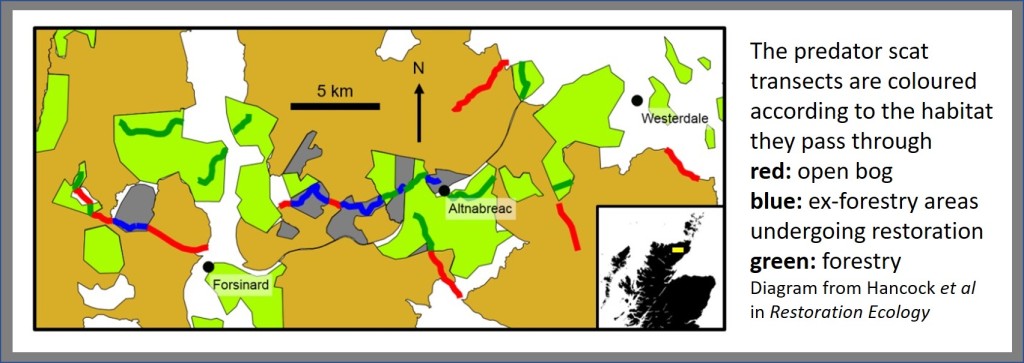

When trees are planted in open habitats that support breeding waders, numbers usually decline pretty quickly. Trees not only directly remove once-occupied habitat, they are also thought to attract predators, by providing somewhere to hide. In their paper in Restoration Ecology, Mark Hancock and colleagues investigate the distribution of thousands of scats of mammalian predators, in order to understand predator activity in landscapes associated with open bogs and forest edge. They were particularly interested in seeing how long it takes for predators to move out of an area when trees are removed and the land once more reverts to blanket bog.

This study took place alongside a project to repair damage to the vast Flow Country blanket bog (northern Scotland), that occurred in the 1980s, when non-native conifer trees were planted in areas of deep peat that had been drained and deep-ploughed. Such forestry practises would nowadays be prohibited.

More trees

The spread of trees can occur naturally, as the northern treeline moves further north or as trees grow higher in mountain regions, or it can be imposed or accelerated when trees are planted in previously open environments. Warmer temperatures create more opportunities for afforestation and politicians seem to be responding to rising CO2 levels by opting for what seems like an easy win – ‘let’s plant more trees’. In the right places, using appropriate native species, woodland can help to capture carbon**, support woodland wildlife and provide multiple other benefits to society. However, if afforestation focuses on open wet landscapes it can potentially threaten ground-nesting wader species such as Dunlin and Curlew.

** link to The value of habitats of conservation importance to climate change mitigation in the UK by Rob Field and colleagues in Biological Conservation.

As Mark Hancock and colleagues indicate in the abstract of their paper, afforestation of formerly open landscapes can potentially influence mammalian predator communities, with impacts on prey species like ground-nesting birds. In Scotland’s Flow Country, a globally important peatland containing many forestry plantations, earlier studies found reduced densities of breeding waders on open bogs where forestry plantations were present within 700 m. See Hancock et al. 2009 and Wilson et al. 2014. A previous WaderTales blog discussed whether apparent avoidance is due to actual or perceived predation risk (See Mastering Lapwing conservation) but whichever it is, adding new woodland to open wetland habitats has the potential to affect sensitive breeding waders.

There have been many studies looking at the effects of trees on breeding waders but the key differences in this case were that researchers monitored how mammal distributions changed as woodland was removed, in an effort to restore biodiversity and valuable blanket-bog habitats. Spoiler alert: it takes several years to reduce predator numbers!

By counting scats of species as diverse as fox and hedgehog the team were able to address three questions:

- Did scat distributions vary between open bog, forestry plantations, and former plantations being restored as bog (‘restoration’ habitats)?

- How fast did scat numbers change in restoration habitats?

- Were scat numbers different in bogs with differing amounts of nearby forestry?

Counting the poo

The analyses in this paper are based upon surveying 819 km of track verges, which yielded a total of 2806 scat groups (groups of scats that could have come from one animal) from a variety of predators. I smile when days and days of painstaking fieldwork are summarised in a sentence. “We measured summer scat density and size over 14 years, in 26 transects 0.6-4.5 km in length, collecting data during 93, 96 and 79 transect-years in bog, forestry and restoration habitats respectively”. There is no mention of midges either!

The Flow Country is host to a range of predatory mammals. Hedgehog, Wildcat, Red Fox, Badger, Pine Marten, Stoat and Weasel are native species, while introduced species like Feral Ferret and American Mink may be threatening the area. A 10 mm diameter scat could have been produced by one of six or more species – and increasingly it has been shown that genetic methods, which were outside the budget of this study, are needed to properly identify species from a scat. As all of these species prey on the eggs and/or chicks of breeding waders, the study treated them as a ‘guild’ of animals having similar potential effects.

In April each year, fieldworkers – many of them volunteers based at RSPB’s Forsinard Flows reserve – walked along each of the transects, removing all of the scats from the tracks and track-edges. In July, scats and scat groups that had been deposited on the tracks during the breeding season were counted, measured and their positions recorded using GPS (see paper for details).

Nine transects were in open bog habitat, that remained broadly unchanged throughout the study, 8 were in forestry plantations, 8 were in forestry plantations that were cleared and then restored during the study and 1 site was already a restored plot. For ‘restoration’ transects, the number of years since felling was used as a measure of the length of time under restoration management. In these restoration areas, the brash that was left after felling gradually rotted away or became buried by recovering bog vegetation as re-wetting management (e.g. drain blocking) took effect.

Where’s the poo?

Predator activity in different habitats and over time. For bog and restoration habitats, scat group density was relatively low throughout the study, averaging around 1 to 2 scat groups per km. In forestry transects, scat group densities started at similar values, but rose approximately eight-fold over the study period, as the forests matured. In the final year of the study, scat group densities in forestry averaged around eight groups per km – approximately twice the figures in restoration and six times the figure in bog habitats. There is a suggestion that more mature forests may have suited Pine Martens, in particular: this species was recorded in the heart of the Flow Country for the first time during the study period.

Predator activity once trees are removed. Scat group density differed significantly between restoration areas of different age classes. In recently-felled sites (1-5 years), densities were about 2.4 groups per km, rising to 4.0 in the middle period (6-10) and falling to 1.3 later (11-14 years). The authors suggest that tree removal may lead to a flush of nutrients, grasses and then small mammals, thereby explaining the increase in scat densities during the middle stage (6-10 years). The paper demonstrates that it takes several years for mammal densities to fall back to ‘natural’ levels, after tree removal.

Predator activity close to forests. Scat density on open bog transects was significantly affected by the presence of at least 10% forestry cover within 700 m. There was an estimated 2.9 times (95% confidence limits 1.4 to 6.0) higher scat density at bog transects which contained over 10% cover of forestry within 700 m, compared to bog transects with less forestry nearby. Scottish studies of breeding waders have shown that species such as Golden Plover, Dunlin and Curlew avoid areas close to forestry and the paper includes references to several other similar studies elsewhere.

The Conservation picture

As pointed out by Hancock et al in their Discussion, scat densities in forestry reached much higher values than those of open bogs, especially as the plantations matured, implying that afforestation had strongly altered patterns of mammalian predator occurrence in this formerly open landscape. It took ten years of restoration management to drive down scat densities to levels similar to those of open bogs but, as the authors note, peatland restoration is a rapidly developing field and newer techniques may allow faster restoration, with both biodiversity and soil carbon benefits.

These findings have implications way beyond the scope of this study, three examples of which are included below:

Commercial forestry is seen by some as a way of capturing carbon and can provide opportunities to restore our woodlands, especially our native woodlands and their associated biodiversity. However, given the vulnerability of ground-nesting birds to predation, and the potential for afforestation to markedly affect predator communities, care needs to be exercised when considering afforestation of open landscapes.

Warmer climates offer opportunities to add forestry to the mix of land use options in areas in which the growing season used to be considered too short. For instance, there is significant development pressure in Iceland to plant large areas of non-native commercial forestry. Given that the country holds half or more of Europe’s breeding Whimbrel, Dunlin and Golden Plover this is a contentious issue. This AEWA report is important: Possible impact of Icelandic forestry policy on migratory waterbirds.

In Ireland, it has been suggested that a patchy distribution of relatively new forestry plantations may be one of the factors contributing to the drastic decline of Curlew numbers. (Ireland’s Curlew crisis describes a 96% decline in just 30 years). It has been proposed that some of these patches should be removed. The Hancock et al paper shows how long it might take to make a difference – ten years may simply be too long for Ireland’s breeding Curlew.

Read more

The paper that forms the basis of this blog is:

Guild-level responses by mammalian predators to afforestation and subsequent restoration in a formerly treeless peatland landscape by Mark H. Hancock, Daniela Klein and Neil R. Cowie. Published in Restoration Ecology. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/rec.13167

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton, to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on previously published papers, with the aim of making wader science available to a broader audience.

Reblogged this on Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: Trees should not be planted in peatlands (such as blanket bog, wet heath, mires) | henryadamsblog

Pingback: WaderTales blogs in 2020 | wadertales

Pingback: On the edge: curlews suffering from conifer plantations in Northern Ireland and beyond – Curlew Action

Pingback: Remote monitoring of wader habitats | wadertales

Pingback: On the edge: curlews suffering from conifer plantations in Northern Ireland and beyond – Curlew Action

Pingback: Keep away from the trees | wadertales

Pingback: Iceland’s waders need a strategic forestry plan | wadertales

Pingback: The Curlew Trial Management Project - Saving Nature With Science - Our work - The RSPB Community