In a paper in the BTO journal, Ringing & Migration, Ken Smith and his collaborators review how wearing a tag, attached using a harness, affects the preening and feeding behaviour of Green Sandpipers. What did they find and where do their Hertfordshire birds spend the summer?

The lives of Green Sandpipers

According to BirdLife International’s Data Zone page, there are between 1.2 million and 3.6 million Green Sandpipers across Europe and Asia. The breadth of this estimate reflects the difficulty of assessing the population of a species that breeds in wet forest clearings, from western Norway to about 155 degrees east in Russia. It’s hardly any easier to count them in the winter, sprinkled as there are around small pools, in ditches and along river valleys from West Africa to Japan.

According to BirdLife International’s Data Zone page, there are between 1.2 million and 3.6 million Green Sandpipers across Europe and Asia. The breadth of this estimate reflects the difficulty of assessing the population of a species that breeds in wet forest clearings, from western Norway to about 155 degrees east in Russia. It’s hardly any easier to count them in the winter, sprinkled as there are around small pools, in ditches and along river valleys from West Africa to Japan.

The occasional pair of Green Sandpipers breed in the UK and Population Estimates of Birds in Great Britain and the United Kingdom, published in British Birds by Andy Musgrove at al suggests, that fewer than 1000 birds spend the winter here, although rather more are seen on passage between Scandinavia and Africa. In an ever-changing world, studying populations of a species that is at the edge of its range has the potential to explain patterns of loss (or gain) that are less obvious in the heart of a species’ distribution.

Why use geolocators?

In a previous blog (Bar-tailed Godwits: migration & survival), it was shown that colour-rings, which enable individual recognition of a bird without capture, provided 30 times as much information about annual survival as a metal ring. Adding a geolocator takes you into a new data-rich environment. A geolocator is a small device that records the location of an animal. By recapturing a bird a year after ringing and downloading these data, important information about the timing of migration, the duration of stop-overs at fuelling sites and the exact breeding and/or wintering location can be ascertained.

One of the important things to appreciate about scientists who study bird migration is that they are as keen as any other birdwatcher to ensure that the tracking devices they use cause as little disturbance to the normal life of their study birds as possible.

Attaching geolocators

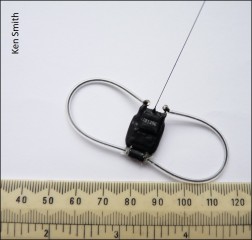

Geolocator with a light-stalk

In shorebird research, the most common form of geolocator is one that is attached to a ring on the bird’s leg. For most individuals, these devices do not have any negative effects but for smaller waders there can be some problems. Shorebird ecologists from around the globe cooperated to review these issues , publishing it in Movement Ecology. It is summarised in the WaderTales blog, Are there costs to wearing a geolocator? Hopefully, anyone contemplating a new shorebird study will read these before starting. Any data that are collected are only valuable if the birds are either unaffected by the equipment and attachment methods or, if there are effects, these do not prejudice the scientific integrity of the study or the welfare of the birds.

GPS geolocator, fitted with elastic loops to form the harness

In this study, the Green Sandpipers were fitted with leg loop harnesses, first described by Rappole and Tipton, the authors having decided that ring-mounted geolocators might be too bulky on such a small wader. These harnesses are looped around the top part of a bird’s legs so that the geolocator sits like a small rucsac on the lower back, nestled in the feathers. In the figure below, the left picture shows a tagged bird; you may just make out a slight lifting of the back feathers over the top of the geolocator light stalk. The right-hand picture has been annotated to show how the ‘rucsac’ is fitted.

The geolocators and harnesses represented 1.4–1.6% of the body mass of the birds. In the study, two different types of device were used, light-level geolocators and GPS geolocators – see the details in the paper. The effects of tagging on behaviour patterns have been examined and written up as a paper in the BTO journal Ringing & Migration, using data collected from seven Green Sandpipers that were fitted with harnesses.

Feeding and preening behaviour

Ken Smith and his colleagues have been studying the Green Sandpipers wintering at Lemsford Springs Nature Reserve in Hertfordshire, southeast England for over thirty years. These shallow lagoons were previously managed as watercress beds. In this particular investigation, the scientists compared the behaviour patterns of individual birds fitted with geolocators, before and after tagging, with a control group of untagged birds. They were particularly interested in the proportion of time spent feeding and preening. Feeding time was thought to be an indication of normal foraging behaviour and preening would be an indication of any discomfort or unfamiliarity caused by the tags and harnesses.

Green Sandpipers spend their time feeding, preening and roosting, with most of the feeding activity occurring in loosely defined territories. Four of the tagged birds could be viewed regularly and their activities were observed alongside seven untagged (but colour-ringed) individuals. The amount of time spent feeding increased as days lengthened in the spring and birds prepared for migration. Previous research has shown that the Green Sandpipers on this site are not constrained by feeding opportunities, except in the coldest of condition. In these latter circumstances birds will also feed at night but normally they only feed during the day.

Investigating tag effects

Lemsford is a well-watched site. Most birdwatchers couldn’t tell which birds were tagged and which ones were not. The tags were so well preened into the plumage that they were extremely difficult to see, even in high-quality photographs. The tags could only be spotted by experienced observers and tag-effects could only be established using 20,000 minutes of observations. A less-intensive study would have showed no significant effects. These bullet points summarise more detailed findings in the paper:

Lemsford is a well-watched site. Most birdwatchers couldn’t tell which birds were tagged and which ones were not. The tags were so well preened into the plumage that they were extremely difficult to see, even in high-quality photographs. The tags could only be spotted by experienced observers and tag-effects could only be established using 20,000 minutes of observations. A less-intensive study would have showed no significant effects. These bullet points summarise more detailed findings in the paper:

- All four tagged birds that were closely observed in this study returned successfully from their breeding areas and three of the tags were retrieved. There were no apparent signs of any problems such as skin abrasion or feather wear, caused by the tags or harnesses, and the birds continued to be observed after their tags were removed. The one bird that evaded capture and whose tag was not retrieved was present throughout the second winter.

- Within the wider group, eight out of ten birds with tags returned the next winter, which is not significantly different from the overall return rate for untagged birds.

- Tagged birds spent a small but significantly higher percentage of their time preening than untagged birds (untagged birds 4.6%, tagged birds 6.3%). Comparing the periods immediately before and after tagging for the four tagged birds for which detailed observations were collected, there were no differences in the time spent feeding but a significantly higher proportion of the time was spent preening (rather than just resting).

- Birds may well get used to their tags over time. Of the three tagged birds for which there was sufficient data, two showed significant declines in the proportion of time spent preening over time (15% down to 5%), whereas one was at 6% throughout.

Where do these Green Sandpipers go?

Colour-ringing at Lemsford had already shown that birds are very site-faithful during the winter, once autumn passage birds have moved through. There’s more about this in a previous paper in Bird Study: Habitat use and site fidelity of Green Sandpipers Tringa ochropus wintering in southern England.

Addition in 2021. Lemsford is a passage site as well as a wintering site, with some colour-ringed birds travelling further south to Spain and Portugal. A bird ringed at Lemsford in July 2018, as a juvenile, spent seven weeks on site in the summer of 2020 and turned up again in 2021. It was last seen at 1600 on 23rd August and then photographed in Spain the next day, just 26.5 hours later and nearly 1000 km further south. There is a blog about this in Spanish/English.

This map was downloaded from the BTO website in 2021

At the time that the Migration Atlas (Movements of the Birds of Britain & Ireland) was written, using data collected between 1909 and 1997, there was only one record of a BTO-ringed bird in its breeding area. That bird was found in Sweden, and there has been one other in Finland since. Green Sandpipers are not easy birds to observe and, although the long-term colour-ringing project at Lemsford Springs has generated large numbers of local re-sightings, there have been none elsewhere.

Addition in 2024. In a paper in Bird Study in 2024, the Smith, Trevis and Reed team revealed the breeding locations of nine Lemsford birds: one in Finland, three in Norway, four in Sweden and one on the Norwegian/Swedish border. Tracking detected two direct migrations of about 24 hours in the spring, with less urgency to fly south in June/July. The shortest stay in the breeding area was only 27 days and the longest was 72 days. As in most waders, females headed south earlier than males.

There is a WaderTales blog that summarises migration of over 40 wader species to, from and through Britain & Ireland: Which wader, when and why?

This paper

Although this study has involved small numbers of tagged and untagged birds, it has shown a consistent pattern of increase in the proportion of time spent preening by birds after tagging, with some evidence that this subsequently decreases over time. There is no evidence of an adverse impact on return rates of tagged birds from one winter to the next, although with such small sample sizes only a major change would have been detectable.

Although this study has involved small numbers of tagged and untagged birds, it has shown a consistent pattern of increase in the proportion of time spent preening by birds after tagging, with some evidence that this subsequently decreases over time. There is no evidence of an adverse impact on return rates of tagged birds from one winter to the next, although with such small sample sizes only a major change would have been detectable.

This paper is published in the BTO journal, Ringing & Migration:

*** IMPORTANT ADDITION ***

There is more GUIDANCE about the use of TAGS and FLAGS in a later blog about Common Sandpipers: Flagging up potential problems.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton, to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on previously published papers, with the aim of making wader science available to a broader audience.

I’m glad that the tags don’t seem to bother them much. Good to get the data to study.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Which wader, when and why? | wadertales

Pingback: Are there costs to wearing a geolocator? | wadertales

Pingback: Leg-flags and nest success | wadertales

Pingback: WaderTales blogs in 2018 | wadertales

Pingback: Winter territories of Green Sandpipers | wadertales

Pingback: Not-so-Common Sandpipers | wadertales

Pingback: Whimbrel: time to leave | wadertales

Pingback: Migration blogs on WaderTales | wadertales

Pingback: Migration of Scottish Greenshank | wadertales

Pingback: Flagging up potential problems | wadertales

Pingback: WaderTales wins BTO Award | wadertales

Pingback: Dunlin: tales from the Baltic | wadertales