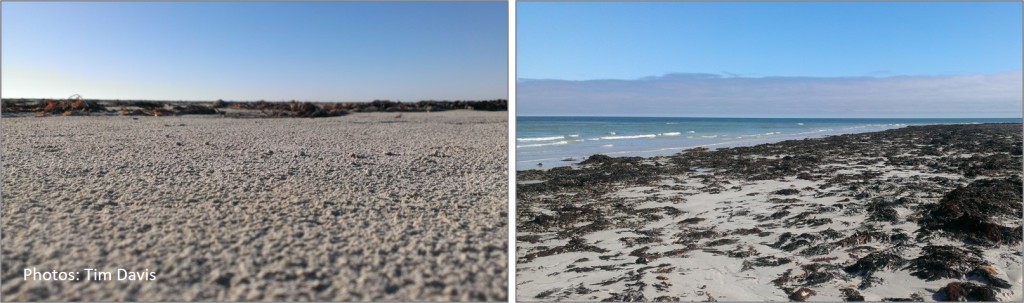

Tidewrack has an image problem. Who wants to see a dark line of seaweed on a beach of white sand or to smell rotting beds of kelp in enclosed bays? Shorebird conservationists may understand the feeding opportunities that are provided by fresh and older seaweed but, for tourist boards, tidewrack is something that needs to be cleared away.

It turns out that tidewrack is not just a biodiverse habitat; the mere presence of seaweed creates spaces in which waders can roost and find shelter. In a paper in the Journal of Applied Ecology, Timothy Davis & Gunnar Keppel get down to Turnstone-level, to investigate the important microhabitats within different forms of beach-cast wrack.

An Australian autumn

Readers in the northern hemisphere may well have seen wintering waders sheltering in the lee of clumps of tidewrack, as a gale blows snow and sand across a beach. At Danger Point, about half-way between Melbourne and Adelaide on the coast of Australia, conditions are somewhat different, with December and January temperatures topping 30°C, conditions in which waders must try to avoid over-heating. By April, when the Davis & Keppel study was carried out, conditions were autumnal, with cool mornings. Three of the species that might be seen on a European beach were present – Turnstone, Sanderling and Bar-tailed Godwit – but with the addition of Curlew Sandpipers and Red-necked Stints, that were about to depart for Siberia, and Double-banded Plovers that breed in New Zealand.

What might waders be looking for?

The research team was interested in the range of microclimates available on beaches with beach-cast wrack, to investigate the link between microclimates and microhabitats and how they are used by waders. They expected to find warmer temperatures and higher humidity on aged wrack, due to advanced decomposition, and ameliorated conditions where wrack deposits provided shelter from prevailing winds. They predicted that waders would use microclimates that could reduce energy loss.

Observations

Data on temperature and humidity were collected by creating miniature Stevenson Screens – hollow white practice golf balls with iButtons inside them, attached to short bamboo canes, so as to be 10 cm above the substrate surface. If interested in conducting this sort of study, it would be sensible to read the methods section of the paper. Sample points were on bare sand, in areas with fresh wrack deposited on the sand and in beds of old tidewrack. Based on surrounding features and observations of prevailing winds, sample points were classified as sheltered or exposed.

Instantaneous scan sampling was used to classify migratory shorebird behaviour for the entire Danger Point study area (i.e., the area over which the microsensors were placed) at 15 min intervals on four days during April, as birds were preparing to migrate. Birds were classified as roosting (loafing, sleeping or preening) or as foraging on one of the three substrate types.

Variability of microclimate

As expected, there were significant differences among the three substrates (sand, fresh wrack and aged wrack) for mean, maximum and minimum temperature and absolute humidity. The temperature above the surface of aged wrack was consistently higher than elsewhere, with one notable exception: in the early mornings, when newly deposited seaweed retained some of the heat from the warmer ocean, temperatures were warmer on fresh wrack than on sand and aged wrack. For aged wrack, humidity was highest above deeper beds.

Bird Behaviour

Six species of wader were studied and included in ‘all waders’ counts but there were insufficient sightings of Bar-tailed Godwit, Curlew Sandpiper, Ruddy Turnstone and Sanderling for separate analyses. The main focus was upon Red-necked Stint (64.0% of observations) and Double-banded Plover (31.4%).

- Roosting birds were recorded on aged wrack 16 times more frequently than sand, and three times more than on fresh wrack.

- Foraging birds were observed more than four times as often on aged wrack, when compared to fresh wrack or sand.

- However, roosting on fresh wrack was more frequent in cooler, early-morning temperatures, for all waders and for the Double-banded Plover, when considered separately. Neither temperature nor absolute humidity were significant predictors of the proportion of Red-necked Stints roosting in areas with fresh wrack.

- Foraging by waders (in general) and Double-banded Plover (in particular) was also more common within fresh deposits of wrack when temperatures were low and particularly if humidity was high. For Red-necked Stint, temperature alone predicted whether they were more likely to feed on fresh wrack, rather than aged wrack.

The importance of microhabitats

The authors show that sandy beaches with beach-cast wrack provide a complex mosaic of microclimates/habitats across differing substrates. Birds seem to exploit the microclimatic variation by using microhabitats that minimise energy expenditure, as both foraging and roosting were most likely to occur on the substrate providing the warmest, most energy-efficient conditions at the time.

There is well-documented evidence that food availability increases as seaweed decays, because wrack-beds provide homes for invertebrates, particularly developing larvae. This explains a predominance of foraging on aged wrack, which is likely to provide the best feeding opportunities. The key finding in this study is that tidewrack on sandy beaches provides important additional benefits for waders, by providing shelter and warmth. This may be particularly important when birds are fattening up for the next leg of a migratory journey. It is particularly interesting that, early in the morning, Double-banded Plovers and Red-necked Stints foraged within fresh wrack, the warmest available substrate at that time. Perhaps the effect of microclimate (temperature, humidity & shelter) might be usefully studied in other circumstances in which waders feed and roost?

The bigger picture

When considering the role that coastal ecosystems play in the lives of waders, the main conservation focus has been on estuaries, as for instance discussed in Wader declines in the shrinking Yellow Sea. The open coastline is under threat too, squeezed by rising sea levels, battered by more frequent storms, polluted by plastic etc. In some areas, waders that use these habitats outside the breeding season are also prone to human (and canine) disturbance, as described in this Turnstone study.

Alongside more general habitat degradation, there are specific threats to tidewrack habitats along the coastline. This starts offshore, with the harvesting of stands of growing kelp, and continues when fresh tide-wrack is collected or cleared from shorelines. In 2018, it is estimated that 15,000,000 tonnes of brown algae were removed, globally. Traditionally, rotted tidewrack has been used as a fertiliser on nearby fields but most of the current output is collected when fresh and used to produce alginates, for food manufacture and biomedical purposes. Increasingly, attention is turning to use in biofuels, which has the potential to greatly increase the demand for seaweed.

Whilst the food, biomedical and energy industries see value in tidewrack, the tourist industry appears to see it as an untidy nuisance that spoils the image of a pristine beach. Who knows how much tidewrack is removed from beaches during daily grooming sessions or dug out of wader-rich corners before the start of the tourist season? If the image of what constitutes a welcoming beach is to be changed then perhaps there needs to be a focus on the interest that seaweed adds to a tideline walk – as visitors collect shells and look for amber, sea-coal and egg-cases. Is this naïve; have cotton buds, bottles and plastic sullied the image of tidewrack? Should we share more photographs of Sanderling chasing through seaweed-flecked spume and flocks of waders ‘chilling’ on banks of beautifully lit seaweed, instead of the barren white beaches that are used in holiday adverts?

As Timothy Davis and Gunnar Keppel conclude: “Beach-cast wrack created a complex mosaic of unique microclimates varying in space and time, which seemingly allowed shorebirds to minimize energy expenditure, by selecting the thermally most favourable habitats for roosting and foraging. Removal of beach-cast wrack therefore reduces habitat quality and increases energy expenditure and resources in shorebirds and may contribute to the observed decline of migratory shorebird species globally. Management of coastal ecosystems and shorebirds therefore needs to maintain fine-scale environmental heterogeneity.”

Paper

Fine-scale environmental heterogeneity is important for conservation management: beach-cast wrack creates important microhabitats for thermoregulation in shorebirds. Timothy John Davis & Gunnar Keppel. Journal of Applied Ecology. April 2021

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton (@GrahamFAppleton) to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on published papers, with the aim of making shorebird science available to a broader audience.

Brilliant Graham

Many thanks for hour blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Beach-cast algae and seagrasses are essential for shorebirds – Biodiversity in Oceania

Reblogged this on Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: WaderTales blogs in 2021 | wadertales