Over the last fifty years, a range of methods have been used to estimate the annual survival rates of waders/shorebirds. These estimates are based on many hours of patient catching and colour-ring reading, making each one too valuable to discard. How can estimates generated in different ways be combined and what can these estimates tell us about the way in which survival rates vary between species and in different parts of the world?

Over the last fifty years, a range of methods have been used to estimate the annual survival rates of waders/shorebirds. These estimates are based on many hours of patient catching and colour-ring reading, making each one too valuable to discard. How can estimates generated in different ways be combined and what can these estimates tell us about the way in which survival rates vary between species and in different parts of the world?

Survival rates are important

As revealed in this previous WaderTales blog, Waders are Long-lived Birds, larger species survive for 30 years or more and even smaller species, such as Ringed Plover (above), manage 20 years. With relatively low annual breeding productivity, maintaining a high survival probability of typically between 70% and 90% per annum is essential for population stability. If the annual survival figure for adults drops, as discussed in this blog, Wader declines in the shrinking Yellow Sea, this can have rapid and serious consequences for population levels.

Different survival measurements

Cups, ounces and grams; Celsius, Fahrenheit and gas mark; if we all used the same measurements and systems when cooking, life would be much simpler. It turns out the same is true when measuring annual survival rates for waders/shorebirds.

Measures of annual survival rates can be hard to obtain because large-scale, long-term tracking of individuals is not easy and the resulting data contain many inherent biases. There are many different ways to estimate survival rates.

Return rates: the proportion of marked individuals that are recaptured/resighted in subsequent years. Any bird that changes its location before the next resighting period will reduce the estimate of annual survival for the study population, even though it may still be alive.

Return rates: the proportion of marked individuals that are recaptured/resighted in subsequent years. Any bird that changes its location before the next resighting period will reduce the estimate of annual survival for the study population, even though it may still be alive.

Mark-recapture models: a range of different methods are available that allow the researcher to account for the effort that goes into looking for marked birds. Effectively this apportions the probability of missing a marked bird and the bird not being alive.

Dead recovery models: survival rate is inferred from the number of dead, ringed birds that are recovered. At its simplest, this does not take account of the number of birds ringed.

Complex modelling: used to separate apparent survival estimates into ‘true’ survival and site-fidelity, using live encounters and resighting/recovery rates. This helps to take account of the probability of birds leaving monitored sites.

Tracking studies: Survival estimates from radio-telemetry tracking studies are only available for a very limited number of shorebird species and for short periods. These measures were not included in this study.

Wouldn’t it be great if someone pulled together all of the available estimates of survival, produced by different methods? That’s what Verónica Méndez has done, with José Alves (University of Aveiro, Portugal), Jennifer Gill (University of East Anglia, UK) & Tómas Gunnarsson (University of Iceland) in Patterns and processes in shorebird survival rates: a global review, published in IBIS. (Click on the title to link to the paper).

In the paper, the authors have reviewed published estimates of annual adult survival rates in shorebird species across the globe, and construct models to explore the phylogenetic, geographic, seasonal and sex-based variation in survival rates. The supplementary material includes an appendix detailing all of the available published estimates.

Key findings

Using models of 295 survival estimates from 56 species, Verónica and her colleagues showed that:

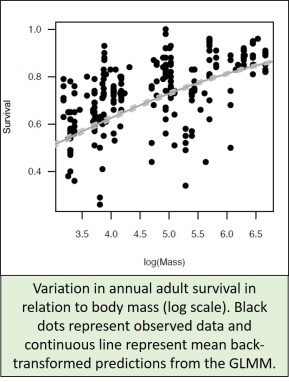

As expected, survival rates for larger-bodied species are higher than for smaller species.

As expected, survival rates for larger-bodied species are higher than for smaller species.- Survival rates calculated from return rates of marked individuals are significantly lower than estimates from mark-recapture models.

- Annual survival tends to be slightly higher when estimated in wintering populations, but the difference from breeding season estimates was not significant.

- As has been shown in many individual studies, female shorebirds often have lower survival rates than males, although this difference can be exaggerated if survival estimates are based on return rates and females are less site-faithful.

- Survival rates vary across flyways, largely as a consequence of differences in the groups of shorebirds that have been studied and the analytical methods used.

Published estimates from the Americas and from smaller shorebirds (Actitis, Calidris and Charadrius spp) tend to be underestimated.

Published estimates from the Americas and from smaller shorebirds (Actitis, Calidris and Charadrius spp) tend to be underestimated.- By incorporating the analytical method used to generate each estimate within the models, the authors show that it is possible to ‘correct’ survival estimates, according to method used and genus, for a total of 52 species of 15 genera.

What about Slender-billed Curlew?

I asked Verónica whether it might be possible to estimate the annual survival rate for an adult Slender-billed Curlew. If there is a relict population somewhere then that’s a figure that’s going to be important to scientists who are trying to find them. Verónica said that these methods won’t provide a species-specific estimate but, given that the survival rate for the Numenius family is 0.71 ± 0.045 (standard error), the predicted survival should be somewhere within the range 0.62 to 0.79. If Slender-billed Curlews are no longer breeding successfully then half of any remaining adults will be disappearing every couple of years. That’s a sobering thought.

Conservation Imperative

A large number of the world’s shorebird populations are in decline and reduced annual survival rates seem to be a cause for concern in some parts of the world. Although it is impressive that the research team were able to find 295 survival estimates for this paper, I reckon that the data exist to calculate a whole lot more. Each of these extra results might not produce a novel paper but it would be great to see them published somewhere, as brief notes in the journal Wader Study for instance. That way, they will be available as bench-marks, next time researchers are worried about what appears to be a lowered level of annual survival. Meanwhile, here’s hoping that colour-ring readers will continue to provide sightings of birds for decades to come – there’s no substitute for long-term data-sets.

A large number of the world’s shorebird populations are in decline and reduced annual survival rates seem to be a cause for concern in some parts of the world. Although it is impressive that the research team were able to find 295 survival estimates for this paper, I reckon that the data exist to calculate a whole lot more. Each of these extra results might not produce a novel paper but it would be great to see them published somewhere, as brief notes in the journal Wader Study for instance. That way, they will be available as bench-marks, next time researchers are worried about what appears to be a lowered level of annual survival. Meanwhile, here’s hoping that colour-ring readers will continue to provide sightings of birds for decades to come – there’s no substitute for long-term data-sets.

This is an IBIS Open Access Review

This is an IBIS Open Access Review

Verónica Mendez has written a blog about the methods used in her paper for the BOU blog series.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton, to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on previously published papers, with the aim of making wader science available to a broader audience.

Pingback: Wader declines in the shrinking Yellow Sea | wadertales

Pingback: Bar-tailed Godwits: migration & survival | wadertales

Pingback: Waders are long-lived birds! | wadertales

Reblogged this on Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: WaderTales blogs in 2018 | wadertales

Pingback: Winter territories of Green Sandpipers | wadertales

Pingback: Not-so-Common Sandpipers | wadertales

Pingback: Travel advice for Sanderling? | wadertales

Pingback: Coming soon | wadertales

Pingback: The First Five Years | wadertales

Pingback: Gap years for sandpipers | wadertales

Pingback: England’s Black-tailed Godwits | wadertales

Pingback: More Curlew chicks needed | wadertales

Pingback: Dunlin: tales from the Baltic | wadertales

Pingback: How many shorebirds use the East Asian-Australasian Flyway? | wadertales