In a rapidly changing world, wintering waders face unprecedented challenges. How much flexibility is there for individuals to cope with issues such as over-fishing of shellfish stocks, habitat removal, pollution, and the effects of rapid climate warming on their food supplies?

Colour-ring records show that many wintering waders tend to be site-faithful, feeding in the same estuaries and even the same small patches year after year. This makes sense if food supplies are reliable and predictable but what happens when there is massive change in food abundance? In a 2021 paper in MEPS, Katharine Bowgen and co-authors describe the impacts of a cockle die-off in the Burry Inlet (part of the Severn Estuary in Wales) on the local population of Eurasian Oystercatchers. Their findings illustrate how important it is to protect networks of sites, rather than individual inlets or estuaries.

Assessing the options

When food supplies are low – or crash suddenly – what can birds such as Oystercatchers do? There are three likely options in these circumstances:

- Wait and hope

- Move elsewhere and never return

- Move elsewhere until conditions improve

If ‘wait and hope’ is the main option then, following an event that reduces food availability or abundance, there should be little evidence of birds dispersing, measures of annual survival might be depressed for a period and, once conditions improve in the area, young birds might be likely to fill the spaces available. This should lead to higher proportions of sub-adults in the period immediately after such a hiatus and a steady increase in numbers.

Movements to other sites, whether temporary or permanent ought to be detectable from mid-winter counts and through reports of ringed birds. The pattern after a permanent shift in birds would be similar to that following mortality; again, young birds might be expected to take advantage of food resources as they recover In reality, of course, individual birds that use a site may opt for any one of the three options, creating a mixed picture.

Oystercatcher numbers

Over recent decades, numbers of Eurasian Oystercatchers have declined. In 2015 the species was reclassified as “Near Threatened” on the IUCN’s Red List (Birdlife International) and “Vulnerable” within Europe. It is also Amber listed on the UK’s Birds of Conservation Concern list, due to its European status, the concentration of its wintering population in protected sites and the international importance of UK breeding and wintering populations.

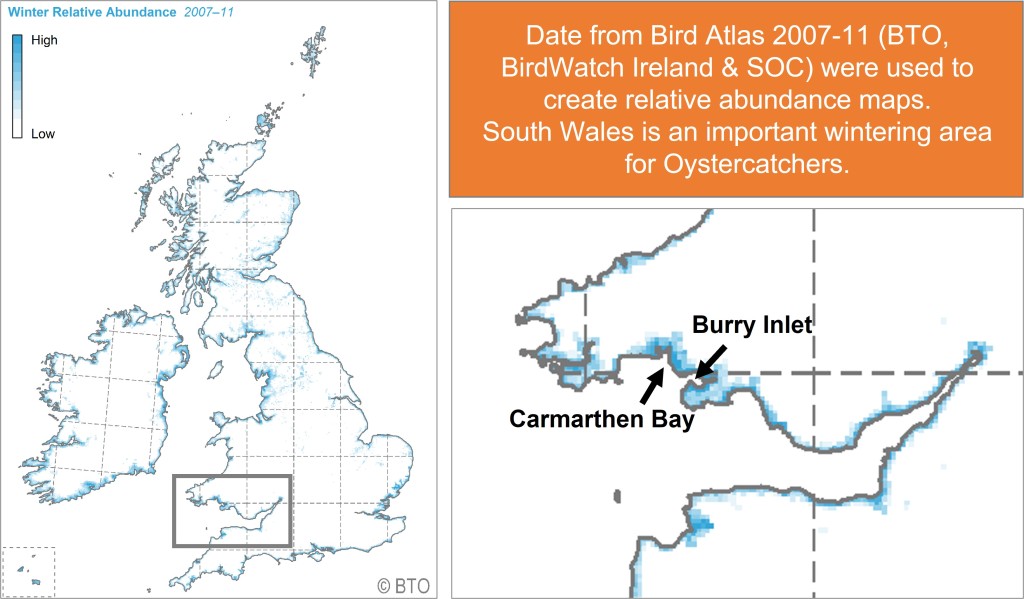

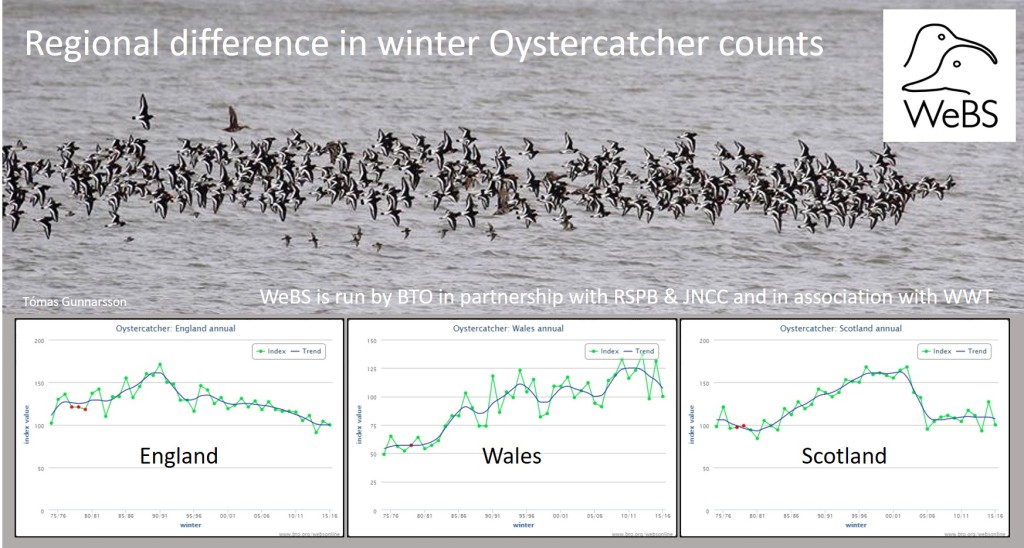

The changes in Burry Inlet Oystercatcher numbers should be viewed within a pattern of national declines. Since the 1990s, winter numbers on UK estuaries have dropped by a third, back to levels seen in the 1970s. Patterns around Great Britain vary (see below); Welsh numbers on estuaries, as assessed by WeBS, have held up well but there has been a 25-year period of decline in England and there was a sudden fall in Scottish numbers at the start of this century.

The Burry Inlet

The intertidal mudflats of the Burry Inlet in south Wales are of international importance for non-breeding waterbirds of various species, including the Eurasian Oystercatcher. This SPA (Special Protection Area) is part of The Carmarthen Bay and Estuaries SAC (Special Area of Conservation). Burry Inlet received significant conservation attention back in the 1970s, when the UK government gave permission for 10,000 Oystercatchers to be shot, to protect cockle stocks. This decision was taken despite the objections of conservationists in the UK and Norway, the latter being the summer home of many of these birds. The fact that cockle numbers continued to fall after the cull was an embarrassment, suggesting that Oystercatcher predation was not the only factor at play. Fast forward another 25 years, to the start of the period considered in this paper …

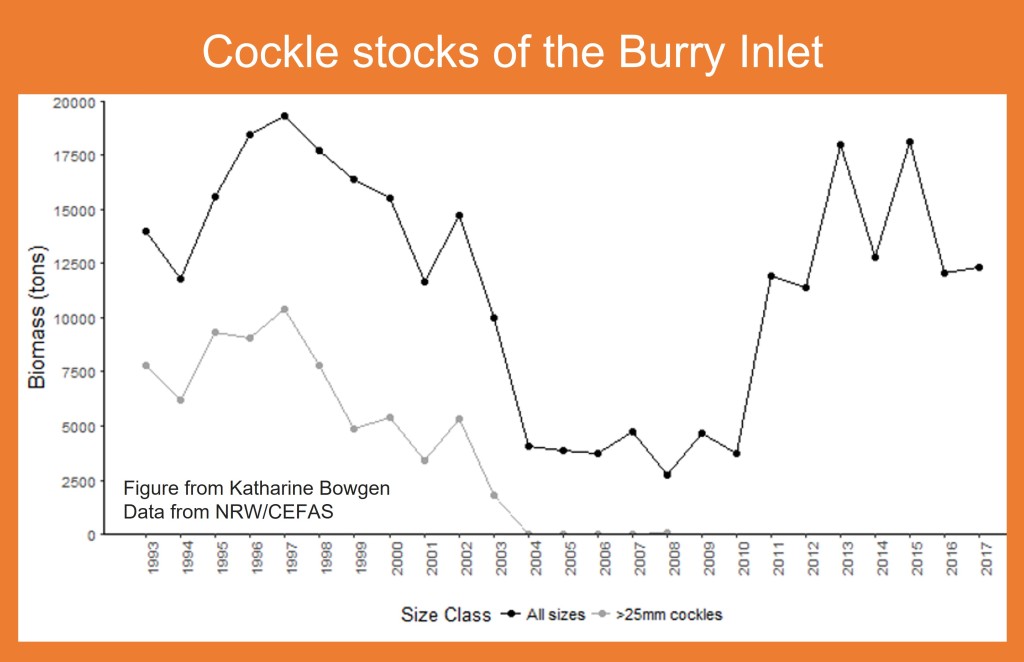

The cockle population in the Burry Inlet SPA declined from 1997 to 2004, before an abrupt ‘crash’ in stocks between 2004 and 2010 which was linked to increased mortality in older cockles, which are particularly important to commercial shellfishers. There are suggestions that losses were associated with warmer summers and sewage releases in periods of wet weather. While there has been some recovery since that period, stocks of larger cockles are still very low.

As cockles are a major prey species for Oystercatchers, the loss of larger individuals may place significant pressure on their populations, as has also been seen in the Dutch Wadden Sea and in The Wash SPA in the UK. Studies in the latter area, by BTO scientists and using data from the Wash Wader Research Group, linked declines in Oystercatcher survival and numbers to years of low cockle numbers (Atkinson et al. 2003 and Atkinson et al. 2005).

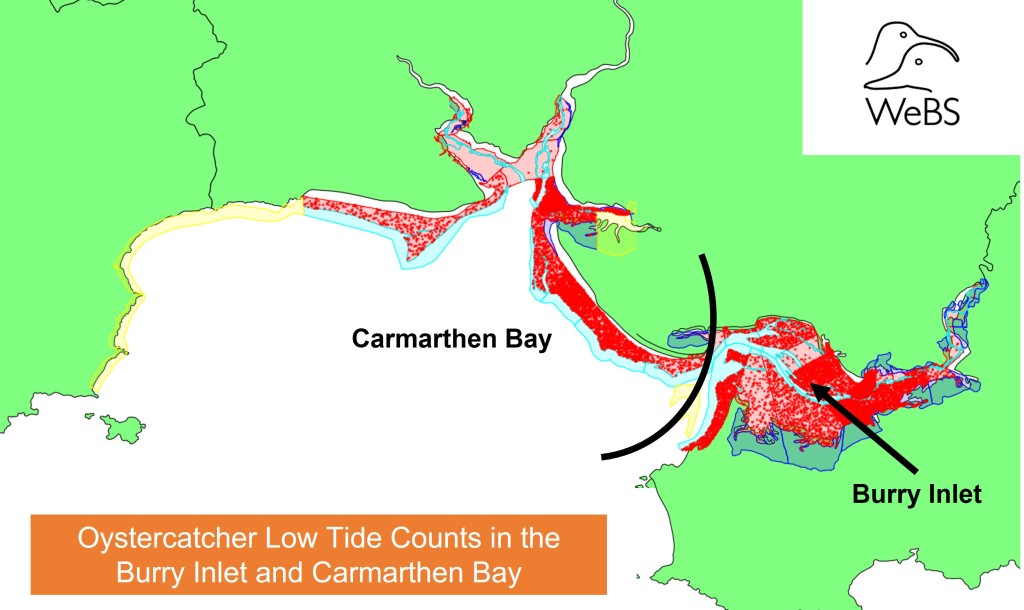

When trying to understand Oystercatcher responses to cockle changes in the Burry Inlet and the wider Carmarthen Bay SAC, Katharine Bowgen and colleagues had two main data-sets available to them. The Wetland Bird Survey, and the Birds of Estuaries Enquiry that preceded it, have provided fifty years of data on winter numbers for the Burry Inlet and other local and regional sites. The relative importance of different areas within Carmarthen Bay and the Burry Inlet were established using Low Tide Counts (see below).

Ringing operations also contributed data on the movements of marked birds, individual body masses that could be used to assess the condition of trapped birds, retrap information from which survival rates can be estimated, and opportunities to assess how many juveniles and immatures there are within samples of caught birds. November estimates of cockle biomass were available for the period from 1993 to 2008 (NRW/CEFAS).

What happened to Burry Inlet Oystercatchers?

Here are some of the key findings. Please see the paper for methods and full results. The study was funded by CCW (now NRW).

- Adult Oystercatchers were found to be in better body condition than immatures and juveniles. Non-breeders may spend three or more years in sites such as the Burry Inlet before first returning to breeding areas.

- There was considerable variation in annual body condition indices. Two features stood out. Condition was lower in 2005, the winter following the crash in cockle stocks, and improved in the following year. A similar bounce-back could be seen after a particularly cold winter (2010).

- From recapture data, apparent survival post-2000 was positively correlated with total cockle biomass. Apparent adult survival dropped from an average of 99.3% (range 98.3-99.9%) to 78.5% (range 68.5-84.3%) during the years following the crash in cockle stocks (2004), before rising back to 99.5% (range 99.0-99.9%).

- In a previous BTO report to CCW (Niall Burton, Lucy Wright et al, 2010) the survival impacts of the Burry cockle crash appeared higher. This effect was diluted with the addition of eight extra years of data presented in this paper. Shorter snapshots of data do not fully capture changes in survival rates for long-lived wader species.

- Cannon-netting Oystercatchers is not easy! The lack of consistent annual catching success and biases associated with, for instance, just catching the edge of a flock (where juveniles tend to be concentrated), are probably reflected in the fact that no recruitment patterns could be established.

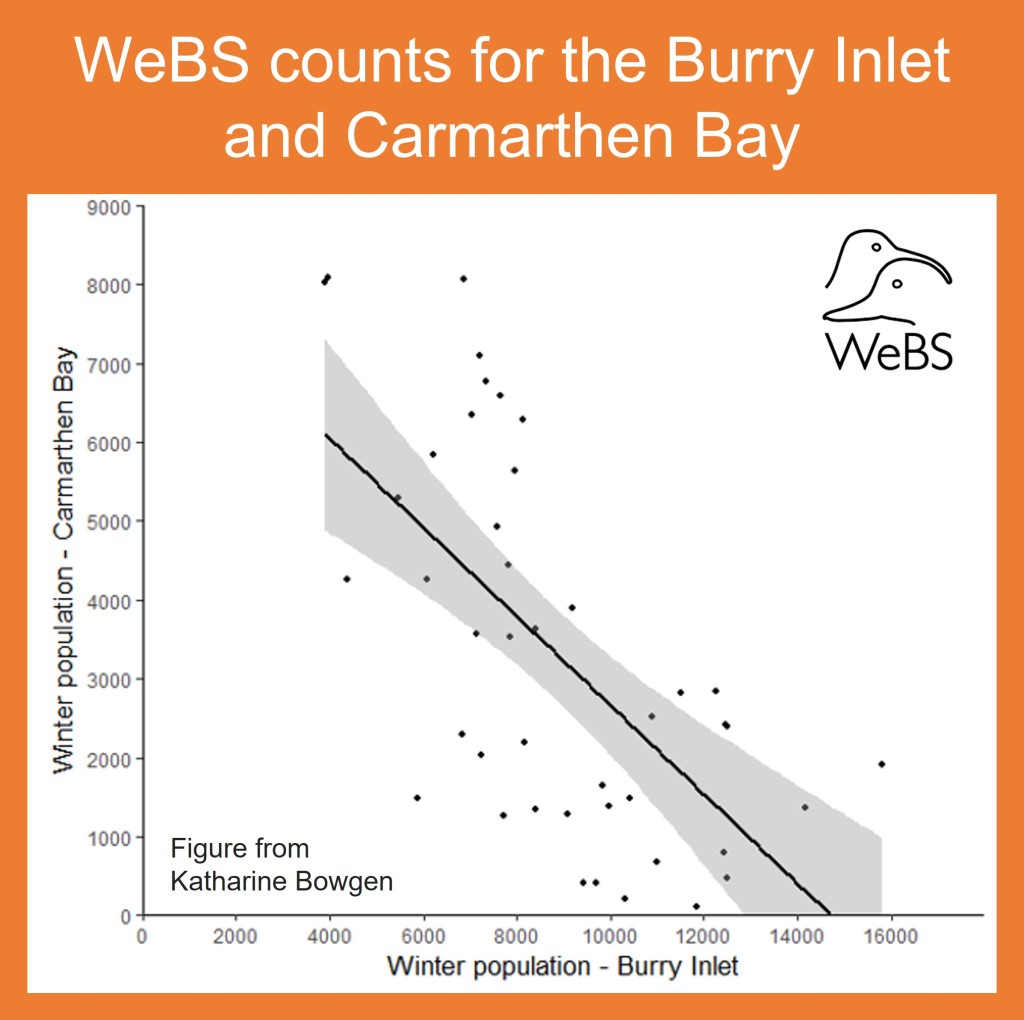

- WeBS Core Count data showed a significant long-term decrease in the population of Oystercatchers wintering in the Burry Inlet and a long-term increase in the population in Carmarthen Bay. During the period 1997 to 2017 there was a correlation of the two sets of figures – as Burry numbers declined, Carmarthen went up and vice versa (see figure below). Counts of Oystercatcher in the Burry Inlet were weakly associated with cockle biomass in the estuary. Carmarthen Bay counts were more strongly linked to Burry Inlet cockle biomass, increasing as cockle supplies dropped in the Inlet.

Take-home messages

In the study by Katharine Bowgen and colleagues, an apparently underexploited area within the Carmarthen Bay SAC became a vital resource when food supplies collapsed in the Oystercatchers’ preferred feeding area.

Understanding how birds can (and may need to) respond to changing food resources is important, given ongoing pressures from shell-fishers and the fact that the distribution of invertebrate prey stocks may be affected by climate change. The ongoing cockle decline in the Burry Inlet is of concern to both the fishermen, reliant on the stocks, and to conservation managers monitoring bird populations. This study suggests that Oystercatchers may be able to adapt during periods of stress but only if alternative foraging areas are available in the local vicinity.

The analysis of long-term datasets allows more accurate understanding of incidents such as the cockle crash investigated here and improves our abilities to manage their effects on longer-lived species such as waders. Only through long-term monitoring is it possible to fully understand the consequences of major changes in species’ resources and how individuals might adapt to cope with their impacts.

Population level effects

The following three WaderTales blogs contain information about how wintering conditions in particular study areas can affect wader populations.

In A place to roost, there is a section about the consequences for local Redshank when Cardiff Bay was permanently flooded, with links to three important papers. Birds that moved elsewhere had difficulty in maintaining their body condition in the winter following removal of their feeding habitat and continued to exhibit lowered survival rates in subsequent years.

In Travel advice for Sanderling,there is clear evidence that poor wintering conditions affect survival rates, the probability of breeding in the first summer and the timing of spring arrival in Greenland. All of these three factors can have population-level effects for the species.

In Gap year for sandpipers, we learn that Semipalmated Sandpipers may not breed every year, depending upon the condition they are in when it is time to migrate.

These three stories are all relevant to the Burry situation. Oystercatchers that were in poor condition at the end of a winter, either because they stayed in the Inlet and had fewer resources or because they moved to new sites, may not have had the resources to migrate to their breeding areas in some years or could have migrated later, either of which may reduce the number of potential breeding attempts within a season (see Time to nest again?).

Conservation implications

Although the analyses presented here were undertaken in order to understand what happened in the Burry Inlet, a site designated in part because of the high Oystercatcher counts, the authors emphasise just how important networks of sites are to wider shorebird conservation issues, especially if there is a rapid change in the quality of a core area. It is not sufficient just to protect the very best sites.

With coastal wader populations exhibiting long-term declines globally, understanding how they respond to changes in their prey is important, especially given the potential for warming seas to affect invertebrate populations. In this context, the Burry Inlet study demonstrates the value of long-term WeBS counts and the efforts of local ringers. The contribution of volunteers is warmly acknowledged at the end of the paper.

Resilient protected area network enables species adaptation that mitigates the impact of a crash in food supply. Bowgen, K.M., Wright, L.J., Calbrade, N.A., Coker, D., Dodd, S.G., Hainsworth, I., Howells, R.J., Hughes, D.S., Jenks, P., Murphy, M.D., Sanderson, W.G., Taylor, R.C. and Burton, N.H.K. MEPS. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13922

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton (@GrahamFAppleton) to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on published papers, with the aim of making shorebird science available to a broader audience.

Excellent post, as always Graham 🙂

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: Blowing Away the Cobwebs | everyday nature trails

Pingback: January to June 2022 | wadertales

Pingback: Wetland Bird Survey: working for waders | wadertales

Pingback: Wales: a special place for waders | wadertales

Pingback: WaderTales blogs in 2022 | wadertales