More and more trees are being planted in lowland Iceland – and further increases are planned, in part encouraged by the suggestion that this will mitigate for climate change. Forestry is potentially bad news for Whimbrel, Black-tailed Godwit and other waders that breed in open habitats, and which migrate south to Europe and Africa each autumn. Are there ways to accommodate trees while reducing the damage to internationally important populations of waders?

Pressure on Iceland’s breeding waders

Iceland is changing; more people want second homes in the countryside, the road network is being developed to cope with more and more tourists, new infrastructure is needed to distribute electricity, agriculture is becoming more intensive and there is a push to plant lots more trees. The south of the country is seeing the most rapid loss of open spaces, providing opportunities to study how these incursions affect ground-nesting species, particularly breeding waders.

One of the big changes, especially in Southern Iceland, has been the planting of non-native trees, as shelter belts around fields and country cottages and, more significantly, as commercial crops. Iceland has been largely treeless for hundreds of years but climatic amelioration has facilitated rapid forestry development in areas where tree growth was previously limited by harsher environmental conditions. Seeds of some non-native species are blown on the wind for a kilometre or more, to germinate in open land, well beyond the edge of planned forests.

Most of the new forests are in lowland areas, where we also find the most important habitats for many ground-nesting bird populations. Lodgepole pines may be good news for Goldcrest and Crossbills but not for species such as Golden Plover, Dunlin & Redshank. For breeding waders, the most obvious impact of a new forest is direct loss of breeding habitat but trees can have wider effects, by providing cover for predators and breaking up swathes of open land that are used at different stages of the breeding season. Little is currently known about how predators in Iceland use forest plantations but any perceived risks of predator presence and reduced visibility is likely to influence densities of birds in the surrounding area.

Aldís E. Pálsdóttir’s studied changing bird populations in lowland Iceland during her PhD at the University of Iceland, in collaboration with researchers from the University of East Anglia (UK) and the University of Aveiro (Portugal). Among the most concerning of these changes is the rapid expansion of forestry in these open landscapes.

Assessing the potential impacts of trees

In a 2022 paper in the Journal of Applied Ecology, Aldís assesses whether densities of ground-nesting birds are lower in the landscape surrounding plantations and whether these effects vary among plantations with differing characteristics. She and her fellow authors then quantified the potential impact of differing future afforestation scenarios on waders nesting in lowland Iceland.

Forestry currently covers about 2% of Iceland’s land area so the potential for growth is massive. In 2018, the Icelandic government provided additional funding to the Icelandic forest service to increase the number of trees planted, with a goal of enhancing carbon sequestration. As forestry primarily operates through government grants to private landowners, who plant trees within their own land holdings, plantations typically occur as numerous relatively small patches in otherwise open landscapes. These features make Iceland an ideal location in which to quantify the way that plantations affect densities of birds in the surrounding habitats, and to identify afforestation strategies that might reduce impacts on globally important wader populations.

To measure the effects of plantation forests on the abundance and distribution of ground-nesting birds, in particular waders, 161 transect surveys were conducted between May and June 2017. To avoid systematic bias arising from possible “push effects” of corralling birds in front of the surveyor, surveys were conducted along transects that started either at the edge of the plantation, with the observer moving away (79 transects), or started away from the plantation, with the observer walking towards it (82 transects). Please see the paper for the full methodology. The variation in density with distance from plantation was used to estimate the likely changes in bird numbers, resulting from future afforestation plans, and to explore the potential effects of different planting scenarios.

Bird communities change around plantations

On the transects, 3713 individual birds of 30 species were recorded. The nine most common species (excluding gulls, which rarely breed in the focal habitats) were seven waders (Oystercatcher, Golden Plover, Dunlin, Common Snipe, Whimbrel, Black-tailed Godwit & Redshank) and two passerines (Meadow Pipit & Redwing). These species accounted for 88% of all birds recorded.

- Of the seven waders, Snipe was the only one found in significantly higher numbers closer to plantations. Snipe density declined by approximately 50% between the first (0-50 m) and second (50-100 m) distance intervals, suggesting a highly localised positive effect of plantations on Snipe densities.

- Densities of Golden Plover, Whimbrel, Oystercatcher, Dunlin and Black-tailed Godwit all increased significantly with increasing distance from plantations. Dunlin and Oystercatcher showed the largest effect (~15% increase per 50 m), followed by Whimbrel (~12%), Black-tailed Godwit (~7%) and Golden plover (~4%).

- Although Redshank did not show a linear relationship with distance from plantation edges, densities were lowest close to the plantation edge.

- There were more Redwings close to woodland edges but Meadow Pipit showed no change in density with distance from plantations.

Golden Plover, Whimbrel and Snipe were found in lower densities close to the tallest plantations (over 10 m), when compared to younger plantations (tree height 2m to 5m), suggesting that the impact of forests gets more pronounced as the trees grow. Plantation density and diameter had no additional effect on the species that were in lower densities closer to the plantations, implying that the mere presence of plantations induces the observed changes in abundance. See the paper for more details.

The bigger picture

Aldís Pálsdóttir and Harry Ewing walked every step of every transect and made detailed counts of what they saw – data that are invaluable when considering local impacts of plantations – but the paper becomes even more interesting when the authors look at the bigger picture. When plantations are distributed across these open landscapes, in different configurations, what will be the accumulated effects on the numbers of breeding waders? They estimate likely changes in abundance resulting from planting 1000 ha of plantation in different planting scenarios, ranging from a single block to lots of small patches.

- Planting 50 smaller patches of 20 ha, instead of 1000 ha of forest in one large patch, is estimated to double the resulting decline in abundance (because there is more forest edge and hence a bigger effect on more open habitat)

- This effect increases even further as the patches become smaller; in their models, planting 1000 blocks each of 1 ha would have nine times the impact of planting one forest of 1000 ha.

- Proximity of woodland seems to be the driver of local distributions of breeding waders so the authors suggest that the amount of edge (relative to area) should be minimised, to reduce the impact of a plantation – which means making forests as near circular as possible.

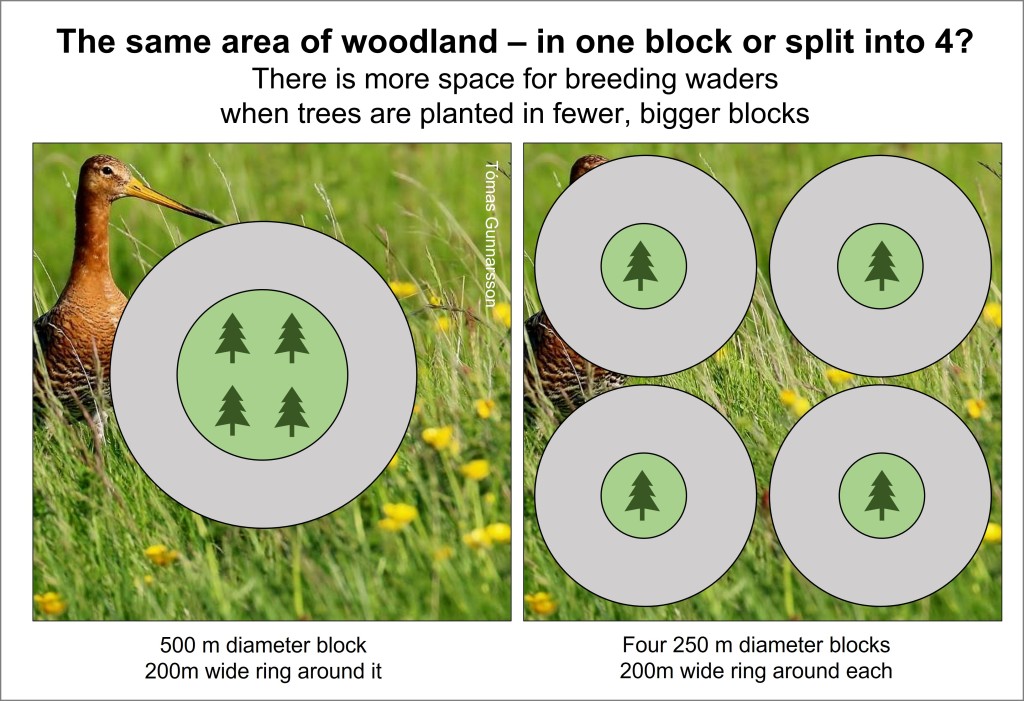

It is clear that fewer larger forestry plots are likely to be less bad than lots of small, local plantations, in terms of the effects on wader populations. The figure below illustrates how much more land is affected when one woodland is replaced by four with the same total area. The grey area (equivalent to a 200 metre annulus) accounts for 88 hectares in the one-patch illustration and 113 hectares for four patches.

An urgent need for action (and inaction!)

Iceland holds large proportions of the global nesting populations of Golden Plover (52%), Whimbrel (40%), Redshank (19%), Dunlin (16%) and Black-tailed godwit (10%) (see Gunnarsson et al 2006) and is home to half or more of Europe’s Dunlin, Golden Plover and Whimbrel. Data in the table alongside have been extracted from Annex 4 of the report, which was discussed at the 12th Standing Committee of AEWA (Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds) in Jan/Feb 2017.

Aldís measured the areas of 76 plantations in her study, using aerial photographs. The total area of woodland was about 2,800 ha and the total amount of semi-natural habitat in the surrounding 200 m was about 3,600 ha. Using the reduced densities that she found on the transects and the direct losses for the plantations themselves, she estimates potential losses of about 3000 breeding waders, just around these 76 forest plots. Extrapolating this figure to the whole of the Southern Lowlands of Iceland, the total losses resulting from all current plantations are likely to already be in the tens of thousands. Worryingly, the densities measured on the transects in this paper (even 700 m from forest edge) were well below those measured (slightly differently) in previous studies of completely open habitat, suggesting that losses may already be significantly higher than estimated in the paper.

A scary statistic in the paper is that “6.3% of the Icelandic lowlands is currently less than 200 m from forest plantations”. Given the incentives to plant lots more trees, this is particularly worrying for species such as Black-tailed Godwits, the vast majority of which breed in these lowland areas (between sea level and 300 metres).

It has been suggested that breeding waders might move elsewhere when impacted by forestry but migratory wader species are typically highly faithful to breeding sites. If birds are not going to move to accommodate trees, then perhaps plantations should be located where bird numbers are naturally low, such as in sparsely or non-vegetated areas, at higher altitudes and on slopes? Planning decisions could usefully be informed by surveys of breeding birds, to identify high-density areas that should be avoided.

The severe impact that planting forests in open landscapes can have on populations of ground-nesting birds emphasises the need for strategic planning of tree-planting schemes. Given Iceland’s statutory commitments to species protection, as a signatory to AEWA and the Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats, and the huge contribution of Iceland to global migratory bird flyways, these are challenges that must be addressed quickly, before we see population-level impacts throughout the European and West African Flyway.

To learn more

The take-home message from this work is clear. Local planning decisions and the ways in which forestry grants are allocated are producing a patchy distribution of plantations across the lowlands of Iceland, and this is bad news for breeding waders.

The paper at the heart of this blog is:

Subarctic afforestation: effects of forest plantations on ground-nesting birds in lowland Iceland. Aldís E. Pálsdóttir ,Jennifer A. Gill, José A. Alves, Snæbjörn Pálsson, Verónica Méndez, Harry Ewing & Tómas G. Gunnarsson. Journal of Applied Ecology.

Other WaderTales blogs that may be of interest:

Forest edges

- The edge effect of forests is discussed in work from Estonia by Triin Kaasiku (see Keep away from the trees). Here she looks at the outcomes of nests at different distances from forest edges.

- Do waders avoid nesting close to trees? This is discussed in Mastering Lapwing Conservation.

- The predator effect lingers long after forests are cleared, according to research described in Trees, predators and breeding waders.

Work by Aldís Pálsdóttir (pictured right)

- The WaderTales blog, Power lines and breeding waders, summarises Effects of overhead power-lines on the density of ground-nesting birds in open sub-arctic habitats.

- Further blogs about wader numbers close to roads and in the vicinity of summer cottages will be added when papers are published.

Changing agricultural systems in Iceland (work by Lilja Jóhannesdóttir)

- Do Iceland’s farmers care about wader conservation? At a time of agricultural expansion, are farmers prepared to leave space for breeding waders?

- Farming for waders in Iceland investigates densities of breeding waders along the gradient of agricultural intensification associated with farming activities.

- Designing wader landscapes investigates whether breeding densities of waders can be maintained, as farming expands and intensification increases.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton (@GrahamFAppleton) to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on published papers, with the aim of making shorebird science available to a broader audience.

Pingback: Power-lines and breeding waders | wadertales

Reblogged this on Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: January to June 2022 | wadertales

Pingback: A Whimbrel’s year | wadertales

Pingback: UK waders: “Into the Red” | wadertales

Pingback: Wales: a special place for waders | wadertales

Pingback: WaderTales blogs in 2022 | wadertales