that many probably make non-stop flights from Iceland to western Africa. The study also helped to explain the timing and origins of flocks of Whimbrel in different parts of the British Isles in spring and late summer.

Migration and non-breeding distribution of Icelandic Whimbrels Numenius phaeopus islandicus as revealed by ringing recoveries: Tómas Grétar Gunnarsson and Guðmundur A. Guðmundsson (Wader Study). The paper is available here.

Since the publication of this paper, further details has been added using geolocators, small tags that collect information on the movements of birds over a twelve-month period, and now using satellite tracking. There’s more about this work at the end of this blog.

Whimbrels in Iceland

It is estimated that 250,000 pairs of Whimbrel breed in in Iceland, representing 25% of the combined global population for all seven subspecies of Whimbrel and making Iceland a very important country for the species. The Icelandic breeding population is believed to be relatively stable but others, such as those in North America, are in decline.

There are two blogs about how volcanic dust affects Whimbrel. In the long-term volcanic ash provides important fertilizers but short term effects can be seen in breeding success.

The Whimbrel is one of the commonest of Iceland’s breeding wader species, with most nests estimated to be at elevations lower than 200m and particularly along river flood-plains.

Iceland is a country in a state of constant flux, both because of geothermal activity and the subsequent physical processes associated with wind and water flow, and as a result of human interventions. Volcanic ash has been shown to affect the breeding success of Whimbrels in the short term and their distribution in the longer term. Land use is also changing rapidly, particularly as a result of afforestation and the ways that land is farmed, and work is ongoing to understand how these processes might impact upon breeding waders, including Whimbrels.

Movements of Icelandic Whimbrel

Nesting Whimbrel hunkers down in heathland vegetation – a very different habitat to the mud and mangroves of West Africa (Tómas Gunnarsson)

Over 6000 Whimbrels have been ringed in Iceland since 1921, with 95% of these caught as chicks. 35 Icelandic-ringed Whimbrels have been recovered abroad and 4 foreign-ringed Whimbrels have been found in Iceland. In their paper, Tómas and Guðmundur show that most of the winter records of Icelandic birds are in west Africa, between Mauritania in the north and Benin and Togo in the south, but that there are two January records in Spain, suggesting that some individuals don’t travel further south than Europe. Spain and Portugal cannot be particularly important wintering areas for the species, however, as Whimbrel counts across Spain and Portugal don’t exceed 1000 birds, which represents a tiny part of the Icelandic population, even if they are all assumed to originate from there.

Reproduced from Gunnarsson & Gudmundsson 2016 with permission from Wader Study

Spring and autumn Whimbrel records that link Iceland with Britain and Ireland show strikingly different distributions for the two seasons. There are eight recoveries in the British Isles on spring passage; 1 in Ireland and 7 in western counties of the UK. There is only one autumn passage record (in the Outer Hebrides), despite the fact that autumn shooting of Curlew, which did not stop until 1981, might have been expected to have produced recoveries of similar Whimbrel. This strongly suggests that, while some whimbrel stop off on northwards migration, the southerly journey is straight to Africa. We know that this is possible, because a satellite-tagged Whimbrel was tracked making a direct flight from Iceland to Guinea-Bissau in late summer 2007.

Counts and recoveries of British birds

Some of the big WeBS counts for Whimbrel are made in the late summer, with over 1500 birds reported on the Wash (August), nearly 300 along the North Norfolk coast (August) and nearly 200 in July in each of Chichester Harbour (Hampshire) and Morecambe Bay. Largest counts in spring are mainly in the west and all in April, with 331 on the Severn, 339 on the Ribble and 654 in the Fylde area but one east coast site (Breydon Water in Norfolk) has had a spring count of 137. Although April & May flocks might seem large, they should be viewed in context – at least 500,000 Whimbrel travel back to Iceland each year.

The only British-ringed Whimbrels to have been found in Iceland have been two satellite-tagged birds, one of which is mentioned above, but metal-ringed birds have returned to breeding grounds in Finland, Russia and Sweden. Given that this new paper suggests no links between eastern Britain and Iceland in the autumn, it is likely that the large number of birds that spend the moult period on east coast estuaries such as the Wash are mainly of continental origin. The same is probably true for late-summer gatherings, such as the ones in Chichester Harbourand Morecambe Bay.

Tómas Gunnarsson

In order to understand more about spring flocks of Whimbrel in the UK, ringing and satellite tagging has been taking place in the Lower Derwent Valley (East Yorkshire). Birds tagged here have flown to both Iceland and Sweden which indicates that Icelandic and continental birds gather together in April and May flocks. Despite this mix of subspecies in Yorkshire, the lack of ringing recoveries of Icelandic birds in the east of the UK suggests that continental birds make up the majority of spring flocks in the east.

To summarise: if you hear a Whimbrel calling overhead in the autumn it is probably of continental origin, especially in the east. On spring passage, a seven-note call in the west may well have an Icelandic twang but in the east it could sound that little bit more Scandinavian. If only we could tell them apart.

To learn more about the migration of over 40 wader species to, from and through Britain & Ireland, check out this WaderTales blog.

Update: Tracking helps to provide more insights

Tómas Gunnarsson

This analysis of metal-ringed birds set the context for new studies to understand the migration strategies of individual Icelandic birds, using geolocators and satellite tags.

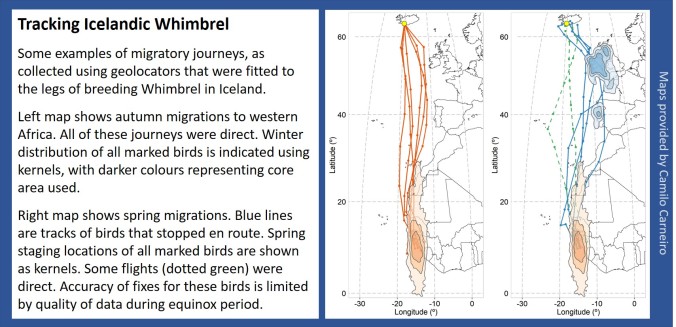

The first paper using these data appeared in Nature’s Scientific Reports. In it, José Alves and his colleagues show that four birds completed the autumn migration in one flight. On return in spring, two of these birds stopped off in Ireland and two flew straight to Iceland.

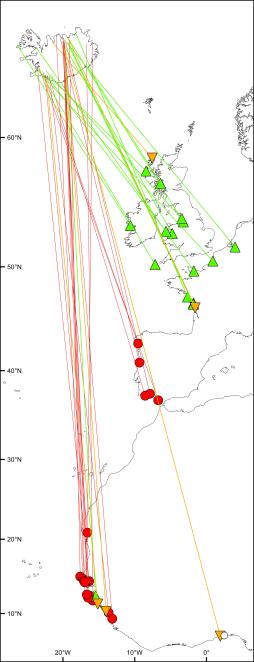

Camilo Carneiro developed the work further, working with supervisors Tómas Gunnarsson and José Alves. By increasing the sample size of birds carrying geolocators from Iceland and back again, he was able to show that all of the adults in his sample were able to migrate directly from Iceland to West Africa at the end of the breeding season. Only 20% of journeys north in the spring were completed without refuelling. Most of these stops were in Ireland and western Britain, as predicted from the results of the ringing analyses summarised above. See Iceland to Africa non-stop.

By tracking birds in more than one year, Camilo has gone on to show that the fixed point in an Icelandic Whimbrel’s annual cycle is spring departure from Africa. See Whimbrel: time to leave.

By tracking birds in more than one year, Camilo has gone on to show that the fixed point in an Icelandic Whimbrel’s annual cycle is spring departure from Africa. See Whimbrel: time to leave.

With further research it should soon be possible to understand how these epic sea crossings from Iceland to Africa are affected by prevailing winds and varying weather patterns, whether individuals use the same strategies in different years and if a juvenile can make it all the way to Africa on its maiden flight.

With further research it should soon be possible to understand how these epic sea crossings from Iceland to Africa are affected by prevailing winds and varying weather patterns, whether individuals use the same strategies in different years and if a juvenile can make it all the way to Africa on its maiden flight.

Meanwhile, you can help with the studies of migration by looking out for and reporting colour-ringed Whimbrel. Most of the ones seen in Britain & Ireland will have been marked by researchers in Iceland and they will be delighted to hear news of their birds at icelandwader@gmail.com.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton, to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on previously published papers, with the aim of making wader science available to a broader audience.