The Grey Plover may be grey in the winter but in its summer plumage the American name of Black-bellied Plover is far more appropriate. Each spring, adults moult into this breeding finery but what happens to first-years, are there differences between the sexes and are Grey Plovers ‘typical’ of the wader family as a whole?

The Grey Plover may be grey in the winter but in its summer plumage the American name of Black-bellied Plover is far more appropriate. Each spring, adults moult into this breeding finery but what happens to first-years, are there differences between the sexes and are Grey Plovers ‘typical’ of the wader family as a whole?

This blog is inspired by the moult chapter from Shorebirds in Action, a book by Richard Chandler, published by Whittles Publishing. The descriptor “an introduction to waders and their behaviour” gives a clue to the fact that Richard has used his excellent photographs to illustrate aspects of shorebirds’ lives, such as moult, migration, territorial behaviour and physiology. Many of the photographs in this blog have been provided by Richard.

‘Dressing for the Occasion’

Back in the ‘old days’ a group of wader ringers would huddle over the outstretched wing of a shorebird, often in the dark, by the light of a paraffin lamp, in order to try to understand the moult of individual birds. In the case of the Grey (or Black-bellied) Plover, the primary feathers sometimes revealed an interesting story of previous difficulties experienced by an individual. More of this later.

Thanks to the development of digital photography and long lenses, the study of moult is no longer restricted to ringers looking at birds in the hand. Birdwatchers can all share in the detective work and learn more about how plumages of waders change with age and season, allowing us to identify males and females and to think about the stresses that individuals face.

The moult of Grey Plovers

Most waders moult their main flight feathers in the autumn and take on summer plumage in the spring. This adult Grey Plover (below) was photographed on the Wash in Norfolk in August. It is not in full summer plumage, having started its moult before migrating from the Taymyr region of Siberia. There’s lots more about wader migration here. Two of the primaries (P1 and P2) are new, with crisp white edges to the feathers. Over the course of the next few weeks, this bird will recommence moult by dropping P3, with moult then progressing outwards through the primaries and inwards through the secondaries. The main feather tracts are labelled.

Summer plumage feathers can be seen in the scapulars and in the coverts. In some individual Grey Plovers, and in other species, there can also be summer plumage in the tertials. In this photograph, these are hidden by the large, showy scapulars. Juvenile birds of many species are often aged by looking for buffy tips on the median coverts. The inner median coverts are protected from wear by the scapulars, so this is the best place to look for hidden evidence that a bird is a youngster. This is where to find the odd buffy fringe in a young Dunlin in its first spring, for instance, when it is about 10 months old.

For an adult wader, the post-breeding moult is complete. The photograph alongside shows an adult bird in full winter-plumage; the picture is from Norfolk (UK) but the same photograph could have been taken in South Africa, India, Australia or South America, so global is the Grey Plover’s distribution. The bird has discarded all of the breeding plumage it acquired in the spring, and the flight feathers that were a year old. All of the coverts of the wing have been moulted and have a uniform appearance, and look at the fresh-edged tertials that fold neatly over the dark (almost black) tips of the primaries.

For an adult wader, the post-breeding moult is complete. The photograph alongside shows an adult bird in full winter-plumage; the picture is from Norfolk (UK) but the same photograph could have been taken in South Africa, India, Australia or South America, so global is the Grey Plover’s distribution. The bird has discarded all of the breeding plumage it acquired in the spring, and the flight feathers that were a year old. All of the coverts of the wing have been moulted and have a uniform appearance, and look at the fresh-edged tertials that fold neatly over the dark (almost black) tips of the primaries.

The next photograph shows a first-winter juvenile, newly arrived from the breeding grounds. This bird is a Black-bellied Plover in Florida. Having started life as a tiny, downy chick, it will have acquired this new set of feathers before migration. The spangling of the back is diagnostic of a juvenile Grey Plover but the golden spots can confuse a novice wader-handler, who might want to turn it into one of the golden plover family. Before winter starts, new non-breeding-type body feathers moult in, so the bird loses the spangling of the upper parts and a lot of the streaking of the under-parts.

The next photograph shows a first-winter juvenile, newly arrived from the breeding grounds. This bird is a Black-bellied Plover in Florida. Having started life as a tiny, downy chick, it will have acquired this new set of feathers before migration. The spangling of the back is diagnostic of a juvenile Grey Plover but the golden spots can confuse a novice wader-handler, who might want to turn it into one of the golden plover family. Before winter starts, new non-breeding-type body feathers moult in, so the bird loses the spangling of the upper parts and a lot of the streaking of the under-parts.

It is not thought that one-year-old Grey Plovers breed in their first summer, with most staying on their ‘wintering’ grounds for well over a year, through to the second April or May. The photograph alongside was taken in May in Norfolk; the bird may have been sharing the beach with gorgeous summer-plumage birds that were preparing to depart for Siberia. Grey (or Black-Bellied) Plovers are nearly circumpolar breeders. They are missing from Greenland and Northern Scandinavia but breed across the northern coasts of Russia, Alaska and Canada – only three countries but a vast area of tundra.

It is not thought that one-year-old Grey Plovers breed in their first summer, with most staying on their ‘wintering’ grounds for well over a year, through to the second April or May. The photograph alongside was taken in May in Norfolk; the bird may have been sharing the beach with gorgeous summer-plumage birds that were preparing to depart for Siberia. Grey (or Black-Bellied) Plovers are nearly circumpolar breeders. They are missing from Greenland and Northern Scandinavia but breed across the northern coasts of Russia, Alaska and Canada – only three countries but a vast area of tundra.

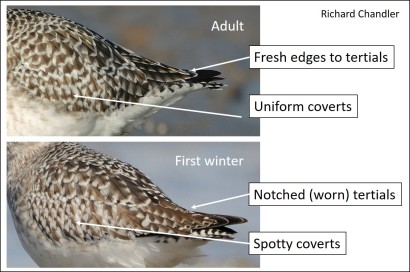

The next figure is a composite of two of the photographs, created to show the key diagnostic features of an adult and immature in winter plumage. The notches on the tertials are particularly pronounced in the young bird because the feathers were already nearly a year old at this point – it is not always this easy! When assessing the age of any wader, the tertials and coverts are key feathers to check out.

The next figure is a composite of two of the photographs, created to show the key diagnostic features of an adult and immature in winter plumage. The notches on the tertials are particularly pronounced in the young bird because the feathers were already nearly a year old at this point – it is not always this easy! When assessing the age of any wader, the tertials and coverts are key feathers to check out.

Primary exceptions

In many ways, the Grey Plover is a fairly typical medium-sized wader; adults moult their main flight feathers (wings and tail) in the autumn but juveniles have to wait until the early summer of their second year before they do the same. This first primary moult of these young birds may start as early as June and is completed in August or early September, two months ahead of breeding adults. To learn more about Grey Plover moult see this paper by Nick Branson & Clive Minton from the Wash Wader Ringing Group.

Smaller waders, such as the alpina Dunlin that spend the winter in Britain & Ireland, typically breed when only a year old. Unlike Grey Plovers, Dunlin moult into breeding plumage in their first spring. When they return from Russia in the same summer they can still be aged if there are juvenile inner median coverts with unworn buffy fringes. Primaries in these one-year-old birds tend to be more worn than those of adults, being three months older and having been used for one more migratory journey.

In some species, such as Semipalmated Sandpiper, you can find young birds in the spring with a small number of fresh outer primaries. By moulting the outer, and most worn, of their flight feathers during the wintering period they are presumably able to increase flight efficiency for the journeys north and south. Young birds of the tundrae race of the Ringed Plover take this early primary renewal strategy even further, by undergoing a complete primary moult in their first winter, while on the wintering grounds.

Under stress

Moult is an energetically expensive activity. When resources are low, it may not be possible to complete the moult process. In this BTO report by Phil Atkinson and colleagues, about wader mortality associated with die-offs of cockles and mussels in the Wash (UK), they showed that more Oystercatchers suspend moult in years with very low food supplies. In these ‘bad shellfish years’, it was not uncommon to find Oystercatchers with one or more unmoulted outer primaries – old feathers that would be retained until the next autumn moult.

The same thing can happen in Grey Plovers but it is more likely that they will suspend moult in the autumn and then finish in March. In the Branson & Minton paper mentioned above, it was estimated that 30% of adults suspended moult for the harsh winter months. The paper was written in 1976 and it would be interesting to know whether the proportion of birds suspending has dropped, given that winter weather now tends to be less severe.

The same thing can happen in Grey Plovers but it is more likely that they will suspend moult in the autumn and then finish in March. In the Branson & Minton paper mentioned above, it was estimated that 30% of adults suspended moult for the harsh winter months. The paper was written in 1976 and it would be interesting to know whether the proportion of birds suspending has dropped, given that winter weather now tends to be less severe.

Suspended moult is found in Grey and Black-bellied Plovers across the world. The photograph alongside was taken in Florida on 20 December. The unmoulted outer primary is more pointed and browner than the other nine.

Gender

The gender of winter-plumage Grey Plovers cannot be determined, even in the hand, but the summer plumage is pretty diagnostic. A bird with a jet-black belly, with perhaps the odd white tip to a feather, and an almost pure white band behind the black face and neck is probably a male (as here). If the bird is less well-marked – brownish-black on the front with more mottling – then you are likely to be looking at a breeding plumage female. Come the autumn, all of this finery will disappear and the Black-bellied Plover will become a Grey Plover once more.

The gender of winter-plumage Grey Plovers cannot be determined, even in the hand, but the summer plumage is pretty diagnostic. A bird with a jet-black belly, with perhaps the odd white tip to a feather, and an almost pure white band behind the black face and neck is probably a male (as here). If the bird is less well-marked – brownish-black on the front with more mottling – then you are likely to be looking at a breeding plumage female. Come the autumn, all of this finery will disappear and the Black-bellied Plover will become a Grey Plover once more.

Moult in other species

This blog focuses on the moult of one species. If you want to learn more about moult in general and many other aspects of the behaviour of waders then immerse yourself in Shorebirds in Action, An Introduction to Waders and their Behaviour by Richard Chandler. Click here for link.

This blog focuses on the moult of one species. If you want to learn more about moult in general and many other aspects of the behaviour of waders then immerse yourself in Shorebirds in Action, An Introduction to Waders and their Behaviour by Richard Chandler. Click here for link.

Moult features strongly in this WaderTales blog about Black-tailed Godwits and in this blog about Lapwings.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton, to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on previously published papers, with the aim of making wader science available to a broader audience.

Reblogged this on Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: Wetland Bird Survey: working for waders | wadertales

Pingback: WaderTales: a taste of Scotland | wadertales

Pingback: WaderTales blogs in 2017 | wadertales

Pingback: Starting moult early | wadertales

Pingback: Sixty years of Wash waders | wadertales

Pingback: The First Five Years | wadertales

Excited to see a black bellied plover wading on the edge of an incoming tide in the harbour at Lindisfarne, Holy Island, Friday 7 May 2022. Have a photo but from just over 100 m. Never seen a black bellied plover before. Very exciting! Anne Hunt

LikeLike

Yes. Stunning in May. One of the last waders to head north. More here: https://wadertales.wordpress.com/2020/06/11/plovers-from-the-north/

LikeLike