It is estimated that 120,000 Eurasian Curlew spend the winter in Great Britain, with a further 28,300 on the island of Ireland (Note). Counts made by Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) volunteers in Great Britain show that the winter population increased following the end of Curlew hunting in 1982 but has since decreased. A paper in Bird Study by Ian Woodward et al investigates how much the temporary recovery was ‘cause and effect’ and asks what other processes may be important, locally and regionally.

Note: Figures from reports in British Birds and Irish Birds, as summarised in the WaderTales blogs, Do populations estimates matter? and Ireland’s wintering waders.

Curlew problems

The 13 species of the Numeniini tribe (curlews, godwits & Upland Sandpiper) are in trouble, with two species probably extinct (as discussed in Why are we losing our large waders?). Eurasian Curlew is red-listed in the UK and described as ‘near-threatened’ internationally.

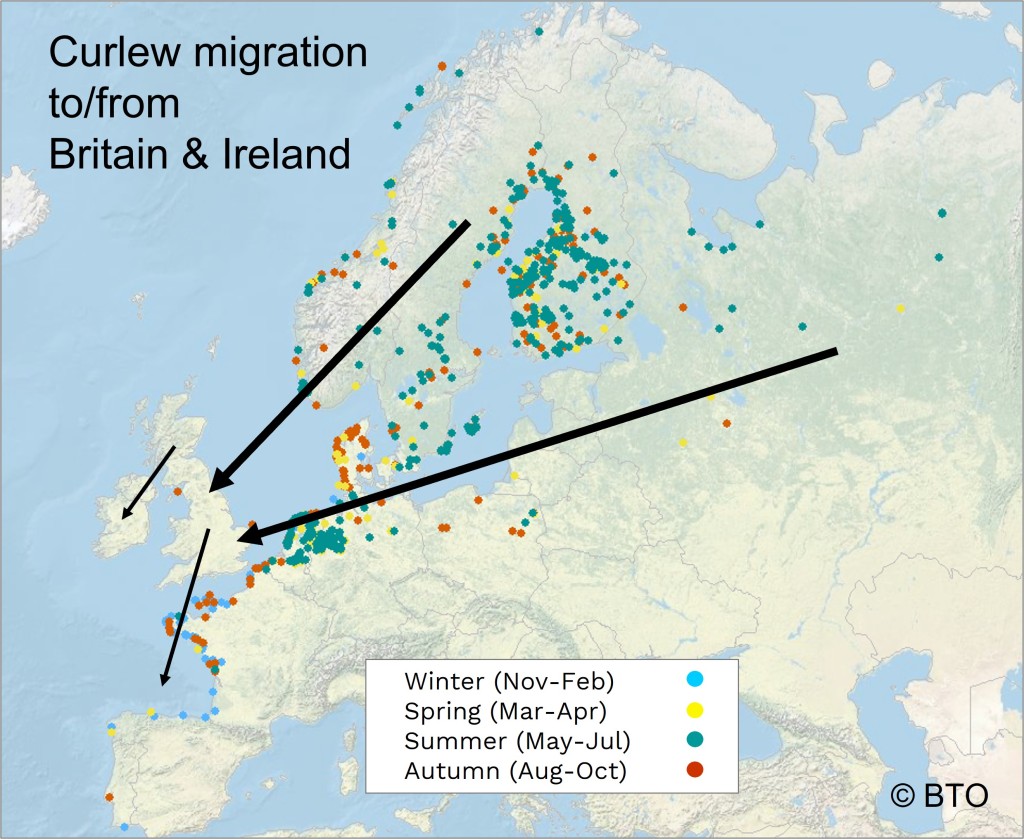

The wintering Curlew population of Britain and Ireland is made up of birds that move around within these islands and others that breed as far east as Russia. The breeding population of Curlews in the UK declined by 48% over the period 1995-2018, according to Breeding Bird Survey data, but numbers were probably higher still in the preceding period. Trends in other countries are mixed; across Fennoscandia there have been increases in Finland but declines in Sweden, for instance, as discussed in Fennoscandian wader factory.

In the autumn, some UK-breeding Curlew migrate south and west but there are larger arrivals, especially from Finland. Winter numbers on estuaries and wetlands are monitored by WeBS counters, with supplementary information for coastal birds collected periodically (see Waders on the coast). Curlews are site-faithful to wintering sites, so changes in abundance on an estuary will largely depend upon the annual survival of adults that use the site and the recruitment of juveniles.

To survive the winter, a Curlew needs access to sufficient food and to be able to build up fat stores so that it can cope with periods of freezing conditions, when energy loss is high and access to food is limited. In Great Britain, up until 1982 there were additional losses due to hunting. The study led by Ian Woodward aims to establish the local and broadscale factors that might have influenced annual changes in the numbers of Curlew using wintering sites.

Curlew hunting

The estuaries of Britain and Ireland are of huge importance to Europe’s Eurasian Curlew, being significantly warmer than sites in continental Europe on similar latitudes. It is estimated that at least 20% of the European population winters in the British Isles. An adult Curlew is almost as heavy as a Mallard, so it is unsurprising that the species was pursued by hunters, particularly wildfowlers, who encountered them on the foreshore and on wetland sites. When the list of species that could be legally hunted was revised, as part of work to develop the Wildlife & Countryside Act of 1981, Curlew numbers were falling. Shooting of Curlew in Great Britain stopped in 1982 but continued until 2011 in Northern Ireland and 2012 in Ireland.

The national graph from the Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) can be divided into four sections. There was a rapid decline in wintering numbers during the 1970s, with the UK population reaching a low point in about 1980. Numbers increased rapidly for the next 15 years and then there was a period of relative stability between 1995 and 2000. Since then, the trend has been downwards.

Although not considered in this study (because annual count data are not collected) it is interesting to note that, in the period between 1997/98 and 2015/16, counts of Curlew on open coasts declined more rapidly than on estuarine sites covered by WeBS (40%, compared to 26%). See Waders on the coast.

Looking closely at the WeBS graph, signs of recovery of the UK wintering Curlew population were evident before 1982, when hunting ceased in Great Britain. With numbers falling in the late 1970s, it is possible that hunters chose not to target Curlew, either because they were worried about sustainability or because there were fewer to hunt. Sadly, there is no systematic recording of bag numbers that might help to explain why the upturn in the Curlew graph started before the species received full protection.

Detective work

Ian Woodward and his colleagues started by considering a range of potential drivers of change, other than reduced hunting pressure. Have numbers responded positively to warmer winter temperatures, and might this effect be more obvious in colder regions of the UK? Are there different trends in some estuaries, potentially linked to water quality or the ability to switch to feeding in fields?

The main data available to the BTO team were monthly WeBS counts from north-west England, the Midlands, south-west England, southern England, Anglian region, north-east England and Wales. There was particular focus on 46 estuaries with largely complete datasets and for which comparable environmental data were also available: estuary structure, the presence of coastal grassland feeding areas, potential disturbance and water quality data.

Why did Curlew numbers change?

The analyses and detailed findings of the study can be found in the full paper in Bird Study. Here are the headlines:

- When all of the potential drivers of change were considered, the increase in wintering Curlew numbers across the whole of the UK during the 1980s and early 1990s is most likely to have been linked to the cessation of hunting.

- There has been a redistribution of Curlew over the period of the study, with a higher proportion of a reduced UK wintering population now wintering in the east. Many of the estuaries where numbers have been stable or there have been increases are on the east coast (including the Thames, Blyth, Tees and Alnmouth estuaries). Warmer winter temperatures may have made conditions in the east more suitable for wintering Curlew.

- Regional trends of wintering numbers were similar across the UK, although the exact timing of the post-hunting peak varied between regions. Numbers are still increasing in north-east England, the coldest region for which data were analysed.

- In addition to the reduction of direct mortality, Ian Woodward and colleagues suggests that the cessation of hunting may have led to reduced disturbance. Although wildfowlers will still have been shooting ducks and geese, they will not have been directly targeting areas with Curlew flocks.

- The research team did not detect an effect of changes in water quality, so it is unlikely that the clean-up of estuaries, prompted by the EU Water Framework Directive, had a major effect on the change in Curlew numbers.

- Curlew numbers decreased during winters with higher numbers of frost days but increased in the following years. An example of the dramatic effect of particularly cold weather was described by a wildfowler, operating on the Wash (Anglian region) in 1991, who came across a small flock of Curlew that had died where they stood, while roosting on the foreshore.

- In the paper, there is an extensive discussion about the factors that may lead to a redistribution of Curlew, after a period of cold weather. The authors suspect that local redistribution and behaviour changes, rather than long-distance movements, may be the main drivers of changes in annual numbers related to cold weather. Sadly, there is insufficient information to know what factors are at play. How many birds move out of areas to escape freezing conditions but then return to their old wintering areas in subsequent years? Is there a longer-term redistribution of some adults following a cold winter? Do new recruits take advantage of gaps left by missing birds in the winter after a cold-weather event? We need to know more about what happens to individuals in periods of extremely cold weather, which should be increasingly possible now that more Curlews are colour-ringed.

Read more

The analyses presented in the paper suggest that the period of increase, following the cessation of hunting, lasted for around 13 years. Since 1995, declines have resumed. We know that annual survival of the UK-wintering Curlew population is remarkably high, as discussed in another BTO paper by Aonghais Cook et al and described in More Curlew chicks needed. There is very strong evidence that conservation action to support this red-listed species needs to focus upon improving breeding season productivity.

Sadly, the best days for the UK’s wintering Curlew appear to be behind us, with a seemingly relentless decline in numbers since the winter of 1999-2000. This paper could not have been written without WeBS counters and, thanks to them, we will be able to discover what happens next.

The full Bird Study paper is:

Assessing drivers of winter abundance change in Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata in England and Wales. Woodward, Ian D., Austin, Graham E., Boersch-Supan, Philipp H., Thaxter, Chris B.and Burton, Niall H.K. Bird Study. https://doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2022.2049205

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton (@GrahamFAppleton) to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on published papers, with the aim of making shorebird science available to a broader audience.

Fight for Wonderful Biodiversity

Professor Salman Raza Senior Principal BS20 Government Degree College for Boys 7-D/2,North Nazimabad Karachi Pakistan College Education Department Government of Sindh Province Pakistan Professor of Zoology World Renowned Zoologist and Entomologist 🇵🇰🎖🎖

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: January to June 2022 | wadertales

Pingback: Wetland Bird Survey: working for waders | wadertales

Pingback: Is the Curlew really ‘near-threatened’? | wadertales

Pingback: WaderTales blogs in 2022 | wadertales