If a Curlew can live for over 32 years and there are flocks of 1000 in Norfolk, how can they be described as near-threatened?

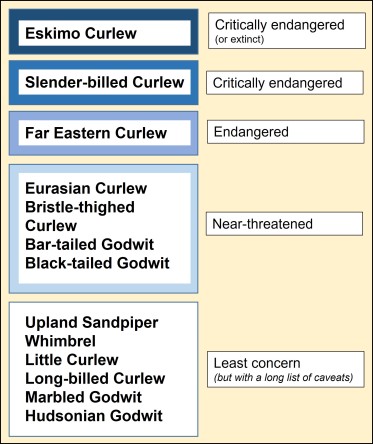

Thirty years ago there were eight members of the world-wide curlew family but now we may well be down to six. The planet has lost one species, the Eskimo Curlew, with no verified sightings since the 1980s, and probably the Slender-billed Curlew as well. Of the others, Far Eastern Curlew and Bristle-thighed Curlew are deemed to be endangered and vulnerable**, respectively, and our own Curlews are classed as near-threatened, which is the next level of concern. This may seem strange, especially when flocks of 1000 can be seen on the Norfolk coast. However, evidence suggests that we should take heed of what is happening to other members of the curlew family, as we consider the future of this evocative species with its wonderful bubbling curl-ew calls.

Thirty years ago there were eight members of the world-wide curlew family but now we may well be down to six. The planet has lost one species, the Eskimo Curlew, with no verified sightings since the 1980s, and probably the Slender-billed Curlew as well. Of the others, Far Eastern Curlew and Bristle-thighed Curlew are deemed to be endangered and vulnerable**, respectively, and our own Curlews are classed as near-threatened, which is the next level of concern. This may seem strange, especially when flocks of 1000 can be seen on the Norfolk coast. However, evidence suggests that we should take heed of what is happening to other members of the curlew family, as we consider the future of this evocative species with its wonderful bubbling curl-ew calls.

** Bristle-thighed Curlew has now been changed to ‘near-threatened’. Graphic alongside has been changed.

Our Curlew – more properly called the Eurasian Curlew – was until relatively recently a locally popular game species in Britain, especially in September and October, when birds are reputed to be particularly flavoursome. A male Curlew is equivalent in weight to a Wigeon (or two Teal) and the bigger female may well be as heavy as a Mallard, so it is not surprising that they were worth targeting. They came off the British quarry list in 1981.

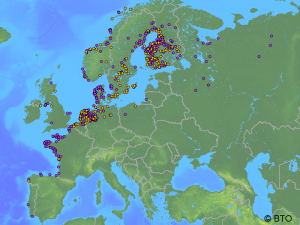

Purple dots indicate where British/Irish ringed Curlews have been recovered and orange dots show ringing sites of birds found here and wearing foreign rings. Maps of movements can be found at http://www.bto.org/volunteer-surveys/ringing/publications/online-ringing-reports

The Curlews that we see on the Norfolk coast in autumn and winter are drawn from a wide breeding area; some are of British origin but many are from Scandinavia, Finland and Russia. The Wash Wader Ringing Group recently received a report of a bird that was ringed in Norfolk in September 2000 and recovered in Izhma in Russia in May 2014. At 3300 km (2000 miles) this is nearly as far away as the furthest east dot on the map of Curlew recoveries, shown here and published on the website of the British Trust for Ornithology. The bird was an adult when ringed so must have been at least 15 years old when shot. This seems like a good age for a Curlew but is less than half of the British longevity record, set by a chick ringed in Lancashire in 1978 and found dead on the Wirral in 2011.

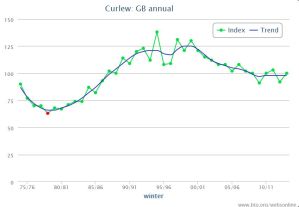

Curlew numbers on the Wash, which sits between the counties of Norfolk and Lincolnshire, increased dramatically when shooting ceased in 1981, although milder winters could have also have been influential. In the five years immediately before the ban, the average maximum, winter Wetland Bird Survey count on the Wash was 3281, rising to 9642 in the period 2006/07 to 2010/11. There were similar increases on the North Norfolk coast and a bit further south at Breydon Water. The broader, national picture is one of increase between 1981 and 2001, although generally at a lower level to that seen in Norfolk, followed by a steady, shallow decline. If numbers are higher than they once were does this mean that we should be less concerned about Curlews – and what is the justification of the species’ near-threatened designation?

Curlews fly vast distances to spend the winter on the estuaries of Britain & Ireland (© Graham Catley)

Conserving migratory species is difficult because individuals rely on different resources in different countries at different stages of the year. For Curlews, there is evidence that breeding season problems are at the heart of large decreases in numbers in Russia, through the Baltic and into The Netherlands – the countries from which much of the wintering population on the east coast is drawn. According to the European Commission’s species management plan, drivers of decline include wide-scale intensification of grassland management for milk production, land-abandonment and increased predation in some areas. Autumn, winter and spring hunting is thought to have had a lesser but contributory effect to the long-term losses, with hunters across the European Community shooting between 3% and 4% of the population each year. In the last twenty years, within the EC, hunting of Curlew has been confined to Ireland, Northern Ireland and France. Much of this shooting pressure was and in France, where coastal hunting of Curlew was reinstated after a five year moratorium but has since been suspended again. Read blog about this here.

Focusing on Britain and Ireland, we have seen major losses in our breeding populations. In Ireland, the Curlew population is estimated to have dropped from 5000 to 200 pairs in the twenty years between 1991 and 2011 (with further declines since – see Ireland’s Curlew Crisis blog below). There has been an 80% decline in Wales and other losses elsewhere. There’s more about these distributional changes in a 2012 article written for the BTO website.

Focusing on Britain and Ireland, we have seen major losses in our breeding populations. In Ireland, the Curlew population is estimated to have dropped from 5000 to 200 pairs in the twenty years between 1991 and 2011 (with further declines since – see Ireland’s Curlew Crisis blog below). There has been an 80% decline in Wales and other losses elsewhere. There’s more about these distributional changes in a 2012 article written for the BTO website.

Curlew productivity in several areas appears to be very low and it is possible that the adults we are seeing are part of an ageing population. As has been shown in seabirds, counts of adults can give a false sense of security, as it is easy not to notice that there is little recruitment of new, breeding adults into the population, with obvious long-term consequences.

Graph shows the changing Curlew population in Great Britain (Wetland Bird Survey)

The decline in the number of breeding Curlew in Great Britain is clearly reflected in monthly, winter counts undertaken by volunteers on west coast estuaries. On the Dee, for instance, the average peak-winter count dropped from 6109 in the early 1970s to 4348 in the five years after the shooting ban, rose to 5081 in the late 1990s but then slipped back to 3802.

In Ireland and Northern Ireland, a total ban on shooting Curlew was announced in 2012, brought in once it was clear that the estimated November harvest of between 6% and 8% was unsustainable and set against a background of the collapse of the local breeding populations. The same local reasoning lies behind continuing protection in Wales, western England and in much of Scotland, especially at a time when financial support to land-managers is being used to try to bolster British breeding numbers. In eastern England, Curlew conservation has a more international flavour, as we provide a safe haven for birds from as far away as Russia.

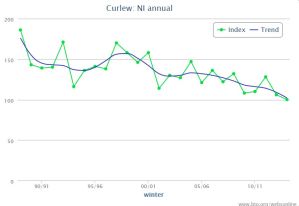

With relatively few continental birds in Northern Ireland, the Wetland Bird Survey trends probably reflect local declines

Britain & Ireland, between them, provide winter homes for half of the Europe-wide population of Curlews (about 210,000 out of 420,000), with the Netherlands holding 140,000 birds. There are also significant flocks in Germany and about 20,000 in France. These may seem like reasonable numbers but, given that fewer chicks are being raised, the number of adults is declining, two close relatives have been driven to extinction and other curlew species are in trouble, the label of near-threatened seems highly appropriate.

We should be proud of our wintering Curlews in Great Britain, where numbers have stabilised, albeit at a level that is 20% lower than at the turn of the century, but there is no room for complacency in Northern Ireland, where the decline continues.

Update: Curlew was added to the red list of the UK’s Birds of Conservation Concern on 3 December 2015

Other WaderTales blogs about Curlew

- Why are we losing our large waders? takes a look at a review of the common threats faced by the 13 Numeniini species (godwits, curlews and Upland Sandpiper).

- Curlews can’t wait for a treatment plan focuses on the primary drivers of the species’ breeding decline in Great Britain.

- Sheep numbers and Welsh Curlew looks at habitat associations within a large site in the Welsh uplands; getting the grazing regime right seems to be very important.

- Curlew Moon has at its heart a review of Mary Colwell’s book of the same name but also summarises some of the issues being faced by Curlew in Ireland and the UK.

- Ireland’s Curlew Crisis focuses on the nationwide breeding survey between 2015 and 2017, which revealed a 96% decline in the number of pairs in just 30 years.

- Curlews and foxes in East Anglia suggest that ‘curlew plots’ may be helpful in the fight to conserve the species.

- More Curlew chicks needed has at its core a paper about survival rates of breeding and wintering Curlew. Even in a period of historically low annual adult mortality, breeding numbers have continued to fall.

- The flock now departing reveals fascinating details about Curlew migration with descriptions of four occasions when two tagged birds ended up in the same migratory flock.

- Curlew: after the hunting stopped describes changes to survival rates of Curlew wintering in England & Wales in the period since the species was taken off the shooting list.

- A Norfolk Curlew’s summer follows ‘Bowie’ from April to July. It includes a stoat attack, the brief life of ‘miracle chick’ and autumn migration to Montijo in Portugal, a site threatened by a new airport.

- Will head-starting work for Curlew? There are very few breeding Curlew in southern England. Can head-starting boost numbers while conservationists try to tackle habitat and predator issues?

- Curlew nest survival examines if there are conditions in Breckland (East England) that can deliver the levels of success that will deliver sustainability.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton, to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on previously published papers, with the aim of making wader science available to a broader audience.

Pingback: NEWS and Oystercatchers for Christmas | wadertales

Pingback: What’s in WaderTales – so far? | wadertales

Pingback: Then let the bird find you. | Curlews' Feathers

Pingback: Tracking waders on the Severn | wadertales

Pingback: All downhill for upland waders? | wadertales

Pingback: Are there costs to wearing a geolocator? | wadertales

Pingback: Oystercatchers: from shingle beach to roof-top | wadertales

Pingback: Establishing breeding requirements of Whimbrel | wadertales

Pingback: WaderTales: a taste of Scotland | wadertales

Pingback: Wales: a special place for waders | wadertales

Pingback: Why are we losing our large waders? | wadertales

Pingback: Flyway from Ireland to Iceland | wadertales

Pingback: Which wader, when and why? | wadertales

Orkney Silage is cut at the end of June, fledgling Curlew are still in the fields .How long before the call of Curlew in Orkney is as rare as the Corncrake. Global warming ? or is it the way the grass is managed .

LikeLike

Pingback: Curlews can’t wait for a treatment plan | wadertales

Pingback: Wetland Bird Survey: working for waders | wadertales

Pingback: Sheep numbers and Welsh Curlew | wadertales

Pingback: Scottish wader woes | wadertales

Pingback: Curlew Moon | wadertales

Pingback: Black-tailed Godwit and Curlew in France | wadertales

Pingback: A Walk for World Curlew Day – The Wax Picture Sandbox

Pingback: Ireland’s Curlew Crisis | wadertales

Pingback: Do population estimates matter? | wadertales

Pingback: Sixty years of Wash waders | wadertales

Pingback: The waders of Northern Ireland | wadertales

Pingback: Nine red-listed UK waders | wadertales

Pingback: Curlews and foxes in East Anglia | wadertales

Pingback: Coming soon | wadertales

Pingback: The First Five Years | wadertales

Pingback: Waders on the coast | wadertales

Pingback: More Curlew chicks needed | wadertales

Pingback: Eleven waders on UK Red List | wadertales

Pingback: Will head-starting work for Curlew? | wadertales

Pingback: UK waders: “Into the Red” | wadertales

Pingback: Inland feeding by coastal godwits | wadertales