To help to take the pressure off declining and now red-listed British-breeding Woodcock, many estates are already delaying the start of the Woodcock shooting season. How might this make a difference?

This is a modified version of an article published in Shooting Times on 30 Sep 2015. There are updates at the end, reflecting changing advice provided by the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust.

Each autumn, the British population of Woodcocks is swamped by the arrival of up to a million birds, returning from northern Europe and Scandinavia. The exact timing of their migration is very much influenced by weather, with birds crossing the North Sea as early as October or as late as December. The numbers each year are thought to vary markedly, reflecting peaks and troughs in the size of the European breeding population, annual chick production, the amount of frost and snow on the other side of the North Sea and the timing of periods of cold weather.

A quick look at the bag index for Woodcock, produced by the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT), shows annual variation in the numbers shot each winter but no downwards trend. Hunting appears to be sustainable (but see note at the bottom giving advice from GWCT about shooting in winter of 2017/18). Unfortunately, there is a problem; British-breeding Woodcock are in serious decline and there is no way to differentiate between a local bird and one from continental Europe. As the GWCT Woodcock tracking project has shown, birds share the same woodland habitats during winter months. Mara and Jack, for instance, two birds caught in March 2014 on Islay, have very different annual stories to tell, with Mara breeding locally and Jack migrating to Russia.

A shrinking distribution

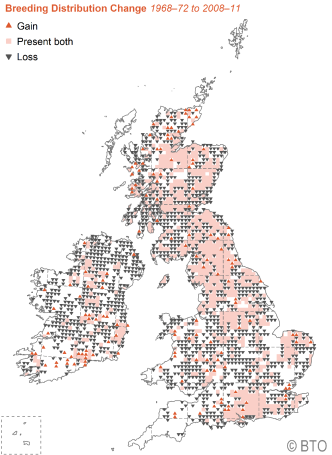

Bird Atlas 2007-11, published by the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), confirmed that our Woodcock are in trouble. Between 1968-72 and 1988-91, the number of 10×10 km atlas squares where Woodcock were present fell from 1439 to 917, representing a decline of 36%. By 2008-11, the number was down to 632, a further drop of 31%. In the 1968-72 Atlas, Woodcocks were generally widespread, with birds absent only from parts of southwest England and Wales and easy to find from the North Midlands through to northern Scotland, other than in the highest mountains. Fragmentation that was becoming apparent in 1988-91 was glaringly obvious in 2008-11, especially in the south and west. In Ireland the situation, if anything, looked worse.

Bird Atlas 2007-11, published by the BTO, in association with the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club and BirdWatch Ireland, shows that breeding Woodcock are disappearing from southern and western Britain, as well as from Ireland. Downwards pointing black arrows show losses.

Early results being contributed to the Bird Atlas 2007-11 project confirmed that there was an urgent need for a special Woodcock survey, to try to assess numbers as well as distribution, and this was organised for the summer of 2013. The GWCT and the BTO wanted to replicate the survey they had organised in 2003, which suggested that the breeding population across Scotland, Wales and England included just over 78,000 territorial males.

Andrew Hoodless of GWCT has shown that the number of Woodcocks observed during a standard evening watch period provides a good index of local abundance. The national survey called for the deployment of hundreds of birdwatchers, who were asked to visit chosen sites, many of which had been visited ten years previously. Standing at dusk and listening to the distinctive roding calls of male Woodcocks, as they patrol the boundaries of their territories, provides magical moments for lucky birdwatchers. However, the chance of success in many parts of the country was far lower in 2013 than it had been in 2003. A paper, with a full regional analysis was published in 2015, revealing an estimated fall in numbers of 30%, to just over 55,000 roding males. As suggested by the Atlas distribution maps, percentage losses were higher in Wales and England than in Scotland.

The main aim of the 2013 Woodcock survey was to assess the population, rather than to understand the causes of decline, but it is interesting to note that there were smaller losses in the largest areas of woodland. More detailed studies have suggested that larger woods may offer a greater diversity of habitats and damper micro-climates in which to feed. Booming deer populations are having major effects on a lot of woodlands; by browsing the vegetation they can open up the understorey, thereby removing nesting habitat and drying out soils. There are probably several factors driving down the breeding population and it has been suggested that recreational disturbance and over-winter hunting of resident birds could each be playing a part in declines.

Changes to the hunting season?

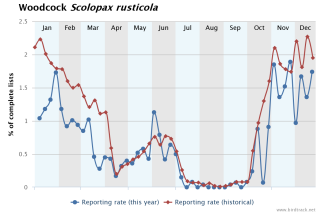

BirdTrack is coordinated by the BTO, in partnership with RSPB, BirdWatch Ireland, the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club and the Welsh Ornithological Society. These lists provide fascinating information about the timing of migration, annual breeding patterns and species’ abundance. See www.birdtrack.net to learn more.

Although the main pressures may well occur during the summer months, one way to help British breeding Woodcock may be to change the start of the shooting season. The season currently opens on 1 September in Scotland and 1 October across the rest of the UK.

Looking at BirdTrack data, collected from species lists sent in by thousands of birdwatchers across Britain & Ireland, it is clear that there are virtually no continental Woodcock in these islands during September and few until at least the second half of October. In the graph alongside, the red line shows average rates of occurrence on birdwatchers’ lists. The blue line for 2014 indicated a pulse of arrivals in early October, largely as observed by birdwatchers on the east coast. These birds will have moved inland and disappeared into woodland and farmland. The main arrival in this particular year appears to have been in late October with later spikes in the graph suggesting further bursts of east coast activity in November and December.

The 2013 Woodcock survey was funded by the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust, the Shooting Times Woodcock Club and a charitable trust. Photo: Richard Chandler

The BirdTrack pattern will come as little surprise to gamekeepers and shoot-owners, many of whom already restrict Woodcock shooting to the winter months, in order to minimise losses of local, resident birds. GWCT scientists have been encouraging restraint in the autumn months for some while. Now, having analysed the results of the GWCT/BTO 2013 Woodcock survey, and shown a further decline of nearly a third in just ten years, they are researching the potential impact of shooting on resident birds. This will include an assessment of whether a formal change to the timing of the hunting season for Woodcock is required, in order to add an extra level of protection to resident birds.

Update: 28 July 2017

New GWCT guidance: ‘generally we recommend not shooting woodcock before 1 December’ and not at all if ‘numbers have been low in the area’. More information is available at https://www.gwct.org.uk/media/696047/Pocket-woodcock-guide.pdf

Update: 11 December 2017

Migrant Woodcock appear to have had a poor breeding season and GWCT is advising restraint:

Dr Hoodless has issued the following statement: “GWCT and the Woodcock Network are advising shooters across the UK to rethink their woodcock shooting for this season and reduce their bags. This echoes moves being taken by organisations in several other European countries. A further update will be issued in early January, once more information is available.”

“Although similar events will have happened many times in the past, this is the first time that monitoring of woodcock age ratios by ringers, and improved communication across Europe, has been able to offer shooters an early warning system. Populations normally rebound after such events, but most shooters understand the importance of preserving breeding stocks when there are signs of adverse natural events and are prepared to minimize shooting pressure in order to aid population recovery.”

Update: 16 March 2018

Woodcocks are severely affected by cold weather. Research by GWCT suggest that Woodcock start to suffer when the ground has been frozen for relatively short periods of time. They propose restraint after four days of freezing conditions, with birds being given a recovery period of seven days once a thaw commences. There’s more in this blog here and the paper can be found here.

Update: September 2020

There is no suggestion that the numbers of Woodcock breeding in Finland, Sweden and Norway are changing. This blog summarises survey data for breeding waders during the period 2006 to 2018.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton, to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on previously published papers, with the aim of making wader science available to a broader audience.

Very nice blog!

LikeLike

very informative read and brought back unhappy memories of negative surveys locally with no woodcocks but plenty of mosquitoes !!

LikeLike

Pingback: What’s in WaderTales – so far? | wadertales

Pingback: WaderTales: a taste of Scotland | wadertales

Pingback: Wales: a special place for waders | wadertales

Pingback: Which wader, when and why? | wadertales

Pingback: Talking to Shooters – Graham Appleton – James Common

Any way I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you post again soon. I don’t think I could have put it better myself.

LikeLike

Pingback: The waders of Northern Ireland | wadertales

Pingback: Do population estimates matter? | wadertales

Pingback: Fennoscandian wader factory | wadertales

Pingback: Nine red-listed UK waders | wadertales

Pingback: The First Five Years | wadertales

Pingback: Eleven waders on UK Red List | wadertales

Pingback: UK waders: “Into the Red” | wadertales