Detailed studies of a small number of Stone-curlews, breeding in Breckland in the east of England, give some clues as to how to provide the right habitat mix for these big-eyed, nocturnal waders. Increasing structural diversity, by ploughing and/or harrowing areas of grassland, can create an attractive network of nesting and foraging sites for breeding and non-breeding adults.

In a 2021 paper in Animal Conservation, Rob Hawkes and colleagues from the University of East Anglia, RSPB and Natural England give us insights into the daily lives of Stone-curlews nesting in the dry grasslands of East Anglia. By fitting five individuals with GPS tags and following their movements they were able to establish which habitats are used at different stages of the breeding season.

The Stone-curlew is the only migratory member of the thick-knee family. England is at the north-western limit of a breeding range that stretches east to the steppes of Kazakhstan, with birds wintering in southern Europe, North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian sub-continent. Most English birds spend the winter months in Spain, Portugal, Morocco or Algeria but a small number are known to cross the Sahara. Stone-curlews return to East Anglia in March and April.

During the twentieth century, numbers of Stone-curlew across Europe fell significantly, as mechanized farming expanded. The East Anglian population had dropped to fewer than 100 pairs by 1985 and it took huge conservation efforts to increase this to 200 pairs. Breeding birds are now typically to be found in sparsely-vegetated ground, often in spring-sown crops, on dry heathland or in semi-natural grassland areas, including those used for military training. Preferred food items, such as earthworms, soil-surface invertebrates, slugs and snails, are easier to find in areas of bare and broken ground than in thick grass, so grazing is an important part of conservation action on heaths and in grassland areas.

The UK’s migratory Stone-curlew population has received a huge amount of conservation support, on the back of detailed studies of the species’ breeding ecology (Green et al. 2000). Tremendous efforts have been made to maximise chick production in farmland, with conservation staff and volunteers working with farmers to monitor breeding pairs, so that they can protect nests and chicks during crop-management operations. In the long term, however, such interventions are too labour-intensive to be sustainable. Can equivalent benefits accrue if more Stone-curlews nest successfully in semi-natural grassland, where the costs of conservation subsidies are lower than in intensively farmed arable cropland?

The study that is reported in the 2021 paper in Animal Conservation took place in an extensive area of semi-natural grassland (nearly 40 km2) that is surrounded by a mosaic of arable farmland. The aim was to understand whether ploughing or harrowing patches of grassland can provide suitable foraging areas, and which other habitats are important.

Tracking Stone-curlews

Stone-curlews are predominantly nocturnal feeders so some form of remote tracking device was needed to understand their movements. GPS loggers were fitted to five adult Stone-curlews during the breeding season. Individuals were caught at night using small, beetle-baited, elastic-powered clap-nets or in the daytime using nest-traps. Each individual was fitted with a 5.2 g solar-powered nanoFix Geo PathTrack GPS tag and an external whip antenna. GPS data were downloaded to a remote base station through a radio connection. Tagged birds were visited at least once a week to establish whether they were still nesting, if they had chicks or had finished breeding.

Where did they go?

One, two and three hectare plots of disturbed ground had already been created within Breckland’s grassland and heathland areas, prior to this study, as described in the paper and discussed in the blog Curlews and foxes in East Anglia. It was already clear that these plots were favoured as nesting sites but does disturbed ground also provide additional feeding opportunities for adult birds – including pairs nesting nearby on arable fields?

Three male and two female Stone-curlews were tracked for more than nine weeks (67 to 102 days), yielding 510 GPS fixes during nesting and 1371 post-breeding. There were some fixes in the pre-nesting phase and also during the chick-rearing phase but too few to be considered for analysis. Analytical methods are detailed in the paper.

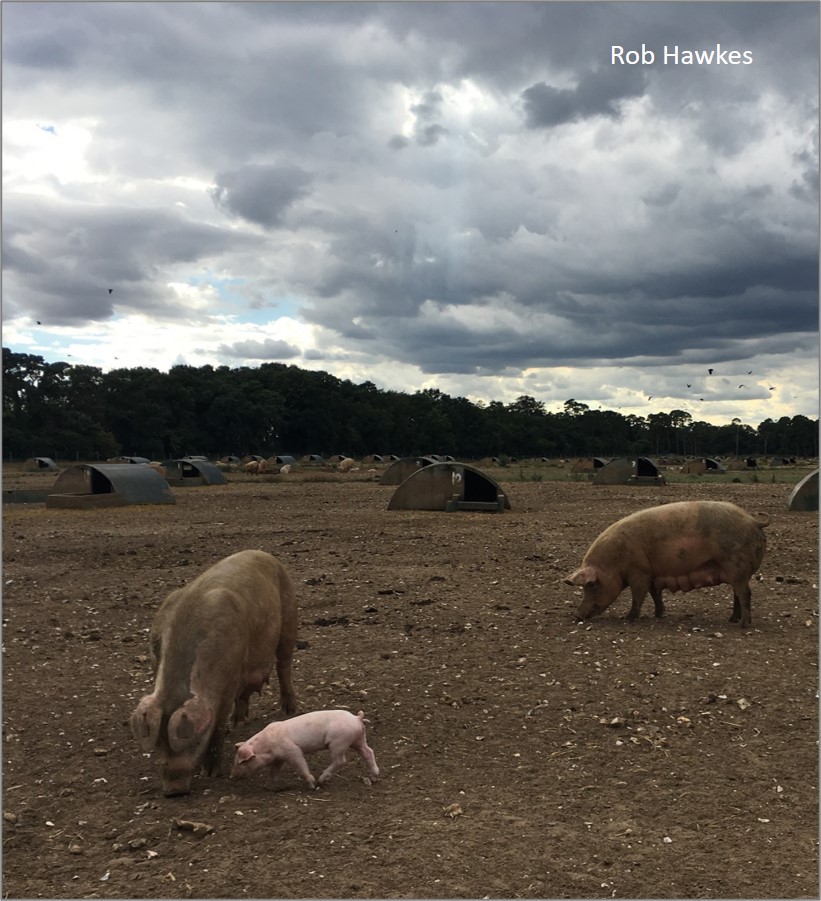

During the nesting period, what was presumed to be the off-duty bird of each pair was found within 1 km of the nest on 90% of fixes. The mean distance from the nest during daytime feeding was about 100 m but, at night, tagged birds travelled five times as far, on average. They travelled furthest when heading for pig-fields and manure heaps.

- Relative to closed, undisturbed grassland, nesting Stone-curlews were two- to three-times as likely to forage on disturbed-grassland during night and day, but especially during the day.

- Night and day, ‘sugar beet or maize’ fields were used more than unmodified-grassland but similar to disturbed-grassland.

- Nocturnally, Stone-curlews were ten-times as likely to use ‘pig fields or manure heaps’, when compared to undisturbed grassland.

- The furthest distance travelled was just over 4 km, which is further than previously thought.

In the post-breeding period, tagged birds travelled up to 13 km to forage, with 90% of nocturnal foraging locations found to be within 5 km of day-time roosting sites.

- Tagged birds were approximately 15-times as likely to use either disturbed-grassland or arable fallows when compared to undisturbed grassland.

- Use of the category ‘pig fields or manure heaps’ was nearly as strong (factor c. 10), in comparison to undisturbed grassland.

- Open crops in the categories ‘sugar beet or maize’ and ‘vegetable or root crops’ were also used more than undisturbed-grassland (factor c. 2).

Conservation messages

In England, there has been a long-term focus on trying to maximise Stone-curlew productivity within arable farmland, especially in East Anglia but also in Wessex. As suggested earlier, this is expensive – foregone production requires high subsidies and interventions by conservation staff are time-consuming. A French study, written up in Ibis by Gaget et al., seriously questions the viability of Stone-curlew populations within intensively managed arable farmland, even with conservation support. Given these problems, should conservation efforts focus on supporting and building up grassland populations?

In a previous tracking study, thirty years previously, Green at al. found that short semi-natural grassland provided suitable foraging habitat for Stone-curlews. Much has changed in Breckland in the intervening period, with the collapse of the rabbit population and an increase in the amount of outdoor pig-rearing. As the short swards of rabbit-grazed grassland have disappeared, Stone-curlews seem to have increasingly taken advantage of alternative opportunities offered in pig fields.

Previous attempts to replicate the grazing efforts of rabbits have involved increasing livestock numbers but this study shows that physical ground-disturbance interventions immediately and effectively create alternative foraging habitat. The authors suggest that multiple areas of disturbed-ground, close to the edge of large grassland blocks, can provide a network of nesting and foraging habitats, whilst allowing access to a mixture of feeding opportunities in the surrounding arable farmland. Of course, nobody is suggesting that intensive outdoor pig-rearing is a positive addition to the habitat mix, as it involves nutrient run-off, ammonia leakage into fragile plant-rich heathland, and pelleted feed attracts corvids (which are known to predate eggs).

The effect of creating ploughed or harrowed plots is almost immediate, in terms of prey availability. In more detailed studies of the effectiveness of slightly different ground-disturbance options, the research team found a strong selection preference only one year after the treatments were first implemented. In the longer term, these areas may become increasingly important, if young birds recruit to the local population and seek out these features. The researchers suggest that a bespoke, ground-disturbance agri-environment option might open up new breeding opportunities within semi-natural grasslands that are currently dominated by tall, closed swords.

In England, conservation of dry grasslands and heathlands has tended to focus on the preservation of charismatic plant communities, an approach that may have been too gentle and conservative for other taxa. Whilst this study demonstrates that adding pockets of disturbed ground appears to benefit Stone-curlews, previous studies, conducted by this research team, showed benefits for Woodlark (Hawkes et al. 2019), Eurasian Curlew (Zielonka et al. 2019, summarised in Curlews and foxes in East Anglia), and rare, scarce or threatened dry-grassland invertebrates (Hawkes et al. 2019). Similar disturbance techniques have been shown to potentially benefit other grassland-breeding waders, such as Mountain Plovers (Augustine & Skagen 2014) and Upland Sandpipers (Sandercock et al. 2015) in North America, and Sociable Lapwings in Kazakhstan (Kamp et al. 2009).

Paper

This is a summary of a 2021 paper in Animal Conservation:

Effects of experimental land management on habitat use by Eurasian Stone-curlews. Robert W Hawkes, Jennifer Smart, Andy Brown, Rhys E Green, Helen Jones & Paul M Dolman.

Each summer, farmers, volunteers and conservation staff work together to monitor and protect nesting Stone-curlews on farmland, grasslands and heaths in eastern and southern England. Thanks to all of these people, the number of pairs of Stone-curlew in England is holding steady, at over 300 pairs. Progress was reviewed at a conference in 2017, as you can read in this layman’s report and this technical report. More guidance for landowners can be found here.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton (@GrahamFAppleton) to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on published papers, with the aim of making shorebird science available to a broader audience.

Pingback: Grassland management for Stone-curlew | wadertales – Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog

Reblogged this on Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: WaderTales blogs in 2021 | wadertales

Pingback: A Norfolk Curlew’s summer | wadertales

Pingback: Curlew nest survival | wadertales