There has been an assumption that managers of nature reserves know how to provide the right foraging conditions for Lapwing and Redshank chicks. This paper in Wader Study shows that they do.

How quickly will this Lapwing chick grow? Photo: Andy Hay/RSPB images

For conservationists looking to increase wader populations, attracting birds to a chosen site is a good first step, but only if pairs can breed more successfully than they would have done elsewhere. To understand whether a species recovery prescription works or, if it does not, to understand what is going wrong, it’s necessary to measure nest success, chick growth and fledging rates. In their paper in the journal Wader Study, Lucy Mason and Jen Smart focus on the middle of these – how well chicks grow – to check whether the right feeding conditions are being provided.

Tags make it easier to find ringed Redshanks. Photo: Kirsty Turner

Breeding success for Lapwing and Redshank can be poor, even on protected sites, which often leads site managers and policymakers to ask whether low food availability might be limiting chick survival, despite management aimed at providing optimum foraging conditions. Although this question is difficult to answer on a large scale, Lucy and her team were able to monitor and compare wader chick body condition and rates of growth across a range of UK sites. If food availability is an issue, they expected to find that chicks would grow slower and weigh less than might be expected – or hoped.

Photo: Kevin Simmonds

One of the main reasons RSPB scientists published this research was because site managers often ask for support to monitor invertebrates, in order to make sure that there is enough food for waders. There are lots of reasons why this is extremely difficult – i) what is enough? ii) chicks are catholic in their choice of prey, going for whatever is abundant and available at the time, so what do you measure and when? iii) linking food availability to growth and survival is inevitably tricky. The great thing about this paper is that it shows that, in general, well-managed sites will provide enough food. If managers are worried about food availability then monitoring the growth rates of chicks and comparing their data to the published information is far easier than measuring an invertebrate resource that varies hugely in space and time.

To understand the growth rates of Lapwing and Redshank chicks, a total of 130 tags were deployed across 15 lowland wet grassland nature reserves and protected sites, within the UK, during 2009, 2010, 2012 and 2013. This enabled family parties to be tracked and helped to yield a total of 750 monitored individuals. All sites were managed with the aim of providing optimum conditions for breeding Lapwing and Redshank (both nesting and chick rearing). Chicks were ringed, tagged and measured when captured and subsequently about every eight days. Relocating the chicks involved tracking the tagged individuals and, through them, their ringed siblings. It was harder to recapture Redshanks, which are more cryptically coloured and move around more.

Two well-grown Lapwings on a wet day. Photo: Jen Smart

Lucy and her colleagues demonstrated that, on average, Lapwing and Redshank chicks achieved growth rates similar to those calculated for larger samples of chicks studied in The Netherlands and the UK, and achieved better conditions more quickly than those measured in a standardised Dutch study. This suggests that food availability for wader chicks on well-managed lowland wet grassland sites is unlikely to be limiting chick survival and population recovery.

To understand why populations of species such as Lapwing and Redshank are failing to recover, the focus should be on other potential causes of chick mortality, such as predation or agricultural activities. The positive message is that, if these other causes of chick mortality can be reduced, well-managed wader sites are likely to be successful in producing healthy fledglings and to facilitate population recovery.

Body condition of tagged Lapwing chicks (centre) did not differ from that of untagged chicks in other broods, indicating that the tags (representing 2-3% of a tagged chick) and recapture frequencies did not aversely affect chick body condition or growth. Photo: Jen Smart

More feeding opportunities for chicks

There are several management options which are being used by conservation organisations and land-owners who are keen to try to support species that breed on lowland wet grasslands. The first suite increases feeding opportunities for chicks:

Long grass is important to nesting Redshank and their chicks. Photo Kevin Simmonds

Grazing regimes need to be adjusted to create the correct sward height, heterogeneity of structure etc. See, for instance, McCracken, D. & J. Tallowin. 2004. Swards and structure: the interactions between farming practices and bird food resources in lowland grasslands. Ibis 146: 108–114.

Increasing the height of the water table provides better feeding opportunities for adults and chicks. See, for instance: Eglington, S.M., M. Bolton, M.A. Smart, W.J. Sutherland, A.R. Watkinson & J.A. Gill. 2010. Managing water levels on wet grasslands to improve foraging conditions for breeding northern lapwing Vanellus vanellus. Journal of Applied Ecology 47: 451–458.

Providing more wet habitat features, in the form of pools or foot-drains. See, for instance: Eglington, S.M., J.A. Gill, M. Bolton, M.A. Smart, W.J.Sutherland & A.R. Watkinson. 2007. Restoration of wet features for breeding waders on lowland wet grassland. Journal of Applied Ecology 45: 305–314 and Smart, J., Gill, J.A., Sutherland, W.J., Watkinson, A.R., 2006. Grassland-breeding waders: identifying key habitat requirements for management. Journal of Applied Ecology 43: 454-463.

Using agri-environment schemes to achieve these habitat goals. See, for instance: Smart, J.A., Wotton, R., Dillon, I.A., Cooke, A.I., Diack, I., Drewitt, A.L., Grice, P.V. & Gregory, R.D. 2014. Synergies between site protection and agri-environment schemes for the conservation of waders on lowland wet grasslands Ibis 156: 576-590.

Reducing predation risks

A reduction in predation can be effected by direct control of species such as corvids, mustelids and foxes but other tools are also available:

Andy Hay/RSPB images

Removing isolated trees, telegraph posts and wires that are used as look-out perches by corvids: Berg, A., Lindberg, T. & Kallebrink, K.G. 1992. Hatching success of Lapwings on farmland – Differences between habitats and colonies of different sizes. J. Anim. Ecol. 61: 469-476 and MacDonald, M.A. & Bolton, M. 2008. Predation on wader nests in Europe. Ibis 150: 54-73.

Using electric fences to keep out foxes and badgers. Malpas, L. R., Kennerley, R. J., Hirons, G. J., Sheldon, R. D., Ausden, M., Gilbert, J. C. & Smart, J. 2013. The use of predator-exclusion fencing as a management tool improves the breeding success of waders on lowland wet grassland. Journal for Nature Conservation: 21, 37-47.

Designing the lay-out of water features so as to reduce fox/nest interactions: Bellebaum, J. & C. Bock. 2009. Influence of ground predators and water levels on Lapwing Vanellus vanellus breeding success in two continental wetlands. Journal of Ornithology 150: 221–230.

Diversionary feeding – providing areas of long grass which act as refuges for small mammals: see other WaderTales Blog.

Decisions for the future

Andy Hay/RSPB images

The majority of the chicks monitored in this study were predated before fledging. If this mortality can be reduced then sites which are managed with wader chicks in mind have the potential to support population recovery. Decisions upon how to reduce predation will need to be based upon the effectiveness and costs of the suite of solutions that are available, as well as ethical decisions as to which predators can be controlled and when – a potentially tricky issue for those managing nature reserves.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton, to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on previously published papers, with the aim of making wader science available to a broader audience.

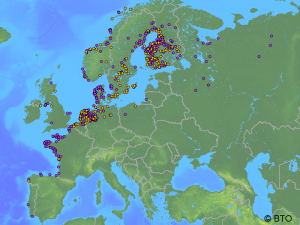

This year, we found far fewer waders than nine years ago. The table alongside provides a comparison for the three sections that we covered on Cumbrae for NEWS II and NEWS III. We failed to find any Purple Sandpipers in any of the 17 sections of the Clyde coast that we covered but were surprised to see a total of 5 Greenshanks. There seemed to be far fewer seabirds too. This is just a tiny snap-shot that may not be representative of the picture across the whole of the coastline of Britain & Ireland. Let’s hope that, despite the stormy weather, there was sufficient coverage for robust anlayses to be carried out by BTO staff.

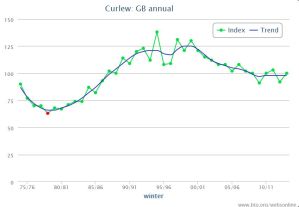

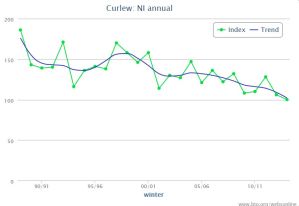

This year, we found far fewer waders than nine years ago. The table alongside provides a comparison for the three sections that we covered on Cumbrae for NEWS II and NEWS III. We failed to find any Purple Sandpipers in any of the 17 sections of the Clyde coast that we covered but were surprised to see a total of 5 Greenshanks. There seemed to be far fewer seabirds too. This is just a tiny snap-shot that may not be representative of the picture across the whole of the coastline of Britain & Ireland. Let’s hope that, despite the stormy weather, there was sufficient coverage for robust anlayses to be carried out by BTO staff. We know that wader number on estuaries are changing. For instance, in the last few years, numbers of Ringed Plover in the UK have been falling (see figure). The declining line indicates a significant drop but it won’t be quite such a concern if this year’s NEWS-III surveyors find that there are now more Ringed Plovers on open coasts. That may seem like an optimistic suggestion, unless you look at changes between NEWS (1997/98) and NEWS-II (2006/07). During this period, at the same time that WeBS counts of estuaries were falling, there was actually a 25% increase in Ringed Plover numbers on open coast. Perhaps this redistribution from estuaries to open coasts has continued?

We know that wader number on estuaries are changing. For instance, in the last few years, numbers of Ringed Plover in the UK have been falling (see figure). The declining line indicates a significant drop but it won’t be quite such a concern if this year’s NEWS-III surveyors find that there are now more Ringed Plovers on open coasts. That may seem like an optimistic suggestion, unless you look at changes between NEWS (1997/98) and NEWS-II (2006/07). During this period, at the same time that WeBS counts of estuaries were falling, there was actually a 25% increase in Ringed Plover numbers on open coast. Perhaps this redistribution from estuaries to open coasts has continued? Twenty-one species of wader were recorded during NEWS-II, with Oystercatcher being the most numerous with an estimated total of 64,064 for the whole non-estuarine coastline of the UK.

Twenty-one species of wader were recorded during NEWS-II, with Oystercatcher being the most numerous with an estimated total of 64,064 for the whole non-estuarine coastline of the UK.

Colour-ringed Icelandic Oystercatchers are part of a new project to look at how climate change might be affecting migration patterns.

Colour-ringed Icelandic Oystercatchers are part of a new project to look at how climate change might be affecting migration patterns.

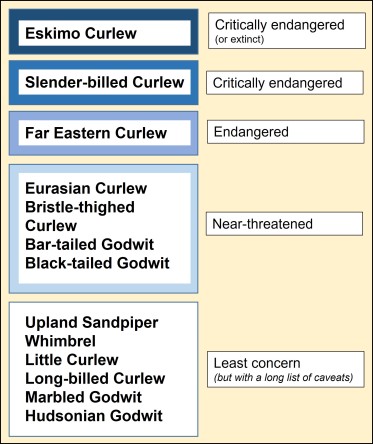

Thirty years ago there were eight members of the world-wide curlew family but now we may well be down to six. The planet has lost one species, the Eskimo Curlew, with no verified sightings since the 1980s, and probably the Slender-billed Curlew as well. Of the others, Far Eastern Curlew and Bristle-thighed Curlew are deemed to be endangered and vulnerable**, respectively, and our own Curlews are classed as near-threatened, which is the next level of concern. This may seem strange, especially when flocks of 1000 can be seen on the Norfolk coast. However, evidence suggests that we should take heed of what is happening to other members of the curlew family, as we consider the future of this evocative species with its wonderful bubbling curl-ew calls.

Thirty years ago there were eight members of the world-wide curlew family but now we may well be down to six. The planet has lost one species, the Eskimo Curlew, with no verified sightings since the 1980s, and probably the Slender-billed Curlew as well. Of the others, Far Eastern Curlew and Bristle-thighed Curlew are deemed to be endangered and vulnerable**, respectively, and our own Curlews are classed as near-threatened, which is the next level of concern. This may seem strange, especially when flocks of 1000 can be seen on the Norfolk coast. However, evidence suggests that we should take heed of what is happening to other members of the curlew family, as we consider the future of this evocative species with its wonderful bubbling curl-ew calls.