Decades of drainage and agricultural intensification have caused huge declines in numbers of breeding waders in the lowland wet-grasslands of Western Europe. Although we were already well aware of these problems by 1995, and farmland prescriptions have been used to try to arrest the declines since then, we have still lost nearly half of Britain’s breeding Lapwing in the last twenty years. Even on nature reserves and in sympathetically-managed wet-grassland, it has proved hard to boost the number of chicks produced. Why is this and what else is there that can be done?

Decades of drainage and agricultural intensification have caused huge declines in numbers of breeding waders in the lowland wet-grasslands of Western Europe. Although we were already well aware of these problems by 1995, and farmland prescriptions have been used to try to arrest the declines since then, we have still lost nearly half of Britain’s breeding Lapwing in the last twenty years. Even on nature reserves and in sympathetically-managed wet-grassland, it has proved hard to boost the number of chicks produced. Why is this and what else is there that can be done?

This is a summary of a presentation by Professor Jennifer Gill of the University of East Anglia and Dr Jen Smart of RSPB, delivered at the BOU’s Grassland Workshop (IOC Vancouver, 2018).

This is a summary of a presentation by Professor Jennifer Gill of the University of East Anglia and Dr Jen Smart of RSPB, delivered at the BOU’s Grassland Workshop (IOC Vancouver, 2018).

There are five key techniques in the tool-kit used by conservationists trying to support breeding waders:

- Make the site attractive to waders

- Manage predator numbers, particularly through lethal control

- Manage habitat structure to make alternative prey available

- Exclude predators, either permanently or temporarily

- Invest in head-starting chicks, to boost productivity

Size of the problem

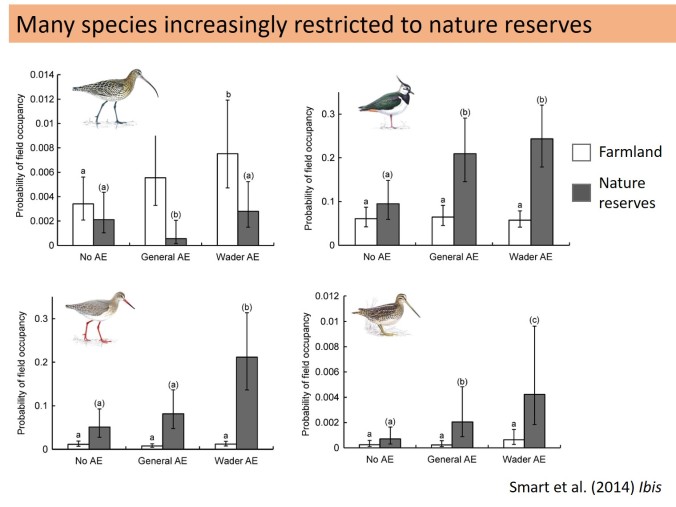

The decline in wader numbers in England has been happening for a very long time. In just the period 1995-2016, Lapwing numbers have fallen by a further 26% and Redshank numbers by 39%, according to Bird Trends, produced by BTO & JNCC. Within the English lowlands there has been a dramatic contraction into nature reserves, especially in the east of England.

The decline in wader numbers in England has been happening for a very long time. In just the period 1995-2016, Lapwing numbers have fallen by a further 26% and Redshank numbers by 39%, according to Bird Trends, produced by BTO & JNCC. Within the English lowlands there has been a dramatic contraction into nature reserves, especially in the east of England.

The Breeding Waders in Wet Meadows survey showed that fields that are within nature reserves are much more likely to be occupied than other fields in wet grassland, particularly those that are included in wader-specific agri-environment schemes. The study is published in Ibis by Jen Smart et al.

Attracting breeding waders

Creating shallow ditches. Mike Page/RSPB

Reserve managers and sympathetic landowners have become very good at creating the sort of habitats that attract breeding Lapwings. Autumn and winter grazing can be manipulated to produce short swards, whilst adding in shallow pools and foot-drains (linear features running through fields) increases feeding opportunities for chicks. See Restoration of wet features for breeding waders on lowland grassland

The RSPB has invested heavily in time and equipment to deliver these lowland west grasslands, on their own land, on other nature reserves and on commercial farmland. By working with Natural England, they have helped to shape agri-environment schemes that can be used to deliver payments to farmers who are well-placed to create habitat that suits breeding waders.

In the east of England, there are now more than 3000 hectares of this attractive, well-managed wet grassland habitat, designed to be just right for species such as Lapwing. The graph alongside, drawn using RSPB data, shows the number of pairs of Lapwing (green), Redshank (red) and other waders (Oystercatcher, Avocet & Snipe: blue) in Berney Marshes RSPB reserve in eastern England for the period 1986 to 2016. There were early successes, as new areas were purchased and transformed, but growth in wader populations has not been sustained, despite ongoing improvements in land management. What is preventing further recovery?

In the east of England, there are now more than 3000 hectares of this attractive, well-managed wet grassland habitat, designed to be just right for species such as Lapwing. The graph alongside, drawn using RSPB data, shows the number of pairs of Lapwing (green), Redshank (red) and other waders (Oystercatcher, Avocet & Snipe: blue) in Berney Marshes RSPB reserve in eastern England for the period 1986 to 2016. There were early successes, as new areas were purchased and transformed, but growth in wader populations has not been sustained, despite ongoing improvements in land management. What is preventing further recovery?

Demographic processes

In a paper in the Journal of Ornithology, Maya Roodbergen et al used demographic data collated across Europe to show that there had been long-term declines in nest survival and increases in nest predation rates in lowland wader species. One of the main focuses of management action at Berney Marshes is to maximise Lapwing productivity but nesting success is still below 0.6 chicks per pair in most years (see graph), which is the minimum estimated productivity for population stability (Macdonald & Bolton). Not enough chicks are being hatched, with the vast majority of egg losses being associated with fox activity.

In a paper in the Journal of Ornithology, Maya Roodbergen et al used demographic data collated across Europe to show that there had been long-term declines in nest survival and increases in nest predation rates in lowland wader species. One of the main focuses of management action at Berney Marshes is to maximise Lapwing productivity but nesting success is still below 0.6 chicks per pair in most years (see graph), which is the minimum estimated productivity for population stability (Macdonald & Bolton). Not enough chicks are being hatched, with the vast majority of egg losses being associated with fox activity.

Controlling foxes

The obvious solution for breeding waders must surely be to shoot foxes? It’s not that simple. In a multi-year, replicated experiment to assess the impact of controlling foxes and crows, RSPB scientists showed that there were no clear improvements in wader nesting success; effectiveness is very much site-specific. Much may well depend on how much fox control there is in the surrounding area.

If fox impacts cannot be reduced sufficiently through lethal control, perhaps it is possible to reduce their effects on waders by understanding the ways in which foxes forage and to adapt the habitat appropriately? Work by Becky Laidlaw and others has shown that Lapwing nest predation rates are lower close to tall vegetation and in areas with complex wet features. However, Becky has also shown that management to create these features, even in areas of high wader density and effective predator mobbing, is only likely to achieve small reductions in nest predation. There is a WaderTales blog about this: Can habitat management rescue Lapwing populations?

If fox impacts cannot be reduced sufficiently through lethal control, perhaps it is possible to reduce their effects on waders by understanding the ways in which foxes forage and to adapt the habitat appropriately? Work by Becky Laidlaw and others has shown that Lapwing nest predation rates are lower close to tall vegetation and in areas with complex wet features. However, Becky has also shown that management to create these features, even in areas of high wader density and effective predator mobbing, is only likely to achieve small reductions in nest predation. There is a WaderTales blog about this: Can habitat management rescue Lapwing populations?

Excluding foxes

One solution to the fox problem that does work is to exclude foxes (and badgers) from an area, by using electric fences. See paper by Lucy Malpas (now Lucy Mason). Fences may be deployed at different scales; just around individual nests, temporarily (around individual fields) or permanently (around larger areas).

One solution to the fox problem that does work is to exclude foxes (and badgers) from an area, by using electric fences. See paper by Lucy Malpas (now Lucy Mason). Fences may be deployed at different scales; just around individual nests, temporarily (around individual fields) or permanently (around larger areas).

- Nest-scale may be most appropriate for species such as Curlew, which have large territories and do not nest colonially. Finding nests is time consuming but relatively small lengths of fence could potentially be erected during the incubation period.

- Whole-site protection will suit semi-colonial species such as Lapwing. Although expensive to install, permanent fences can require relatively little maintenance and can potentially be powered by mains electricity. One disadvantage may be that the presence of large numbers of chicks can attract avian predators, such as birds of prey, which are themselves conservation priorities and hence difficult to manage.

Field-scale fences usually rely on batteries, which need to be checked and changed, and fences need maintenance, as the grass grows and can short out the bottom strands. However, deployment at the field-level allows for dynamic use within a farming landscape and in accordance with agri-environment schemes. New research by RSPB and the University of East Anglia aims to see if fences need only to be deployed for relatively short periods. If pairs nest synchronously then groups of birds may be able to maintain the ‘fence-effect’ by mobbing predators, when a temporary fence is removed.

Field-scale fences usually rely on batteries, which need to be checked and changed, and fences need maintenance, as the grass grows and can short out the bottom strands. However, deployment at the field-level allows for dynamic use within a farming landscape and in accordance with agri-environment schemes. New research by RSPB and the University of East Anglia aims to see if fences need only to be deployed for relatively short periods. If pairs nest synchronously then groups of birds may be able to maintain the ‘fence-effect’ by mobbing predators, when a temporary fence is removed.

RSPB has produced The Predator Exclusion Fence Manual. Click on the title for a link.

Head-starting

Although it might be possible to improve the habitat that is available for breeding waders and to reduce predation pressure, it is sometimes too late to boost numbers – simply because populations have shrunk to too low a level. At this point, head-starting (rearing chicks from eggs) may be appropriate. This blog celebrates the success of the first year of a joint initiative by RSPB and WWT (Project Godwit) to increase the local population of Black-tailed Godwits in the East Anglian fens: Head-starting Success.

Although it might be possible to improve the habitat that is available for breeding waders and to reduce predation pressure, it is sometimes too late to boost numbers – simply because populations have shrunk to too low a level. At this point, head-starting (rearing chicks from eggs) may be appropriate. This blog celebrates the success of the first year of a joint initiative by RSPB and WWT (Project Godwit) to increase the local population of Black-tailed Godwits in the East Anglian fens: Head-starting Success.

In conclusion

In trying to boost breeding wader populations, land-managers and conservationists have developed techniques to increase site attractiveness and reduce predator impacts, through management, control and exclusion. The tools that are used will depend upon species, budget and conservation priorities.

This work was presented by Jennifer Gill & Jen Smart at a BOU symposium on the Conservation of Grassland Birds, in Vancouver, August 2018.

WaderTales blogs about Lapwings and Redshanks

WaderTales blogs about Lapwings and Redshanks

The work of RSPB and University of East Anglia scientists features strongly in these blogs, which focus on support for breeding wader populations in lowland wet grassland and on coastal saltings.

- A helping hand for Lapwings investigates ways of keeping predators and wader chicks apart.

- How well do Lapwings and Redshanks grow? reports on a Wader Study paper that shows that there is plenty of food available on wet grassland managed for waders.

- Big-foot and the Redshank nest investigates appropriate cattle stocking levels for successful Redshank breeding.

- Can habitat management rescue Lapwing populations? Might the right mix of pools and verges with long grass provide a big enough uplift in nest success rates?

- Mastering Lapwing conservation focuses on two MSc projects that investigated actual and perceived risks of predation in Lapwings.

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton (@grahamfappleton), who has studied waders for over 40 years and is currently involved in wader research in the UK and in Iceland. He was Director of Communications at The British Trust for Ornithology until 2013 and is now a freelance writer and broadcaster.

Another excellent blog. Predator control is an emotive subject and I am glad to highlight it, but you have not mentioned corvids. I watched crows searching for lapwing and avocet nests this spring. Is there scientific evidence that corvid control improves the reproductive success of waders? It will be needed if we are to go down that route.

LikeLike

The studies I have looked at all use a combination of fox and corvid control.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: Flyway from Ireland to Iceland | wadertales

Pingback: A helping hand for Lapwings | wadertales

Pingback: WaderTales blogs in 2018 | wadertales

Pingback: Managing water for waders | wadertales

Pingback: Nine red-listed UK waders | wadertales

Pingback: Cycling for waders | wadertales

Pingback: The First Five Years | wadertales

Pingback: England’s Black-tailed Godwits | wadertales

Pingback: Eleven waders on UK Red List | wadertales

Pingback: Keep away from the trees | wadertales

Pingback: UK waders: “Into the Red” | wadertales

Pingback: Wales: a special place for waders | wadertales

Pingback: Curlew nest survival | wadertales