When two legs are better than one: spring migration of Black-tailed Godwits.

The winter range of Icelandic Black-tailed Godwits covers a relatively wide latitudinal spread, from southern Spain to Scotland. Even though not at the extremes of this distribution, a flock of birds in Lisbon experiences very different mid-winter conditions to a flock of birds in Liverpool. December days never get shorter than 9hr 27min in Lisbon, which is 2 hours more than in Liverpool, and the average maximum daytime temperature is 14⁰C, as opposed to 6⁰C. On the negative side, it’s a lot further from Iceland to Portugal than it is to northern England.

The winter range of Icelandic Black-tailed Godwits covers a relatively wide latitudinal spread, from southern Spain to Scotland. Even though not at the extremes of this distribution, a flock of birds in Lisbon experiences very different mid-winter conditions to a flock of birds in Liverpool. December days never get shorter than 9hr 27min in Lisbon, which is 2 hours more than in Liverpool, and the average maximum daytime temperature is 14⁰C, as opposed to 6⁰C. On the negative side, it’s a lot further from Iceland to Portugal than it is to northern England.

In other studies (of Avocets and Cormorants, for instance) it has been shown that individual birds that winter close to their breeding areas are able to arrive back earlier in the spring than ones that winter further away. This is not the case in Black-tailed Godwits and this paper, published in Oikos in 2012, explains why.

Overtaking on migration: does longer distance migration always incur a penalty? José A. Alves , Tómas G. Gunnarsson , Peter M. Potts , Guillaume Gélinaud , William J. Sutherland and Jennifer A. Gill

Background

A team from the universities of East Anglia (UK), Iceland and Aveiro (Portugal) has been monitoring the spring arrival dates of colour-ringed Icelandic Black-tailed Godwits since 2000. The most recent paper to use this data-set has shown that adult birds have remarkably fixed arrival times in Iceland (to within a few days), and that the advancing arrival of the godwit population has been driven by young birds travelling to Iceland for the first time (see wadertales.wordpress.com/2015/11/16/why-is-spring-migration-getting-earlier). By tracking individual birds and the countries from which they travel, it is clear that the earliest arrivals are actually birds that winter in the southern part of the range – not the birds from northern and central parts of Great Britain, which have about 1500 km less far to travel.

For birds migrating south from arctic and subarctic breeding grounds, a trade-off might be expected between distance and conditions experienced during winter months. Birds travelling further south are likely to experience much more benign conditions, while those that undertake shorter flights expend less energy and may have the potential to return home earlier or to pick up clues as to the likely conditions they will face on breeding grounds in the early spring.

Work by Tómas Gunnarsson has shown links between arrival of Black-tailed Godwits in Iceland and subsequent breeding success. In areas where most territories are occupied early in the season, over half of pairs fledge youngsters whilst in areas where most territories are occupied later in the spring fewer than half of pairs are successful. You can read more here.

The easy life in Portugal

José Alves studied Icelandic Black-tailed Godwits wintering in Portugal as part of his PhD at the University of East Anglia. One of the papers from this work, focusing on energetics and migration strategies, was published in Ecology in 2013:

Costs, benefits, and fitness consequences of different migratory strategies. José A. Alves , Tómas G. Gunnarsson , Daniel B. Hayhow, Graham F. Appleton, Peter M. Potts , Guillaume Gélinaud , William J. Sutherland and Jennifer A. Gill

The paper shows that energetic conditions for wintering godwits are better in Portugal than further north in the winter range

- Warmer air temperatures and considerably lower wind speeds mean that thermoregulatory costs, and hence energetic requirements, are lower for godwits wintering in west Portugal than in south Ireland or east England.

- Black-tailed Godwits wintering in Portugal have access to larger numbers of bigger bivalves for the whole winter period. Birds wintering in eastern England or Ireland rarely find these big packages of protein.

- On average, foraging for c.5 hours per day provides sufficient intake for a Portuguese-wintering Black-tailed Godwit.

- In Ireland, the food supplies available on mudflats during the daylight hours of a tidal cycle are not sufficient, and godwits also forage on nearby grasslands.

- In eastern England, rapid depletion of food supplies on estuaries means that resources become very limited in late winter, and are often not sufficient to meet the energy requirements of wintering godwits.

Clearly, Portugal is a great place to spend the winter. It’s just a long way from Iceland.

The Spring Overtake

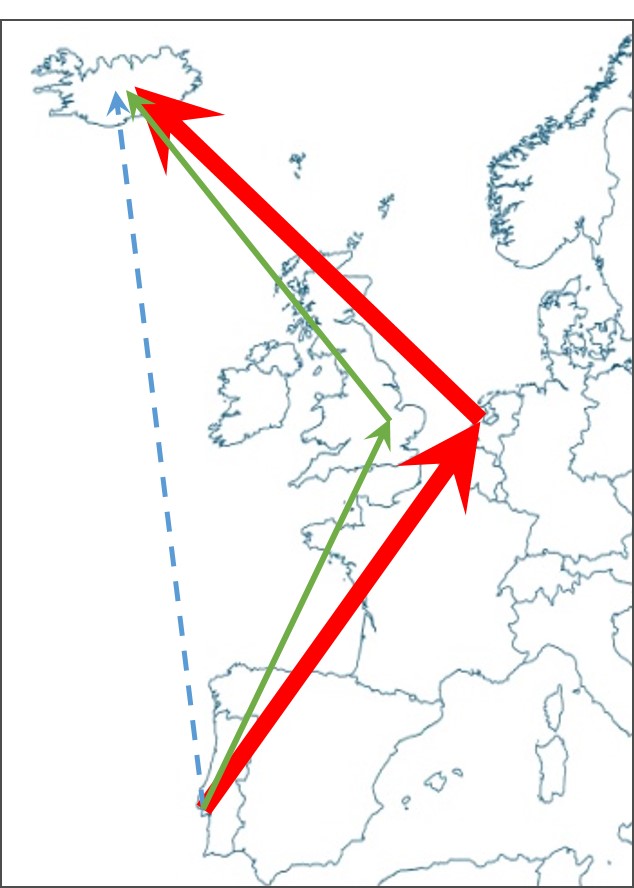

Portuguese Black-tailed Godwits travel further to their winter site but they break their spring migration into two legs, with most birds moving to the Netherlands in February or March and others staging in France, Great Britain and Ireland. By using Colin Pennycuick’s model ‘Flight’ (Pennycuick, C. J. 2008. Modelling the flying bird. – Academic Press), José Alves and his colleagues investigated the range of spring migration strategies available to individuals, given their body masses. Of Portuguese-wintering Black-tailed Godwits, around 10% are predicted to be able to reach the breeding grounds in one flight. From sightings of colour-ringed birds, it is clear that the vast majority of Portuguese birds do not make direct flights. It is possible that some individuals fly straight to Iceland but no bird has yet been proven to take this option.

When a small number of Black-tailed Godwits were caught in Portugal, just prior to the normal departure time, the masses of individuals were remarkably good predictors of their subsequent movements.

- The lightest male was predicted to be unable to reach even the first possible stop-over site, in France, and indeed this bird remained in Portugal throughout the breeding season.

- Of two males with just sufficient mass to reach France, one did indeed get to France and the other remained in Portugal during that breeding season (but did migrate the following year).

- The remaining seven males were predicted to be able to reach the major stop-over sites in the Netherlands or in east England (both of which are about 1750 km from west Portugal). Thanks to the wonderful network of observers, every one of these birds was spotted in these staging areas. These birds included RO-YGf (below)

- The only two females caught were both later recorded in the Netherlands; the heavier one was seen shortly after ringing and the lighter one arrived later, possibly having spent time in France.

Black-tailed Godwits are well watched and often deliver day-by-day records. For this species, colour-rings are a cheap and simple technology with which to study migration. You can read more about the network of colour-ring readers in the WaderTales blog, Godwits & Godwiteers.

The Oikos paper goes on to discuss the strategies being employed by Black-tailed Godwits, relating these to the importance of getting to Iceland early. You can read more here:

Overtaking on migration: does longer distance migration always incur a penalty? José A. Alves , Tómas G. Gunnarsson , Peter M. Potts , Guillaume Gélinaud , William J. Sutherland and Jennifer A. Gill

In Conclusion

Portuguese Black-tailed Godwits make full advantage of benign winter conditions in Portugal and then fly north very early in spring. By moving to the Netherlands (or Britain & Ireland) they are taking up pole position for the race to Iceland.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton, to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on previously published papers, with the aim of making wader science available to a broader audience.