If you ask British birdwatchers to name the eleven wader species that are causing the most conservation concern in the UK, they would probably not include the Ringed Plover. Curlew may well be top of the list, even though we still have 58,500 breeding pairs in the UK*, but would people remember to include Ruff?

This blog was originally written to coincide with the publication of Red67, an amazing collaboration by artists and essayists that highlighted and celebrated the 67 species on the UK red list, nine of which were waders. Following the publication of the fifth edition of Birds of Conservation Concern on 1 Dec 2021, this blog has been revised, to include Dunlin and Purple Sandpiper. The UK Red List now contains 70 species.

*Avian Population Estimates Panel report (APEP4) published in British Birds

What’s a Red List?

The UK Red List is made up of a strange mixture of common and rare species. Nobody will be surprised to see fast-disappearing Cuckoo, Turtle Dove and Willow Tit, but why are 5.3 million pairs of House Sparrow in the same company? The list is very important because it helps to set the agenda for conservation action, the way that money for research is distributed and focuses attention during planning decisions. The main criteria for inclusion are population size – hence the inclusion of species that are just hanging on in the UK, such as Red-backed Shrike – and the speed of decline of common species. Data collected by volunteers, working under the auspices of the British Trust for Ornithology, measured a population decline for House Sparrow of 70% between 1977 and 2017, which is worrying enough to earn this third most numerous breeding species in the UK a place in Red67.

In his foreword to Red67, Mark Eaton, Principal Conservation Scientist for RSPB, explains how listing works. The Birds of Conservation Concern (BOCC) system, through which the Red List and Amber List are determined, uses a strict set of quantitative criteria to examine the status of all of the UK’s ‘regularly’ occurring species (scarce migrants and vagrants aren’t considered), and uses a simple traffic light system to classify them. There are ‘Red’ criteria with thresholds for rates of decline in numbers and range, historical decline and international threat (if a species is considered globally threatened it is automatically Red-listed in the UK), together with a range of other considerations such as rarity, international importance of UK populations, and how localised a species is. If a species meets any of the Red List criteria it goes onto the Red List.

The Red67 book – words meet art

Red67 was the brainchild of Kit Jewitt, a.k.a. @YOLOBirder on Twitter. It’s a book featuring the 67 Red-listed birds of Birds of Conservation Concern 4, each illustrated by a different artist alongside a personal story from a diverse collection of writers. Proceeds supported Red-listed species conservation projects run by BTO and RSPB. Kit describes Red67 as 67 love letters to our most vulnerable species, each beautifully illustrated by some of the best wildlife artists around, showcasing a range of styles as varied as the birds in these pages. My hope is that the book will bring the Red List to a wider audience whilst raising funds for the charities working to help the birds most at need.

This blog is about the nine waders in the book and the two additions to the list (Dunlin and Purple Sandpiper), but there are 58 other fascinating species accounts and wonderful artworks. Each species account starts with a quote from the story in the book and is accompanied by a low-resolution version of the artwork (Ringed Plover is illustrated above).

Lapwing

“It’s the crest that does it for me – that flicked nib stroke, the artist’s afterthought” – Lev Parikian

The Lapwing used to nest across the whole of the United Kingdom and was a common bird in almost every village. It’s still the most numerous breeding wader in the UK, with 97,500 pairs (APEP4), beating Oystercatcher by just 2,000 pairs. Numbers dropped by 54% between 1967 and 2017, according to BirdTrends 2019, published by BTO & JNCC. Huge losses had already occurred over the previous two centuries, as land was drained and vast numbers of eggs were collected for the table. The Lapwing is now a bird associated with lowland wet grasslands and the uplands, rather than general farmland.

Red-listing has been important for Lapwing, increasing the profile of the species and encouraging the development of specific agri-environment schemes targeted at species recovery. These include ‘Lapwing plots’ in arable fields and funding to raise the summer water tables in lowland grassland. Several WaderTales blogs describe efforts to try to increase the number of breeding waders in wet grassland, especially Toolkit for Wader Conservation. The loss of waders, and Lapwings in particular, from general farmland is exemplified in 25 years of wader declines.

Ringed Plover

“They gather at high tide like shoppers waiting for a bus: all facing the same direction, and all staring into the distance” – Stephen Moss

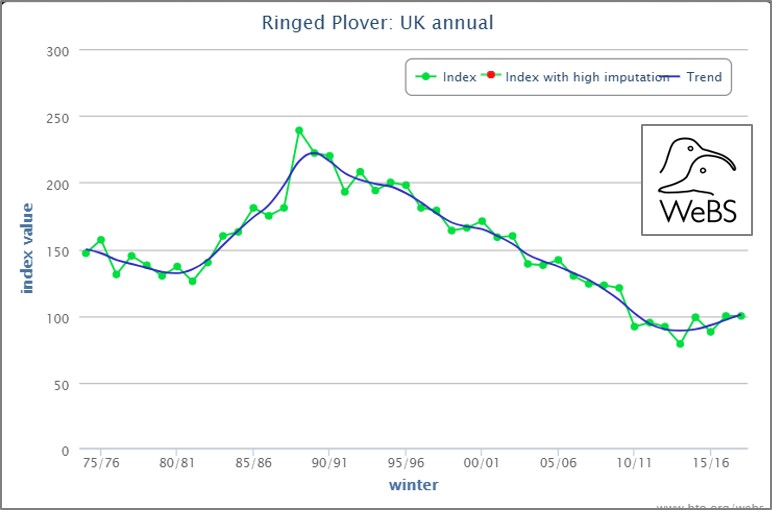

One of the criteria that the BOCC panel takes into account, when constructing the Red List, is the responsibility the UK has for a species or subspecies in the breeding season, during winter or both. The Ringed Plovers we see in the UK in the winter are almost exclusively of the hiaticula subspecies; birds that breed in southern Scandinavia, around the Baltic, in western Europe and in the UK. There are only estimated to be 73,000 individuals in this subspecies, so the 42,500 that winter in the UK constitutes a large percentage of the Ringed Plovers that breed in many of these countries.

The Wetland Bird Survey graph alongside shows a decline of over 50% between 1989 and 2014. At the start of the period, Ringed Plover numbers were at an all-time high but this is still a dramatic and consistent drop. Numbers have stabilised and may even have increased slightly but Ringed Plovers need some good breeding years. Disturbance is an issue for breeding Ringed Plovers, which share their beaches with visitors and dogs, and could also potentially be a problem in the winter (see Disturbed Turnstones).

Dotterel

“I want you in the mountains. Summer breeze. At home. Doing your thing. So don’t go disappearing on us, okay?” – Fyfe Dangerfield

The Dotterel is a much clearer candidate for Red67 – there’s a small population in a restricted area and numbers have fallen. The detailed reasons for decline may still need to be nailed down but candidate causes such as declining insect food supplies and the increasing numbers of generalist predators are probably all linked to a changing climate – squeezing Dotterel into a smaller area of the mountain plateaux of Scotland.

There’s a blog about the decline in Dotterel numbers called UK Dotterel numbers have fallen by 57%, based upon a paper that uses data up until 2011. At this point, the population was estimated at between 280 and 645 pairs. There has been no suggestion of improvement since that blog was written. Interestingly, Dotterel may have a way out of their predicament, as we know that marked individuals move between Scotland and Norway in the same breeding season. See also Scotland’s Dotterel: still hanging on.

Whimbrel

“How often do Whimbrels pass overhead nowadays? Unseen and unheard, their calls mean nothing to most of us” – Patrick Barkham

Most British and Irish birdwatchers think of Whimbrel as spring migrants, enjoying seeing flocks of Icelandic birds when they pause on their way north from West Africa (see Iceland to Africa non-stop). There is a small, vulnerable population nesting almost exclusively on Shetland. The latest estimate is 310 pairs (2009), down from an estimate of 530 pairs, published in 1997. Many pairs have been lost from Unst and Fetlar and this blog about habitat requirements might give clues as to why: Establishing breeding requirements of Whimbrel.

The curlew family is in trouble across the Globe, potentially because these big birds need so much space (see Why are we losing our large waders?)

Curlew

“… achingly vulnerable in a world that is battling to hold onto loveliness” – Mary Colwell

What more can be said about Curlew, ‘promoted’ to the red list in 2015 and designated as ‘near threatened’ globally. Most significant is the story from Ireland, where 94% of breeding birds have disappeared in just 30 years. These blogs provide more information about the decline and review some of the reasons.

- Is the Curlew really near-threatened?

- Curlews can’s wait for a treatment plan

- Ireland’s Curlew Crisis

- More Curlew chicks needed

There are more Curlew-focused blogs in the WaderTales catalogue.

Black-tailed Godwit

“A glimpse of terracotta is obscured by ripples of grass, dipping gently in the breeze” – Hannah Ward

Winter Black-tailed Godwit numbers are booming but these are islandica – birds that have benefited from warmer spring and summer conditions in Iceland, as you can read here in: From local warming to range expansion. Their limosa cousins are in trouble in their Dutch heartlands (with declines of 75%) and there have been similar pressures on the tiny remaining breeding populations in the Ouse and Nene Washes. Here, a head-starting project is boosting the number of chicks; so much so that released birds now make up a quarter of this fragile population. Red-listing has shone a spotlight on this threatened subspecies, attracting the funding needed for intensive conservation action.

Ruff

“They look a bit inelegant – a small head for a decently sized bird, a halting gait, and that oddly vacant face” – Andy Clements

There are two ways for a species to be removed from the Red List – extirpation (extinction in the UK) and improvement. Temminck’s Stint came off the list in 2015, having not been proven to breed since 1993, and Dunlin was moved to Amber at the same time. Ruff are closer to extirpation than they are to the Amber list. There is a spring passage, mostly of birds migrating from Africa to Scandinavia and the Baltic countries, and some males in glorious breeding attire will display in leks.

250 years ago, Ruff were breeding between Northumberland and Essex, before our ancestors learnt how to drain wetlands and define a hard border between the North Sea and farmland. Hat-makers, taxidermists and egg-collectors added to the species’ woes and, by 1900, breeding had ceased. The 1960s saw a recolonisation and breeding Ruff are still hanging on. There are lekking males causing excitement in sites as disparate as Lancashire, Cambridgeshire and Orkney, and there are occasional nesting attempts. Habitat developments designed to help other wader species may support Ruff but the situation in The Netherlands does not suggest much of a future. Here, a once-common breeding species has declined to an estimated population of 15 to 30 pairs (Meadow birds in The Netherlands).

Red-necked Phalarope

“… snatching flies from the water in fast, jerky movements, droplets dripping from its slender beak” – Rob Yarham

Red-necked Phalaropes that breed in Shetland and a few other parts of northern Scotland appear to be an overflow from the Icelandic population; birds which migrate southwest to North America and on to the Pacific coastal waters of South America. This BOU blog describes the first track revealed using a geolocator.

The Red-necked Phalarope was never a common breeder and came under pressure from egg-collectors in the 19th Century. Numbers are thought to have recovered to reach about 100 pairs in Britain & Ireland by 1920. Numbers then fell to about 20 pairs by 1990, so the latest estimate of 64 pairs (The Rare Breeding Birds Panel) reflects conservation success. Given the restricted breeding range and historical declines, it is unlikely that the next review will change the conservation status from Red to Amber, despite the recovery of numbers.

Woodcock

“… taking the earth’s temperature with the precision of a slow, sewing-machine needle” – Nicola Chester

The presence of Woodcock on the Red List causes heated debate; how can this still be a game species? Red-listing is indisputable; the latest survey by BTO & GWCT showed that there was a decline in roding males from 78,000 in 2003 to 55,000 in 2013, with the species being lost from yet more areas of the UK. Each autumn, the number of Woodcock in the UK rises massively, with an influx of up to 1.4 million birds. Annual numbers depend upon seasonal productivity and conditions on the other side of the North Sea. A recent report on breeding wader numbers in Norway, Sweden and Finland, shows that breeding populations of Woodcock in this area are not declining (Fennoscandian wader factory).

The UK’s breeding Woodcock population is under severe threat from things such as increased deer browsing and drier ground conditions but winter numbers appear to be stable. The difference in conservation status between breeding and wintering populations is reflected in the fact that Woodcock is on both the Red List and the Quarry List, for now. There is a WaderTales blog (Conserving British-breeding Woodcock) that discusses ways to minimizes hunting effects on British birds. These guidelines from GWCT emphasise the importance of reducing current pressures on British birds.

Dunlin (added to Red List 2021)

There are good reasons for the addition of Dunlin to the UK Red List; breeding numbers of the schinzii race have declined significantly and the number of wintering alpina Dunlin in the UK dropped 10,000 between two periods that were only eight years apart.

The fall in breeding numbers is probably the bigger problem, as indicated by range reductions in successive breeding atlas periods (1968-72, 1988-91 and 2008-11). It’s hard to monitor what is happening to numbers on a year-by-year basis because the breeding distribution is too patchy and thin to be picked up via the Breeding Bird Survey. Alarm bells are being raised in Ireland, where numbers have dropped to between 20 and 50 pairs (Status of Rare Breeding Birds across the island of Ireland, 2013-2018), and in the Baltic, where numbers have fallen by 80% since the 1980s. There’s a WaderTales blog about Finnish Dunlin.

The winter decline in the UK may or not be an issue, although it has to be considered as part of large-scale moderate losses across the whole of western Europe. There is a theory that, over the years, as winter conditions on the continental side of the North Sea have become less harsh, new generations of juvenile alpina have settled in countries such as the Netherlands, instead of continuing their southwesterly migrations from northern Russia. Once a wintering site has been chosen, individuals are site faithful, so one ends up with newer generations on the continent and ageing adults in the UK and Ireland. WeBS counts for Dunlin are half what they were 25 years ago.

Purple Sandpiper (added to Red List 2021)

The rocky coasts of the UK are home to Purple Sandpipers from the Arctic, with a suggestion that North Sea coasts, south of Aberdeen, mainly play host to birds from Spitsbergen and northern Scandinavia, with Greenlandic and Canadian birds more likely to be found further north and on the Atlantic coast. Coastal numbers declined by 19% between 1997/98 and 2015/16, according to the Non-estuarine Waterbird Survey, and WeBS counts suggest numbers have at least halved over a period of 25 years. The Highland Ringing Group has shown that the number of young Purple Sandpipers has been declining on the Moray Firth, suggesting either a period of relatively poor breeding success for birds migrating from the northwest or short-stopping by new generations of youngsters, as discussed for Dunlin. Perhaps they are wintering in Iceland these days?

In conclusion

The Red List creates some strange bedfellows. In the book, Turtle Dove follows Herring Gull; a bird with links to love and romance and another with at best the charm of a roguish pirate. But the List works; it creates an evidence-base that help those who devise agricultural subsidy systems, advise on planning applications, license bird control and prioritise conservation initiatives.

Red67 sought to raise awareness of the UK’s most at-risk bird species, nine of which were waders, and to raise money for BTO and RSPB scientists to carry out important research. It’s a lovely book that captures the thoughts and images of a generation of writers and artists. You can learn more about the project, order the book and buy some Red Sixty Seven products by clicking here.

Perhaps a second edition, called Red Seventy, might be produced, to reflect the changing fortunes of the UK’s birds? Worryingly, the first Red List, produced in 1990, only had 36 species on it.

Graham (@grahamfappleton) has studied waders for over 40 years and is currently involved in wader research in the UK and in Iceland. He was Director of Communications at The British Trust for Ornithology until 2013 and is now a freelance writer and broadcaster.

Pingback: Nine red-listed UK waders | wadertales

Reblogged this on Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: WaderTales blogs in 2021 | wadertales

Pingback: Curlew: after the hunting stopped | wadertales

Pingback: Wetland Bird Survey: working for waders | wadertales