If Norwegian Oystercatchers migrate south and west for the winter, how is it that thousands of Oystercatchers can adopt a stay-at-home strategy in Iceland, which lies at a higher latitude than most of Norway?

Braving the cold

As part of a project to try to understand why some Oystercatchers spend the winter in Iceland, when most fly south across the Atlantic, researchers needed to count the ones that remain. Unlike in the UK, where the Wetland Bird Survey can rely on over 3000 volunteers to make monthly counts of waders and waterfowl, it’s tough to organise coordinated counts of waders in Iceland. Winter weather, a small pool of birdwatchers and short days don’t help when you are trying to cover the coastline of a country the size of England.

Up until 2016, the only winter wader data in Iceland came from Christmas Bird Counts, first run in 1956. These coordinated counts suggested that most Oystercatchers were to be found in southwest and west Iceland, which is also where most birdwatchers live, but with smaller numbers in areas such as the southeast. The maximum number of Oystercatchers found in any one year was 4466 birds but this excluded known wintering sites which were inaccessible or very hard to access. Some contributors to Christmas bird counts live in areas away from the well-populated west of the country, and they provided evidence that there were no Oystercatchers in the north, for instance. This information gave some guidance as to where to look for Oystercatcher flocks but could a small team of researchers and birdwatchers do a complete count of the resident component of the species in the middle of winter?

Part one of the survey involved a group of well-prepared birdwatchers and researchers spending several days counting Oystercatchers in as many areas as possible of the southeast and in the whole of the west, from the southwest tip of Iceland (where Keflavik airport is situated) through to known wintering locations in the northwest fjords. The north and south coasts could largely be discounted; the north is too cold and the south coast is very barren.

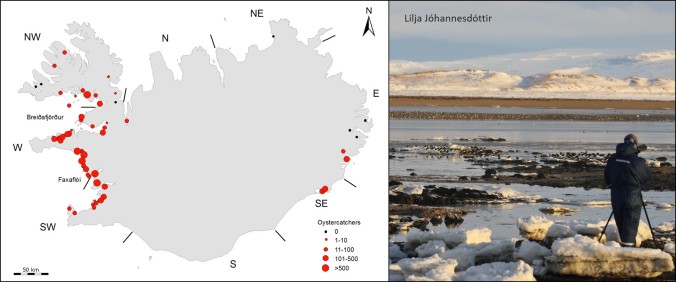

Part two of the survey was carried out by air, allowing the addition of counts of the islands and inaccessible coastal sites in the Breiðafjörður Bay, as well as some key sites in Faxaflói Bay (see map). Flocks of roosting Oystercatchers were usually seen from afar and photographs were used to make counts without flushing the birds.

Survey results

The ground-based wader surveys were carried out between 28 January and 3 February 2017 and the aerial survey took place on 16 February. In total, 11,141 Oystercatchers were counted, which nearly triples the previous Christmas total. As expected, the vast majority of Oystercatchers were found on wintering sites in SW and W Iceland. Large numbers of birds were found on sites not covered by the Christmas counts, particularly on the north side of Faxaflói Bay and during the aerial survey over Breiðafjörður Bay.

The full results of the paper are presented in a new paper in the BTO journal Bird Study. (Click on title for link)

The full results of the paper are presented in a new paper in the BTO journal Bird Study. (Click on title for link)

Population size of Oystercatchers Haematopus ostralegus wintering in Iceland Böðvar Þórisson, Verónica Méndez , José A. Alves, Jennifer A. Gill , Kristinn H. Skarphéðinsson, Svenja N.V. Auhage, Sölvi R. Vignisson, Guðmundur Ö. Benediktsson, Brynjúlfur Brynjólfsson, Cristian Gallo, Hafdís Sturlaugsdóttir, Páll Leifsson & Tómas G. Gunnarsson.

Resident or migrant?

One of the key questions that researchers wanted to answer was ‘what proportion of the Icelandic breeding population is migratory?’ This is part of a bigger project exploring the causes and consequences of individual migratory strategies, as you can read in the previous WaderTales blog: Migratory decisions for Icelandic Oystercatchers. This project is a joint initiative by the universities of Iceland, East Anglia and Aveiro, led by Verónica Méndez.

In order to estimate the proportion of migrants and residents it was necessary first to determine the total size of the Icelandic Oystercatcher population, based on a recent estimate of 13 thousand breeding pairs (Skarphéðinsson et al. 2016) . How many sub-adults are there to add to the 26,000 breeding birds?

In order to estimate the proportion of migrants and residents it was necessary first to determine the total size of the Icelandic Oystercatcher population, based on a recent estimate of 13 thousand breeding pairs (Skarphéðinsson et al. 2016) . How many sub-adults are there to add to the 26,000 breeding birds?

Verónica Méndez and her team have shown that Oystercatchers fledge on average about 0.5 chicks per pair. Using estimates that 50% of these chicks are alive by mid-winter, that there is then a 90% chance of annual survival and birds typically breed when they are four years old, it was possible to come up with a total population of just over 37,000 birds.

Although the authors of the paper have produced the best winter estimate thus far, they note that it is a minimum – there could be small numbers of birds in other areas. At 11,141 out of 37,177 birds, the minimum estimate of the residential part of the population is 30%, leaving 70% to be distributed around the coasts of the British Isles and (in smaller numbers) along the coastline of mainland Europe.

Latitudinal expectation

To put the migratory status of the Icelandic Oystercatcher into context with other Oystercatcher populations breeding in NW Europe, the authors collated information about the proportion of resident and migratory Oystercatchers in coastal countries between Norway and the Netherlands. They show that there is a strong latitudinal decline in residency. From Northern Norway (69.6°N) to Southern Sweden (57.7°N), where mean January temperatures are typically in the range of -1 to -4°C, only occasional individuals are found in winter, whereas populations in Denmark (55.4°N), where mean January temperatures 0.8°C, and sites that are further south and warmer mostly comprise resident individuals.

To put the migratory status of the Icelandic Oystercatcher into context with other Oystercatcher populations breeding in NW Europe, the authors collated information about the proportion of resident and migratory Oystercatchers in coastal countries between Norway and the Netherlands. They show that there is a strong latitudinal decline in residency. From Northern Norway (69.6°N) to Southern Sweden (57.7°N), where mean January temperatures are typically in the range of -1 to -4°C, only occasional individuals are found in winter, whereas populations in Denmark (55.4°N), where mean January temperatures 0.8°C, and sites that are further south and warmer mostly comprise resident individuals.

This cline in migratory tendency is also seen within the British Isles, which stretch from 60.8°N to 50.2°N. Writing in the BTO’s Migration Atlas, Humphrey Sitters reports that birds from the north of the British Isles have a median recovery distance of 213.5 km, whereas in the west, east, south and Ireland the respective figures are 35.5, 27.0, 6.0 and 13.5 km. In each group, there are birds that travel over 800 km, implying some degree of migratory tendency in birds breeding in every part of the British Isles.

This cline in migratory tendency is also seen within the British Isles, which stretch from 60.8°N to 50.2°N. Writing in the BTO’s Migration Atlas, Humphrey Sitters reports that birds from the north of the British Isles have a median recovery distance of 213.5 km, whereas in the west, east, south and Ireland the respective figures are 35.5, 27.0, 6.0 and 13.5 km. In each group, there are birds that travel over 800 km, implying some degree of migratory tendency in birds breeding in every part of the British Isles.

Iceland lies between 63.2°N and 66.3°N, which puts it well within the latitudinal range of the ‘almost-all-migrate’ group of Scandinavian birds. The Icelandic proportion of 30% residency is likely to be a function of the temperature and geographical isolation of the island. Bathed by the relatively warm waters of the Gulf Stream, some coastal areas, particularly in the west of Iceland, provide a relatively mild oceanic climate and apparently ample food stocks to support high survival during most winters. On the other hand, days are very short. For an Oystercatcher that spends December in Reykjavik, the time between sunrise and sunset is just four hours and the average January temperature is -0.6°C. For a bird in Dublin day-length figure is almost twice as long, at seven and a half hours, and temperature is 5.3°C. Food availability may well be compromised by the time available to collect it, as previous studies have shown that feeding efficiency is on average lower at night.

Iceland might hold a higher proportion of residents than would otherwise be the case as it is far enough away from Britain (about 750 km to mainland Scotland) and Ireland for the sea crossing to potentially be a significant barrier. For migrants, time will need to be spent acquiring the reserves needed for the journey south in the autumn and north in the spring and the flights may well add costs in terms of survival probability.

Iceland might hold a higher proportion of residents than would otherwise be the case as it is far enough away from Britain (about 750 km to mainland Scotland) and Ireland for the sea crossing to potentially be a significant barrier. For migrants, time will need to be spent acquiring the reserves needed for the journey south in the autumn and north in the spring and the flights may well add costs in terms of survival probability.

There is a blog about the broader project to understand how individual birds become ‘programmed’ to be migrants or residents here: Migratory decisions for Icelandic Oystercatchers.

The migration option

If 30% of Oystercatchers are staying in Iceland this implies that up to 26,000 birds of Icelandic origin are to be found in the British Isles and on the western coast of Europe during the winter. Some of these – young birds that are yet to breed – can be found in these areas in the summer too. By the end of the summer of 2017, Verónica Méndez and her team had colour-ringed about 800 (500 adults, 300 juvenile) birds in Iceland, in order to try better to understand the reasons for the migratory/residency decisions that individuals make. Every dot on the map alongside (which was created on 1st June 2018) represents a migratory bird. Each record is valuable and there are lots more birds to try to find! Are there really no Icelandic Oystercatchers in the vast flocks of eastern England?

If 30% of Oystercatchers are staying in Iceland this implies that up to 26,000 birds of Icelandic origin are to be found in the British Isles and on the western coast of Europe during the winter. Some of these – young birds that are yet to breed – can be found in these areas in the summer too. By the end of the summer of 2017, Verónica Méndez and her team had colour-ringed about 800 (500 adults, 300 juvenile) birds in Iceland, in order to try better to understand the reasons for the migratory/residency decisions that individuals make. Every dot on the map alongside (which was created on 1st June 2018) represents a migratory bird. Each record is valuable and there are lots more birds to try to find! Are there really no Icelandic Oystercatchers in the vast flocks of eastern England?

If you come across a colour-marked Oystercatcher, please report it to icelandwader@gmail.com

Graham (@grahamfappleton) has studied waders for over 40 years and is currently involved in wader research in the UK and in Iceland. He was Director of Communications at The British Trust for Ornithology until 2013 and is now a freelance writer and broadcaster.

Great to see so many oysters.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: WaderTales blogs in 2018 | wadertales

Pingback: Fennoscandian wader factory | wadertales

Pingback: Which Icelandic Oystercatchers cross the Atlantic? | wadertales

Pingback: Spot the oystercatcher: One of the best known birds in Iceland

Pingback: Migration of Scottish Greenshank | wadertales

Pingback: Sjáðu tjaldinn: Einn þekktasti fugl landsins | Perlan Museum

Pingback: Oystercatcher Migration: the Dad Effect | wadertales

Pingback: When mates behave differently | wadertales