When an environmental impact assessment concludes that only a small number of shorebirds will be affected by a new airport, because relatively small flocks are counted during field surveys, is there an assumption that the birds encountered are always the same individuals? What if different shorebirds use the same patch of mud at different stages of the tide, at different times of day or in different seasons? How many birds might really be affected?

In a 2023 paper in Animal Conservation, Josh Nightingale and colleagues investigate the movements of colour-marked Black-tailed Godwits, to see how much they fly into, out of and around a Special Protection Area, to work out how well an Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) might assess the importance of a site that has been scheduled for development. They call for more use to be made of movement data, to assess the total impact of new developments proposed for estuaries and elsewhere.

Impact assessments

The pressures on estuaries have never been greater, as humans turn to them for transport, food, energy and to create land for new developments, such as airports. These muddy havens might be protected by national and international statutes but legally-enforceable conservation designations tend to melt away when there is money to be made, as discussed in Tagus Estuary: for birds or planes?

Developers often argue that they only want to use a small area; taking a bite out of an estuary may seem to affect only 10% (for instance) of a Protected Area – and leave 90%. Counting the birds that use that particular section might show whether this ‘10%’ contains more or fewer birds than expected and indicate whether an unacceptably high proportion of the species for which the Protected Area was designated might be affected. How much more can be learnt if we consider movements that take place within an estuary, the waves of birds that use the estuary in different seasons, the importance of the site within a Flyway and linkages to breeding areas?

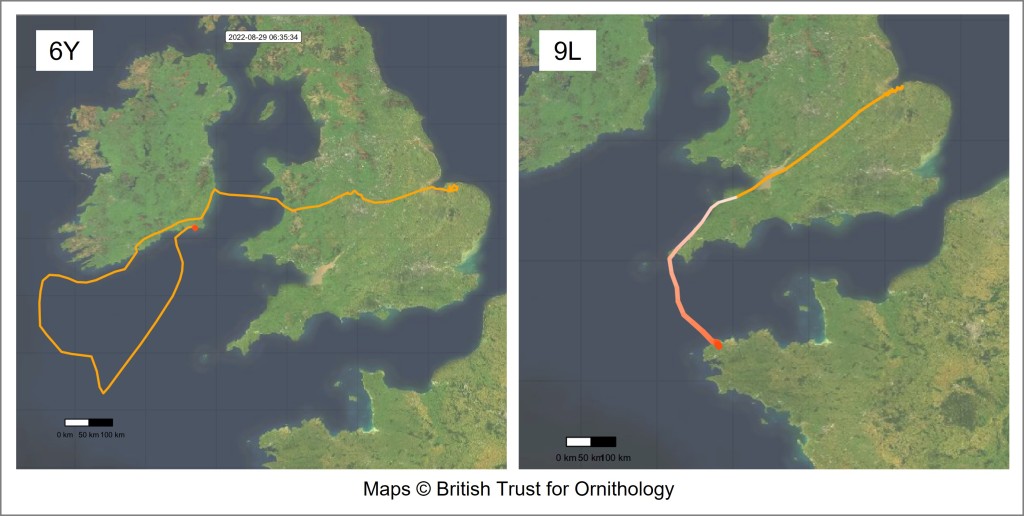

Thanks to ringing and colour-ringing, we know that Protected Areas can form networks of sites used by individuals. For example, an islandica Black-tailed Godwit might moult on the Wash (Eastern England), spend the winter on the Tagus (Portugal) and spring in Morecambe Bay (Northwest England). Thousands of limosa Black-tailed Godwits that winter in West Africa spend two months in the Tagus in spring, where they will be seen alongside Grey Plovers from Siberia, Turnstones from Canada and Bar-tailed Godwits from the Arctic regions of Scandinavia. Our knowledge of the strength and complexities of these networks is deepening, still further, thanks to satellite tracking, and the same technology provides the potential to understand more about within-estuary movements too.

Network Analysis

Information on movements of individual birds, generated by ringing, together with the development of methods such as network analysis, provides a framework in which researchers can assess the importance of Protected Areas – or threatened parts of Protected Areas. Network analysis is the study of connections. In this context, a network is simply a collection of sites, dubbed nodes, linked by connections known as edges, which may have varying directions or strengths.

In pictorial terms, ‘thicker’ edges indicate that more birds connect two nodes. When assessing connectivity, the researchers considered the number of other nodes each node is linked to and the variety of pathways between nodes.

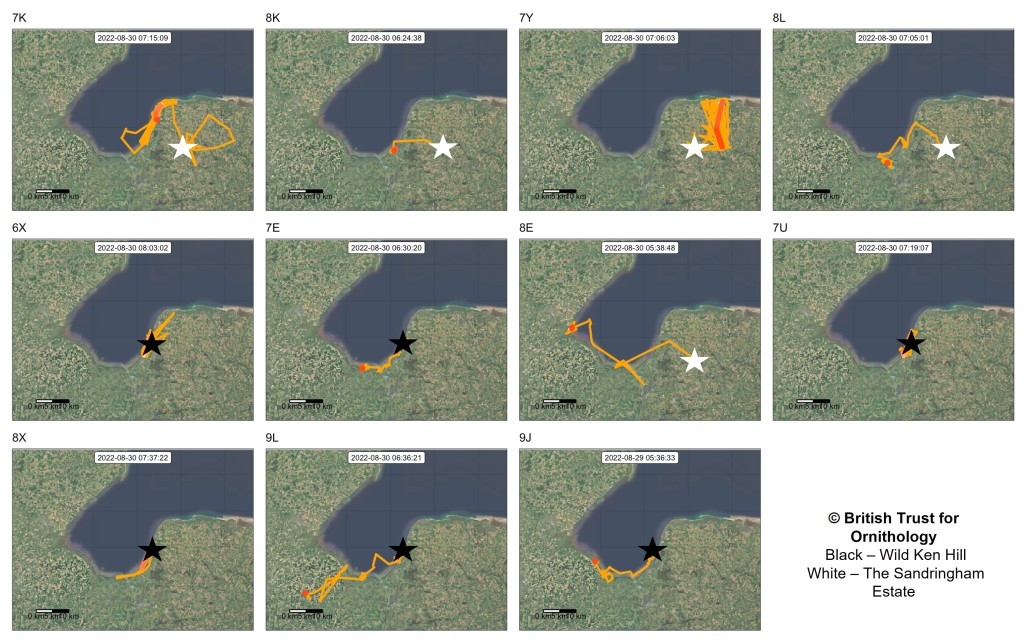

Despite being powerful and flexible, network analysis is currently used less by conservation practitioners than by academics, and much of their work is at landscape- or regional-scales. In a 2023 paper, Josh Nightingale and his colleagues adjust the focus, to see how network analysis might explain what is happening within and around a Protected Area – information that is valuable when trying to assess conservation implications of planning decisions. They use movement data to reveal the range of sites used by individuals, and thus the susceptibility of those individuals to a local development.

Network analyses can reveal which sites are most important to population-level connectivity, or the impact on connectivity of losing one or more sites. These results can be combined, to calculate the ‘impact footprint’: how many individuals use the impacted area and how do their movements connect with neighbouring sites (inside or outside the Protected Area). By representing movements between sites in a network, practitioners can gain a more accurate picture of how the effects of a localized impact may be felt at connected sites. This information can then be used to determine whether populations or habitats are impacted, and thus inform policy decisions.

Applying a Network Analysis framework to the Tagus

The Tagus Estuary, on whose banks Lisbon sits, is Portugal’s largest wetland and the country’s most important site for many waterbird species. Part of the estuary is designated under the EU Birds Directive as a Special Protection Area (SPA), with a smaller Ramsar Site at its core. The SPA excludes several of the estuary’s high-tide roosts, which consequently lack legal protection and are vulnerable to development, erosion and other threats.

The Portuguese Environment Agency has issued an Environmental Licence, approving plans to construct an international airport in the heart of the Tagus estuary, on a site overlapping part of the SPA. The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), conducted for the development, considers the main threat to bird conservation to be noise disturbance, with an aeroplane taking off or landing every 2.5 minutes and flying at low altitude (<200 m) over the SPA (see article by José Alves in Wader Study). Such disturbance can cause birds to take flight, with consequent increases in daily energy expenditure. The effect can be seen even when the airport has been operational for decades (van der Kolk et al). Airport-related disturbance close to wetlands has been shown to influence the distribution of waterbird communities (Celdrán & Aymerich).

The predicted impact of the Montijo airport development varies, depending upon the threshold of noise sensitivity assumed. Although it has been shown that waterbirds alter their behaviour when subjected to noises above 50 dB(A) (see Wright et al., the study used as a reference for the EIA), the Environmental Licence for Montijo Airport only considers relevant areas impacted by over 65 dB(A). Crucially, movements of birds within, to or from the Protected Area were not considered.

To assess how network analysis might explain the real impact of the airport, Josh Nightingale and his colleagues focused on the Black-tailed Godwit, a species for which the Tagus SPA had been designated and for which a large amount of colour-ring data was available. They wanted to answer these questions:

- How much of the local godwit population is protected by the Protected Area during the year, and how much does this overlap with the area to be impacted by development?

- How much of the Tagus is used by birds from the Protected Area, and by birds from the area that would be affected by low-flying aircraft?

- Which sites are linked most closely to others and how might the predicted development weaken connections between sites across the Tagus estuary?

Assembling the data sets

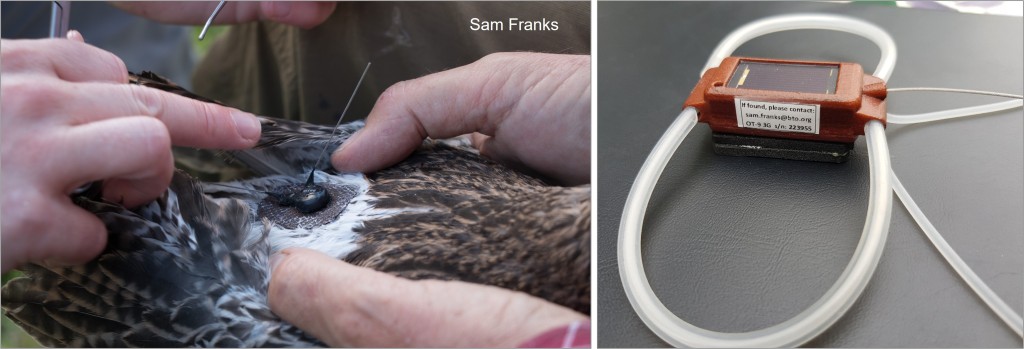

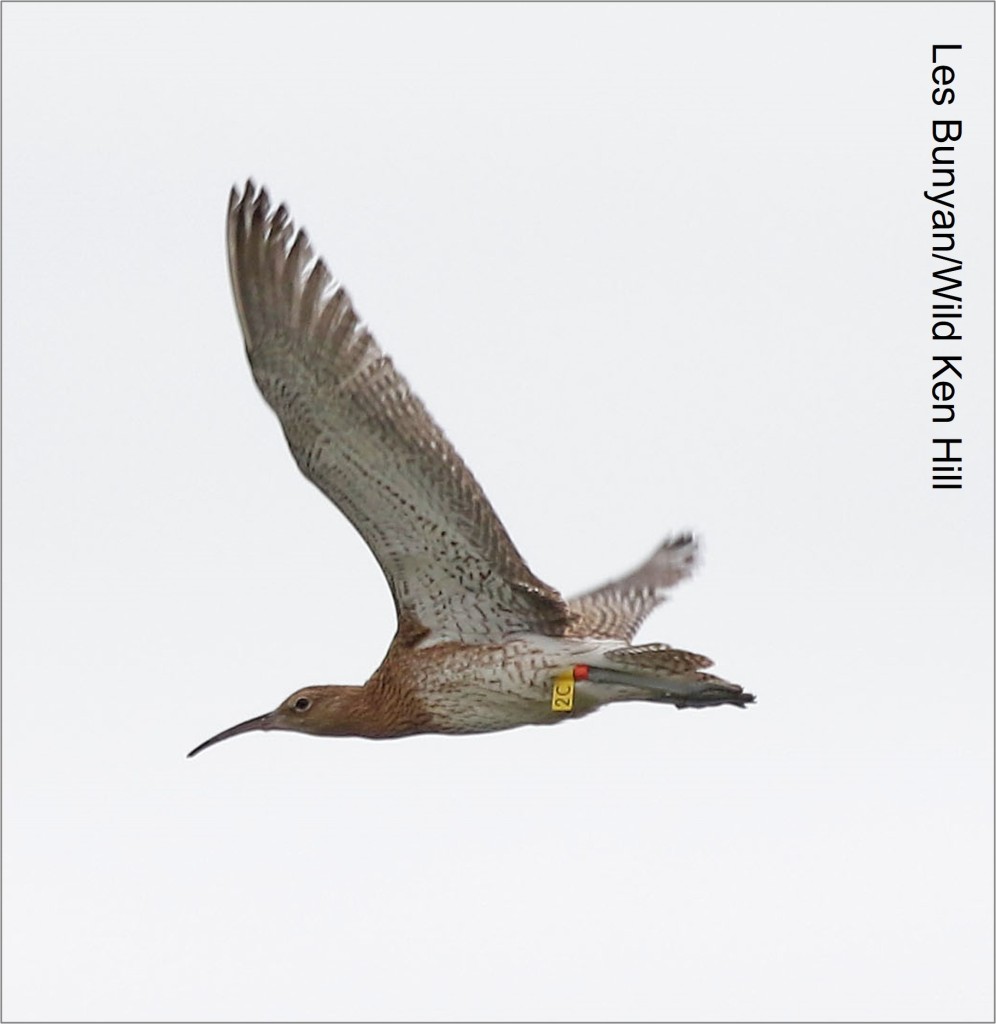

Islandica Black-tailed Godwits have been intensively studied since 1993, when the first birds were colour-ringed. The datasets used in these analyses comprise sightings of birds ringed in Iceland, on the Wash (Eastern England) and in the Tagus (Portugal). Sightings of these colour-ringed birds have been reported by thousands of observers across the whole range of the subspecies. To get a flavour of the importance of these reports (and the dedication of birdwatchers) read Godwits and Godwiteers.

Within the Tagus Estuary, the focus was on marked birds reported between 1st January 2000 and 1st July 2020. Observations were recorded at 30 sites that were visited at least once during early and late winter, and more frequently since October 2006. To reduce the potential risk of observation error, only sites at which an individual was recorded at least twice during its lifetime were assigned to that individual.

To assess site-level noise-exposure that birds might experience, Josh Nightingale and colleagues analysed their data based on the areas in which godwits might encounter noise levels of 55 dB(A) and 65 dB(A). Full methods used in the network analysis are given in the paper.

Impacts on Black-tailed Godwits

Individual Black-tailed Godwit are conservative in their habits. At a Flyway scale, they typically use only four or five different sites per year, with this annual schedule remaining constant over up to twenty years (as discussed in Generational Change). Josh Nightingale found similar consistencies within the Tagus Estuary. Most of the 693 individually-tracked godwits were found at six or fewer sites (of the thirty available), even when observed for a decade or more. 82.8% of individual godwits used sites inside the SPA and 67.7% used sites outside the SPA. There was seasonal variation in the protection footprint of the SPA, which was three times as important in October-December as it was in January-March

In the early part of the winter, islandica Black-tailed Godwits are most likely to be found feeding on the estuary itself, with many moving to inland feeding sites, particularly rice fields, in January to March. Much of the area that would be impacted by the noise from aircraft is over the estuary so it is not surprising that the impact footprint is greater in October to December, when disturbance is estimated to affect 68.3% of the godwits, if a threshold of 55 DB(A) is used, or 40.7% based on 65 dB(A).

When the researchers considered individual movements within the same winter, they found that birds from within the Protected Area visited 14 out of 17 of the sites that lie outside the Protected Area. A flock of roosting or feeding birds seen well outside the SPA is very likely to include birds that also feed in the SPA. There were similar levels of connectivity from unimpacted sites across the estuary to the 55 dB(A) impact zone. The most centrally connected site, the Giganta rice fields, is outside the SPA but within the 55 dB(A) affected area – hence unprotected and highly impacted.

Turning the focus to the area of the estuary that will be most impacted by aircraft noise, the researchers found that 68% of islandica Black-tailed Godwits in the Tagus will be affected. This is higher than an estimate of between 0.5% to 5.5% that was quoted in the EIA. The lower estimate is based on a 65 dB(A) threshold, rather than 55 dB(A), uses old counts and does not consider bird movements. This implies that the effect of the airport on Black-tailed Godwits will be twenty times as large as considered in planning decisions. And this discrepancy is just for one of the species for which the Tagus is designated as an SPA and Ramsar Site.

The paper contains a detailed analysis of how the protected network would be degraded by the new airport, through loss of key sites and by taking out edges that link current nodes that will be affected by disturbance. Overlaying the 55 dB(A) on the current Tagus network has the potential to reduce connectivity between sites by nearly 30%, effectively partially blocking the free flow of birds around the estuary.

Conservation implications

The footprint approach developed by Josh Nightingale is really neat. For the Tagus, it shows that over half of the colour-marked Black-tailed Godwits use sites outside the Special Protection Area, as currently defined, and that the majority of the most important sites that provide connectivity across the estuary are also unprotected.

Using Black-tailed Godwits as an example, the research team show that the EIA may have underestimated the impact of the airport by a factor of about 20. When disturbed by aircraft or scared off to reduce strike risk, more energy will be expended and some birds may permanently desert key feeding or roosting areas. Research elsewhere has shown that displacements can have temporary and even long-term effects on the survival rates of affected individuals.

To quote from the paper, “Protected Areas are a critically important conservation tool to protect populations, especially as ranges shift in response to climate change. To secure the integrity of PAs and the populations they support, we need to be able to accurately assess the impacts of developments inside and outside PA boundaries. Animal-tracking data offer exciting and feasible opportunities to assess PAs’ contributions to protecting populations of mobile species and the potential for adverse effects of external developments on PA integrity.”

Conservation beyond Boundaries: Using animal movement networks in Protected Area assessment. Josh Nightingale, Jennifer A. Gill, Böðvar Þórisson, Peter M. Potts, Tómas G. Gunnarsson & José A. Alves. Animal Conservation. Doi: 10.1111/acv.12868.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton (@GrahamFAppleton) to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on published papers, with the aim of making shorebird science available to a broader audience.