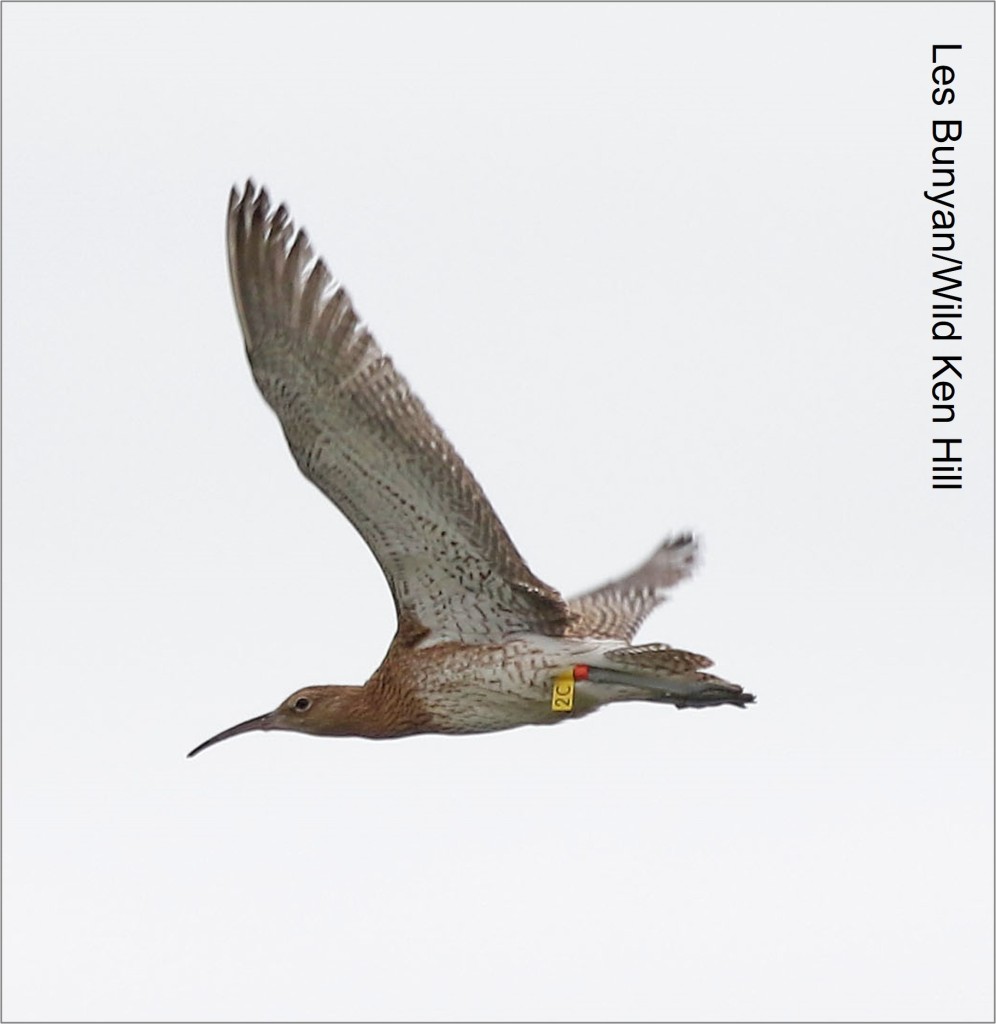

83 captive-reared Curlew were released successfully in 2019, over 130 in 2021 and a similar number in 2022 but this does not mean that head-starting is a solution to England’s Curlew problems. We don’t yet know the proportion of youngsters that survive the difficult ‘teenage years’, how many will find suitable breeding habitat and whether these birds can reliably raise chicks of their own. What have birds such as 7K, pictured here, revealed and what might happen next?

Exciting news

There has been some great TV and press coverage of head-started Curlew this summer (2022), with films of captive-reared birds being released from pens and flying for the first time. But what does the future hold for naïve birds that take to the air in Shropshire & Powys, the Severn & Avon Valleys of western England, Cornwall, Sussex and Norfolk? The first signs are good, as illustrated below in maps published by the BTO for the birds that they are tracking in Norfolk.

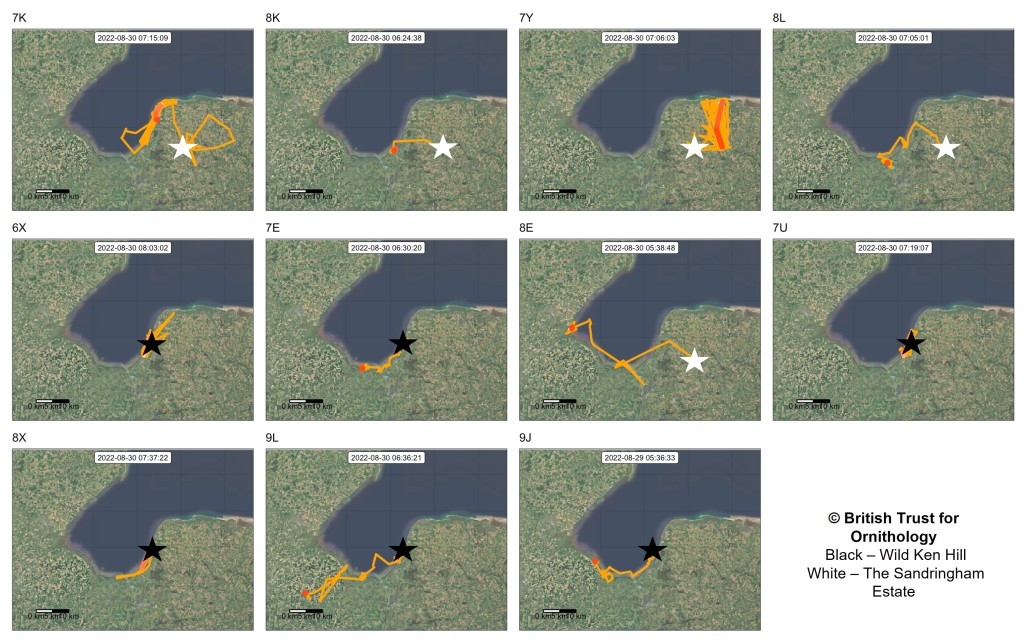

Satellite-tagged birds released at Ken Hill (Black stars – close to the Norfolk coast) can be seen flipping backwards and forwards between the mudflats and their release site, before beginning to explore more of the Wash estuary.

Birds released further inland, on The Sandringham Estate (White stars), started foraging in grassland areas and it took a while until any of these birds discover the coast. One bird “7Y” moved onto a little-used airfield (below), where it was seen with a flock of adults. It appears to have adopted a mudflat/grassland tidal routine, involving ‘commutes’ of ten miles each way, possibly having been guided by the adults (top row, third from the left).

It is easy to get ‘wowed’ by the TV reports and the individual stories of tracked birds but these are early days for Curlew head-starting. There’s a lot still to learn!

Why head-start Curlew chicks?

The Eurasian Curlew is in trouble, as you can read in the WaderTales blog “Is the Curlew really near-threatened?”. Annual survival rates of adults are high but productivity is low, with an estimate of 10,000 too few youngsters being fledged each year, to maintain population levels in the UK. The Irish Curlew population has crashed, providing dire warnings of what may happen soon in Wales, where there has been a decline of 73% since 1995 (Breeding Bird Survey). In southern England, most of the losses happened before 1995 and only a few populations remain, hanging on in areas such as Breckland in East Anglia.

Lessons from Black-tailed Godwits

We know that head-starting works well for limosa Black-tailed Godwits breeding in East Anglia but there was no guarantee that this would be the case when the WaderTales blog Special Black-tailed Godwits was published in 2017, to coincide with the departure of captive-reared birds from their WWT Welney release site. When the first birds not only returned in 2018 but actually raised their first chicks (see Head-starting Success), the approach looked to be successful. Over the following years, with more releases, the godwit population in the Ouse and Nene Washes has increased significantly. This temporary relief package for a beleaguered population has worked well, providing time to try to improve breeding conditions in the wild, so that Black-tailed Godwits can look after themselves. Head-starting is an intervention of last resort and cannot be a long-term solution to the problems faced by the species.

It is possible to support local populations of scarce birds, such as Bitterns and Little Terns, with interventions such as increasing areas of suitable habitat and protecting nest sites, but doing the same for Curlew will be more of a problem. Here, the challenge is to halt a decline of a species that breeds across wide areas of the UK, mostly on farmed land that is not being managed for conservation. Intensive, local action is not going to be enough. This is going to need teamwork between landowners, conservation organisations and volunteers – acting at a scale that has not been tried previously. Perhaps head-starting will help?

A pragmatic plan

The most recent UK population assessment of Curlew, in British Birds, suggested that there were 58,500 breeding pairs in 2016. Numbers have almost certainly dropped since then but the species is nowhere near as threatened as England’s breeding Black-tailed Godwits. The biggest Curlew head-starting programme, led and funded by Natural England, was a response to an opportunity to use unwanted Curlew eggs – not a ‘last-chance’ solution, as it had been for Black-tailed Godwits. Each year, Curlew eggs were being collected on RAF airfields, under licence, to deter adults and reduce airstrike risk. Thanks in no small part to Natural England’s Graham Irving, many of these eggs are now being head-started, instead of destroyed.

What happens to head-started birds?

The Natural England project builds upon the experiences of the Curlew Country team, working in the Shropshire hills and Powys borders. They released 6 head-started Curlew in 2017, 21 in 2018, 33 in 2019 and 34 in 2021. Raising extra chicks is part of an initiative that involves a broad range of stakeholders. See their website for more information.

The first stage of the head-starting process works well. Aviculturalists can rear and release chicks, with very high rates of success. They are learning more and more about the best diets, appropriate husbandry and the release process. Individual chicks wear small colour-rings, so that progress can be monitored daily, and they receive leg-flags and get weighed and measured before release. For instance, the young Curlew 7K featured above is a GPS tagged male that weighed in at a respectable 550 grammes when it was transferred to its release site on The Sandringham Estate, on 14 July 2022. By the end of August, it had moved to the Wash Estuary, as you can see in the figure above (top left map). There was a December report of 7K from a piece of amenity land on the edge of a new housing development in Hunstanton.

From the start, the Natural England project has been built on partnerships. In the first year (2019), eggs were hatched and chicks were reared at WWT Slimbridge. Fifty young Curlew were released near-by and the first of these birds (wearing ring number 23) was found nesting near Gloucester in 2021, raising one chick of his own. In 2022, three years after release, five of the head-started Curlew were on breeding sites in the Severn and Avon area and one bird had moved to the Thames Vale. Male “23” shows that head-starting can add more Curlews to the breeding population but is he exceptional? What proportion of released birds make it this far and go on to raise chicks? The video by Kane Brides in this WWT blog tells the West Country story so far.

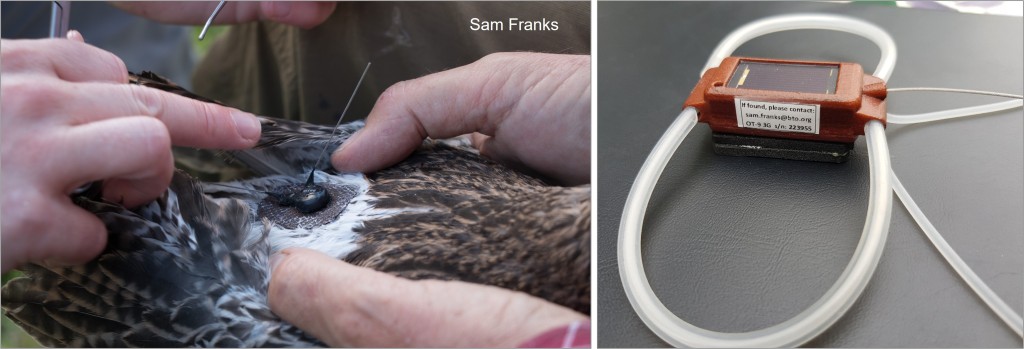

After a Covid-caused hiatus in 2020, the head-starting project expanded in 2021, with birds reared at both WWT Slimbridge in Gloucestershire and Pensthorpe in Norfolk. Richard Saunders, the Senior Ornithologist for Natural England, recognised the importance of learning what happens to newly-released fledglings and of monitoring potential recruitment. Working with Sam Franks of BTO and with lots of support from others, the Pensthorpe-reared Curlews are starting to reveal some of their secrets.

Where will the Pensthorpe birds set up home?

Most waders are philopatric; when they look for breeding sites, they tend to return to places close to the places in which they were raised. The release sites in North Norfolk were chosen not only because they provided suitable conditions for growing teenage waders, with low predator numbers and adults feeding nearby, but also because they are relatively close to current breeding sites, such as Roydon Common and the heaths of Breckland (see Curlews and foxes in East Anglia). There are also airfields, of course, and it will be unfortunate if birds choose these sites, given that eggs were removed to try to reduce bird-strike risk.

All of the chicks are colour-ringed, some of them are radio-tagged and others are GPS-tagged, prior to release. By following tagged birds, as they explore the area around the release sites, the project aims to understand more about habitat use and to see if these naïve birds seem unduly prone to predation, given that they have not been trained to look out for danger by watchful parents. GPS tagging helps to paint the bigger picture; would birds move to the mudflats of the Wash and spend the whole winter in Norfolk or would some move on, to southern England, Ireland or France, for instance? These data will hopefully be augmented by reports of colour-ringed birds that do not carry tags.

The first results have been encouraging. For example, a GPS tagged female from the first cohort released in Norfolk in 2021, wearing flag 0E, has followed the ‘stay local’ option. She spent the winter on the saltmarshes of RSPB Frampton, on the Wash in Lincolnshire, and has largely stayed on the south shore of the Wash through her first summer, showing no evidence of visiting any type of breeding habitat yet. A male Curlew wearing flag 4P has been more adventurous, spending the winter on the Exe Estuary in Devon, a site used by some adult Curlews that breed in Eastern England.

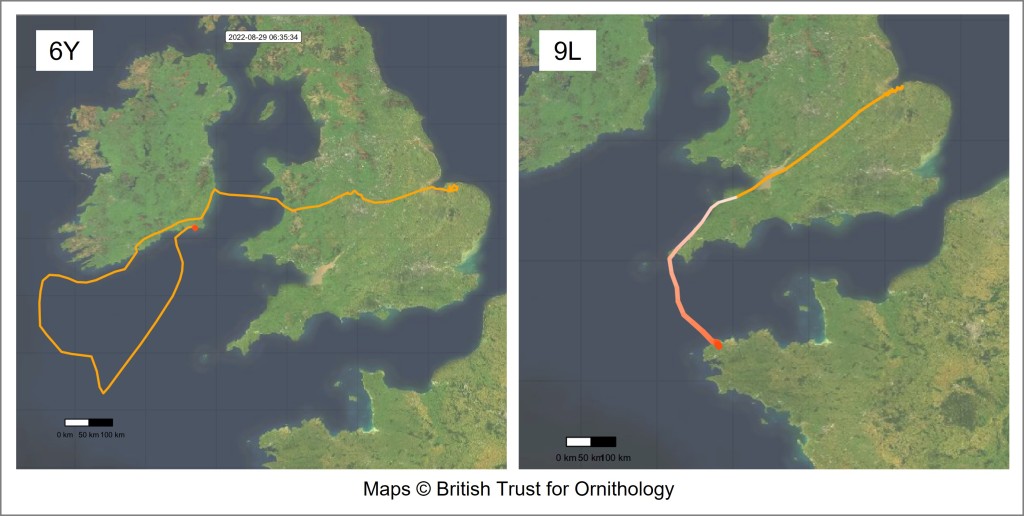

The amazing left-hand map below shows the route taken by ‘6Y’, one of the first batch of 2022 birds to be released on The Sandringham Estate. The story of this bird is told by the BTO’s Dr Sam Franks:

“The first of this year’s birds to migrate away from Norfolk departed at sunset last Wednesday & arrived on a Staffordshire field at sunrise on Thursday. It then flew towards Ireland & made an anxiety-inducing trip out into the Atlantic before returning to dry land.”

The right-hand map shows an overnight flight by ‘9L’, one of the last birds to be released from Ken Hill. This bird, pictured to the right , set off on the evening of 16th September, flew southwest overnight and headed south when it ran out of land. It landed in France at 01.30 on 17th. Although there is supposed to be a Curlew hunting ban in France (see this blog), three satellite-tagged birds from elsewhere in Europe were shot in the first weekend of the 2022 autumn hunting season. Will 9L survive the winter?

Data generated by colour-ring sightings will be analysed to check whether annual survival of youngsters in their first couple of years are consistent with figures for wild-reared chicks. This follow-up work is really important – the head-starting operation may seem to be successful but if few chicks survive long enough to breed then alternative approaches may be needed. Sightings of colour-ringed birds provide important information to add to data collected from tagged birds, which means that there is a vital role to be played by birdwatchers.

Around England

People care deeply about Curlew, as Mary Colwell explored in a recent book, reviewed in the WaderTales blog Curlew Moon, so it is not surprising that landowners feel inspired to help the species, by releasing birds on their own land. An attempt is being made to boost a tiny population on Duchy of Cornwall land on Dartmoor, using eggs from East Anglian airfields that were hatched at Slimbridge, and a licence has been granted to take eggs from a site in Northern England to be reared in Sussex, on an estate that appears suitable but where Curlew do not currently breed.

Release sites for these translocated birds do not hold many (or even any) Curlew so it will be interesting to learn whether the behaviour patterns of these fledglings are different to those of birds released in Norfolk and in the Severn and Avon Valleys of western England. All birds are being ringed, by WWT, GWCT and BTO ringers, with every report of a marked bird adding to our understanding of the success of the various projects. In each case, hopefully there will be enough money to deploy dedicated fieldworkers to monitor what happens to the released birds during the crucial first few weeks of independence, so that fledging rates can be accurately assessed, and to monitor return rates in subsequent breeding seasons. For slow-maturing birds, this follow-up work will involve a five-year commitment.

Maximising effectiveness

The work being funded by Natural England in East Anglia is expensive. It will be judged as successful if released birds augment local populations, whether these be in East Anglia (as hoped) or in another part of lowland England. If birds choose to breed in the North of England, where numbers are still high, or even overseas, then that may make it difficult to justify the expense of further rearing and monitoring work.

There is a concern that head-starting will be seen as a solution to the problems being faced by Curlew. It isn’t! The estimated shortfall in fledged chicks is 10,000 birds per year, across the whole of the UK, and head-starting will never make a big impact on that number. It may be a way to boost numbers in lowland areas, from which the species would otherwise be lost, but only if the conditions for successful breeding can be created and maintained. This means tackling the thorny problems of habitat degradation and predator numbers. Head-starting may seem like a dynamic intervention but if birds are released into areas where breeding success is too low then it’s not going to produce a sustainable solution to the problems being faced by England’s Curlew.

The Norfolk head-starting project would appear to tick all the right boxes – release sites with low predator numbers, right next to an estuary with lots of Curlew and with successful breeding sites near-by. Head-started birds soon start to explore the mixture of arable and tidal resources available to them and it looks as if early-years survival rates might be as high as expected of wild-reared birds. Despite all these positive signs, it will be a couple of years until this year’s young Curlew start breeding – somewhere – and that will be the crucial test of head-starting. Meanwhile, it is hoped that birdwatchers will look out for colour-ringed birds, so that survival rates can continue to be monitored. Every Curlew counts!

Norfolk-ringed head-started Curlew wear yellow flags, each with number & letter, immediately above an orange ring. Please report sightings of colour-ringed head-started Curlew using THIS LINK.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton (@GrahamFAppleton) to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on published papers, with the aim of making shorebird science available to a broader audience.

Thirty years ago there were eight members of the world-wide curlew family but now we may well be down to six. The planet has lost one species, the Eskimo Curlew, with no verified sightings since the 1980s, and probably the Slender-billed Curlew as well. Of the others, Far Eastern Curlew and Bristle-thighed Curlew are deemed to be endangered and vulnerable**, respectively, and our own Curlews are classed as near-threatened, which is the next level of concern. This may seem strange, especially when flocks of 1000 can be seen on the Norfolk coast. However, evidence suggests that we should take heed of what is happening to other members of the curlew family, as we consider the future of this evocative species with its wonderful bubbling curl-ew calls.

Thirty years ago there were eight members of the world-wide curlew family but now we may well be down to six. The planet has lost one species, the Eskimo Curlew, with no verified sightings since the 1980s, and probably the Slender-billed Curlew as well. Of the others, Far Eastern Curlew and Bristle-thighed Curlew are deemed to be endangered and vulnerable**, respectively, and our own Curlews are classed as near-threatened, which is the next level of concern. This may seem strange, especially when flocks of 1000 can be seen on the Norfolk coast. However, evidence suggests that we should take heed of what is happening to other members of the curlew family, as we consider the future of this evocative species with its wonderful bubbling curl-ew calls.