Across the world, agriculture is one of the primary threats to biodiversity, as we tear up natural environments to create more space to feed an ever-growing and increasingly meat-hungry human population. Agricultural land can, however, also provide key resources for many species whose behaviours align with the rhythms of the farming year.

In Iceland, farming areas support large and important populations of several wader species, including 75% of Europe’s Whimbrel and over half of Europe’s Dunlin. As the country welcomes more tourists and expands the range of crops grown for food and fuel, what might be the implications for iconic species such as Whimbrel, Dunlin and Black-tailed Godwit?

This paper by Lilja Jóhannesdóttir, of the University of Iceland, and colleagues there and at the universities of Aveiro (Portugal) and East Anglia (UK), investigates the use of farmland by waders living in a semi-natural landscape.

Paper details: Use of agricultural land by breeding waders in low intensity farming landscapes Lilja Jóhannesdóttir, José A. Alves, Jennifer A. Gill, & Tómas Grétar Gunnarsson Animal Conservation. doi:10.1111/acv.12390

A dynamic landscape

In Iceland, volcanic activity poses serious short-term threats to agriculture, especially in areas close to the mid-Atlantic ridge, which runs through the island from south-west to north-east. Threats from volcanoes include ash-fall, lava, flooding of glacial rivers and earthquakes but, on the plus side, nutritional inputs from volcanoes have beneficial effects on soil fertility in these central areas. Over time, and with the assistance of wind and water, many of these nutrients collect in the lowlands of the country – the areas that now form the main agricultural areas, especially in the warmer south.

In Iceland, volcanic activity poses serious short-term threats to agriculture, especially in areas close to the mid-Atlantic ridge, which runs through the island from south-west to north-east. Threats from volcanoes include ash-fall, lava, flooding of glacial rivers and earthquakes but, on the plus side, nutritional inputs from volcanoes have beneficial effects on soil fertility in these central areas. Over time, and with the assistance of wind and water, many of these nutrients collect in the lowlands of the country – the areas that now form the main agricultural areas, especially in the warmer south.

The distribution of breeding waders varies across lowland Iceland. A survey carried out between 2001 and 2003 showed that wader densities were greater in areas of the country that had been subject to higher rates of volcanic ash deposition with, for instance, three times as many waders in the south as in the west. See How volcanic eruptions help waders. As was shown in the paper at the heart of that blog, the nutrient signal associated with ash-fall breaks down in farmland. Here, perhaps as a consequence of the application of natural and artificial fertilisers over decades or even centuries, there is no association between ash-fall and wader density. Across the whole country, irrespective of the proximity of volcanoes, nutrient-rich agricultural land attracts waders – but which wader species and across which farmland habitats?

Waders and agriculture

In a previous paper, Lilja Jóhannesdóttir showed that over 90% of Icelandic farmers think it is important or very important to have rich birdlife on their estates, but that farmers also expect to increase the area of farmed land in the coming years. There’s more about this in the WaderTales blog: Do Iceland’s farmers care about wader conservation? It is important to understand the ways that waders currently use farmland, in the hope that nesting waders can continue to be accommodated within the future farming landscape of Iceland.

Perhaps Oystercatchers think that the fields have been ploughed especially for them?

Agriculture in Iceland is still relatively low in intensity and extent, and internationally important populations of several breeding bird species are abundant in farmed regions. Only about 2% of land is cultivated (about 7% of lowland areas), of which about 85% is hayfields (grass fields managed to produce crops of grass for storage as winter feed) and 15% consists of arable fields (mostly barley). This is similar to areas such as Norway, northern Canada and northern and western areas of the British Isles but contrasts sharply with the US and many countries in the EU which, on average, have 20% or more of their land under cultivation.

In these high-latitude landscapes, agricultural land can potentially provide resources that help to support wader species. To address these issues, Lilja conducted surveys of bird abundance on 64 farms in northern, western and southern areas of Iceland that vary in underlying soil productivity, and quantified:

- Levels of breeding bird use of farmed land managed at three differing intensities, ranging from cultivated fields to semi-natural land

- Changes in patterns of bird use of farmed land throughout the breeding season.

Farm survey

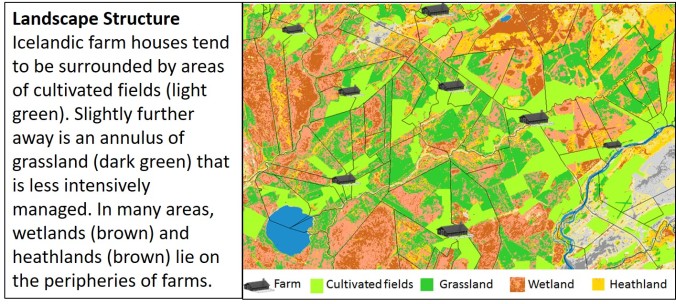

In Iceland, there are still large patches of natural or semi-natural habitats; they surround the hay-fields and arable fields that are at the heart of many farms. This arrangement creates gradients of agricultural intensity from the farm into the surrounding natural land, tapering from intensive management to moderate and light management.

The three intensity levels within Icelandic farmland can be roughly described as follows:

- Intensive: Hayfields (85%) and arable fields (15%) fields. Most hayfields are mown twice per year and ploughed and reseeded every few years.

- Moderate: Old hayfields that are rarely or never mown but are used for grazing, or fertilized grasslands used for livestock grazing.

- Light: Semi-natural or natural areas under low intensity grazing, usually by sheep or horses, or with no agricultural influence, ranging from sparsely vegetated habitats to habitats with abundant vegetation (where grasses and bushes dominate the vegetation) and with a broad wetness gradient.

Fields corresponding to these three categories were surveyed on the 64 farms, firstly during the egg-laying and incubation period and then later, to coincided with chick rearing.

Gradient of management from intensive (left) to wet semi-natural (right)

Where were the waders?

Large numbers of waders were encountered in all transects in all parts of Iceland, with Black-tailed Godwit and Redshank contributing most records. There were also important numbers of Oystercatcher, Golden Plover, Dunlin, Snipe and Whimbrel. Overall, wader densities on farms did not vary significantly between regions or between early and late visits but there were some subtle differences:

Large numbers of waders were encountered in all transects in all parts of Iceland, with Black-tailed Godwit and Redshank contributing most records. There were also important numbers of Oystercatcher, Golden Plover, Dunlin, Snipe and Whimbrel. Overall, wader densities on farms did not vary significantly between regions or between early and late visits but there were some subtle differences:

- Wader density varied significantly along the management gradient, with lower densities tending to occur in more intensively managed areas, particularly in the early (nest-laying and incubation) season.

- Intensively managed fields in the west (where underlying soil productivity is lower) had higher densities of waders than in the north and south of the country.

- There were seasonal declines in wader density on all three management types in the south, but seasonal increases on intensive and moderate management in the west and in fields under moderate management in the north.

- There were some differences between species in these patterns (more details in paper).

One of the interesting differences in the west was the redistribution of Redshank as the season progressed. There were three times as many pairs of Redshank in cultivated land during the chick-rearing period than during incubation, suggesting that adults may be moving broods into cultivated land. Resources for chicks may well be relatively more abundant or accessible in these areas, given the relatively low levels of nutrients in areas that are a long way from the active volcano belt. There’s also a suggestion that drainage ditches around cultivated fields in the west may provide important resources for Snipe.

One of the interesting differences in the west was the redistribution of Redshank as the season progressed. There were three times as many pairs of Redshank in cultivated land during the chick-rearing period than during incubation, suggesting that adults may be moving broods into cultivated land. Resources for chicks may well be relatively more abundant or accessible in these areas, given the relatively low levels of nutrients in areas that are a long way from the active volcano belt. There’s also a suggestion that drainage ditches around cultivated fields in the west may provide important resources for Snipe.

What about the future?

Wader densities during the early (red) and later (blue) part of the breeding season (Modified from the paper in Journal of Animal Conservation)

Although the density of birds in Iceland’s agricultural landscapes tends to be higher in lightly managed than intensively managed agricultural land, densities in the areas under the most intense agricultural management are still high, suggesting that agricultural habitats provide important resources within these landscapes (see figure alongside). These density estimates (between 100 and 200 waders/km2) are typically much higher than those recorded in other countries in which these species breed.

Farmers in Iceland expect to expand their cultivated land in the coming years in response to increasing demand for agricultural production (Do Iceland’s farmers care about wader conservation?), and evidence from other countries throughout the world has shown how rapidly biodiversity can be lost in response to agricultural expansion and intensification. Protecting these landscapes from further development is crucial to the species that they support.

The authors suggest ways in which farming practises might change wader distributions in Iceland. Here are a few of the interesting points that they make:

- When wader-rich semi-natural land is replaced by arable farming and intensively-managed hayfields, this is likely to reduce overall wader densities.

- Losing wet features, which provide insect food for waders, may well have impacts for chick growth. Here’s a WaderTales blog that discusses the importance of wet features to Lapwings in the UK.

- In other countries, early grass mowing is a direct threat to nests and chicks. Clutch and brood losses are already being observed in Iceland and, with warmer springs encouraging earlier grass growth, this could become more of a problem.

- The conversion of less-intensively managed areas into farmland is likely to have most effect on Dunlin, Black-tailed Godwit and Whimbrel, which tend to occur in their highest densities in the least intensively managed lowland areas.

It is estimated that between 4 and 5 million waders leave Iceland each autumn, for Europe, Africa and the South Pacific (Red-necked Phalarope). Iceland’s farmland supports many of these birds and this study highlights the need to protect them from the agricultural developments that have led to widespread wader losses throughout most of the world.

It is estimated that between 4 and 5 million waders leave Iceland each autumn, for Europe, Africa and the South Pacific (Red-necked Phalarope). Iceland’s farmland supports many of these birds and this study highlights the need to protect them from the agricultural developments that have led to widespread wader losses throughout most of the world.

You can read the paper here

Use of agricultural land by breeding waders in low-intensity farming landscapes Lilja Jóhannesdóttir, José A. Alves, Jennifer A. Gill, & Tómas Grétar Gunnarsson. Animal Conservation. doi:10.1111/acv.12390

WaderTales blogs are written by Graham Appleton, to celebrate waders and wader research. Many of the articles are based on previously published papers, with the aim of making wader science available to a broader audience.

Pingback: WaderTales blogs in 2017 | wadertales

Great read all. Some facts to consider if we undertake upland farmland and marginal fields survey work. Especially for wader work.

LikeLike

Pingback: Do Iceland’s farmers care about wader conservation? | wadertales

Reblogged this on Wolf's Birding and Bonsai Blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: Designing wader landscapes | wadertales

Pingback: Where to nest? | wadertales

Pingback: Power-lines and breeding waders | wadertales

Pingback: Iceland’s waders need a strategic forestry plan | wadertales