Turnstones feeding on discarded chips in Hunstanton – a sign of desperation or just opportunism?

Turnstones feeding with Starlings and Collared Doves at Port Sutton Bridge (Allison Kew)

I can think of three good reasons to worry about Turnstones wintering in the UK and a couple of arguments to suggest that that the species will cope – whatever problems they might encounter. On the negative side, numbers have dropped by 50% in just thirty years, they breed on the most northerly (and hence climate-sensitive) bit of available land in the northern hemisphere and we frequently see them scavenging on unnatural foods, such as discarded take-aways. On the plus side, Turnstones are long-lived birds that will eat almost anything.

Tough waders

From Time to Fly, by Jim Flegg (BTO)

The Turnstones we see around the shores of the British Isles in the winter are almost all from Greenland and the Canadian Arctic (green arrows on map). There’s a hint, in the BTO’s Migration Atlas, that east coast birds are more likely to have bred in eastern Greenland, whilst birds from western Britain tend to head further west, to arctic islands such as Ellesmere. A few Scandinavian breeders may winter here but these birds mostly turn up on spring and autumn passage (orange arrows on map).

In a 1985 paper in Bird Study, Neil Metcalfe and Bob Furness showed that 95% of Turnstone colour-ringed on the Clyde arrived back there after the breeding season, having undertaken two Atlantic crossings and bred in the High Arctic. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given this high survival rate, the BTO longevity record is over 20 years. This is higher than that for any other Turnstone ringed (or banded) as part of a European or American ringing scheme, but this record may well increase still further, now that birds wear harder, longer-lasting rings.

Checking to see what the tide has washed up (Graham Catley)

One way Turnstones can survive is to eat other birds, as we found in the winter of 1990/91, when nearly 5000 waders were found dead in south-east Britain, after a period of particularly cold weather. Although 2442 Redshank, 1357 Dunlin, 501 Grey Plover, 149 Knot, 139 Oystercatcher and 90 Curlew corpses were found on the tide-line, there were very few reports of dead Turnstones. Some of those that were still to be found on beaches were feeding on the bodies of other waders. (Further details in Clark, J.A., MPhil Effects of severe weather on wintering waders, University of East Anglia, 2002)

Turnstones are physically tough too. On one night in James Bay, Canada, I accidentally ran over one on a beach when driving a three-wheel ATV motor-bike. It was under the tyre (and me) before I had time to spot it. I stopped and picked the gravel out of its feathers and it flew off, apparently none the worse for the encounter.

Dinner is served

There’s not much of a jump from scavenging for fish bits on a jetty to waiting for chips outside a fish & chip shop (Graham Catley)

As a species, Turnstones are remarkably adaptable when it comes to their choice of food outside of the breeding season. They can be found on the most exposed of shores (feeding in breaking waves along with Purple Sandpipers), on the flat sands of estuaries (perhaps in shellfish beds with Oystercatchers), or on the receding tideline with Sanderling. Colour-ringing tells us that individuals adapt to particular feeding areas, whether these be Scottish rock-pools or under bar-tables on beaches in the Caribbean. If opportunities arise they take them – when high tides wash maggots out of seaweed beds, when cockle diggers have been disturbing cockle beds, if storms throw up shellfish onto the tideline or if a carcase washes up on a beach. There’s even an oft-quoted example of Turnstones feeding on a human corpse (Mercer, A. J. 1966. ‘Turnstones feeding on human corpse’. Brit. Birds, 59: 307).

Numbers

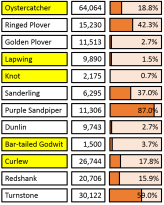

The latest winter population estimate for the UK is 51,000 Turnstones with about 20,000 of these on estuaries and the rest on the open coast-line. The species is only amber-listed on the latest UK Birds of Conservation Concern list, based on a decline of 20-30% in the 25-year period under consideration.

59% of UK Turnstone were found on open shores during the NEWS-II survey

According to the latest Wetland Bird Survey data, the UK population in 2013/14 was about the same as during the period 1974 to 1983 but, in the intervening years, numbers have risen steeply and then fallen again. Were the chosen window for conservation-listing to be 1987/88 through to 2013/14, the decline would be about 50% and the species might have been red-listed. Internationally, the Ruddy Turnstone is of ‘least concern’, when assessed against BirdLife International criteria, reflecting a wide distribution, large population and relatively shallow decline in numbers.

Given that the current trend in Turnstone numbers is very much downwards, perhaps the species should be receiving a bit more attention?

That’s a strange place to find Turnstones?

When bird species are in trouble they tend to turn up in odd places – Barn Owls hunting along roads in snowy weather, for instance – but sometimes the ‘go to’ food becomes a favourite – as we saw when Siskins started homing in on bird feeders. Turnstones are commonly found foraging in non-tidal situations and a neat paper by Jennifer Smart and Jennifer Gill aimed to work out whether they are forced to do this or they’re there because these are good options.

Catching Turnstones at dawn on the brick-weave of the dock required some lateral thinking. Note the sand bags used to make emplacements for the cannon (Allison Kew)

A flock of Turnstone on the Wash (eastern England) was first noticed feeding on the dock-side at Sutton Bridge in 1998. Over the next few winters, these birds provided an opportunity to try to work out whether this behaviour was a consequence of poor food supplies on traditional feeding areas or just opportunism. In their introduction to the paper in Biological Conservation, arising from this work, Jennifer Smart and Jennifer Gill said “Many species of shorebird typically forage almost exclusively on intertidal habitats. When such strongly maritime species choose to forage on non-intertidal habitats, it may either be a response to deteriorating intertidal conditions or to the discovery of more profitable resources in non-intertidal areas. Methods which allow distinction between these two will clearly be important for identifying problems in intertidal habitats”.

Turnstones feeding on grain and fish-meal: Allison Kew

Port Sutton Bridge is a four-berth facility on the canalised River Nene, four kilometres inland of the Wash. Although it handles a variety of cargo, the two that interest Turnstones are grain and fish-meal, quantities of which are spilt on the dock and presumably in the water. By colour-ringing individuals, using cannon netting techniques that had to be specifically adapted by the Wash Wader Ringing Group for the purpose, and counting birds at different stages of the tide, in a variety of weather conditions and over the course of the non-breeding season, Jen Smart aimed to understand how individuals were using the site.

Turnstone had first been observed using Port Sutton Bridge in January 1998, when a flock of 196 birds was present, grain exports having commenced at the port ten years earlier. In the period of the study (1997-2002) the maximum count was 576, a significant proportion of the estimated turnstone population of 600 on the Wash, according to Wetland Bird Survey data, although the Turnstones’ habit of roosting on offshore buoys over high tide (when counts take place) may make this WeBS total a slight underestimate.

Colour-rings were used to measure turn-over. Ten birds were also radio-tagged. All 9 adults split their time between mud-flats and the port area but the one juvenile was only ever recorded in or around the port (Jen Smart).

Turnstones did not head straight for the port when they returned from Greenland and Canada. Very few fed there in the period July to December and, when they did start to use the site, large numbers generally only occurred at high tide, when other food sources were unavailable, and on colder days, when the availability of invertebrates on mudflats is often reduced and energetic demands are likely to be higher. The numbers and timing indicated that the switch to the dockside arose because the non-intertidal habitats were being used to supplement the diet on the preferred intertidal mudflats.

Jen Smart spent a lot of time watching Turnstones feed at the port, collecting their droppings and sampling the food available. In the paper she clearly shows that there was more than enough food for the whole Wash population on most days, so most birds were actively choosing not to make full use of the resources available most of the time. This could have been because of disturbance on the site (although the birds tolerated people) but was more likely to be realated to actual or perceived predation risk, and the lower quality of the foods available.

Three Canadian-ringed bird were observed at Sutton Bridge. This one spent several winters in Cleethorpes, Lincolnshire (Chris Atkin)

Given that grain has a low fat content and there are high risks of predation and disturbance associated with the site, why did Turnstones choose to forage there? One possibility is that declining shellfish stocks on the Wash forced the birds to exploit alternative food sources. Within faecal samples collected on the dock, the commonest intertidal prey remains were shells of young cockles, although hard-bodied prey such as these will be more prevalent in faecal remains than soft-bodied prey. This strongly suggests that grain and fishmeal were acting as a ‘top up’. Interestingly, when there was a heavy fall of cockle spat in 2000 there was a reduction in numbers of Turnstone at the port in the next winter.

Three colour-ringed Turnstones at Heacham, 20km from Sutton Bridge (Jen Smart)

By looking at the pattern of counts, Jen Smart & Jenny Gill could infer that the port is a source of supplementary food and not a preferred resource. This allowed them to suggest that Turnstones may have been reacting to declines in intertidal prey that also affected other shorebird species on the Wash over the same period. The availability of wheat grain at Port Sutton Bridge, in addition to field and river edge habitats, appeared to have been playing a highly significant role in maintaining the internationally important status of Turnstone on the Wash. In this study, scientists were able to assess the likely cause of the habitat switch before any decline in the Turnstone population had taken place.

Implications

- Showing off a full set of 5 colour-rings (Richard Chandler)

The invertebrate populations of intertidal mudflats in NW Europe are currently threatened by sea level rise, development pressures, disease, exploitation of shell fisheries and climate changes which can alter the suitability of the habitat for particular species. The impact of these processes is often unclear because long-term, broad-scale data on intertidal invertebrate populations are rare. Changes in the distribution or species such as Turnstone, Redshank and Oystercatchers, all of which are known to switch to terrestrial habitats, may therefore often be the first indication of pressures on bird populations that have been caused by a decline in invertebrate abundance. These changes in local bird numbers can be picked up because there are regular counts of waders on estuaries, particularly by birdwatchers contributing to the Wetland Bird Survey and the associated Low Tide Counts.

Desperation or Opportunism?

Grahame Madge photographed these Turnstones in Brixham (Devon), feeding on scraps of fish & chips

So, should we be worried if we see Turnstones outside a fish & chip shop? I guess that, once an individual Turnstone has discovered that there’s an easy source of extra food on a Norfolk sea-front or under the tables of a beach bar in the Caribbean, then it’s probably going to continue to exploit these opportunities. On the other hand, if the flock is getting bigger then perhaps we should ask “why?”

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton, to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on previously published papers, with the aim of making wader science available to a broader audience.

@grahamfapppleton

Pingback: WaderTales: a taste of Scotland | wadertales

Pingback: Why do Turnstones eat chips? | wadertales – Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog

The ones in Scarborough hang around the car park waiting for chips or other tasty morsels to be discarded before the occupants drive off!

LikeLike

Pingback: Sixty years of Wash waders | wadertales

Pingback: Red Knot pay the price for being fussy eaters! | wadertales

Pingback: Disturbed Turnstones | wadertales